Title

Subhead

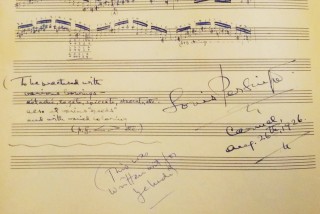

Detail of Persinger's “A Daily Study in Thirds”

During my studies at Juilliard with Dorothy DeLay ('42, violin; faculty 1948–2002), there was a name she would mention with a tone of reverence, especially when we talked about the violin works of Eugène Ysaÿe (1958–1931). That name was Louis Persinger (violin faculty 1930–66). Persinger was already familiar to me as an important American disciple of Ysaÿe, and as the legendary pedagogue whose guidance was decisive in the technical and artistic development of Yehudi Menuhin ('26, music theory) and Ruggiero Ricci (faculty 1975–79), among many others. Fortune led me on, and as my studies of Ysaÿe became more involved, so did my familiarity with the materials that Persinger had donated to Juilliard.

Body

Persinger (1887–1966), the son of a railway signalman, was born in Colorado and started playing music in public by the age of 12. He later studied in Leipzig, where he won the praise of Arthur Nikisch, and then continued his studies with Ysaÿe in Brussels and Jacques Thibaud in France. Returning to the United States to pursue a career as a soloist, conductor, chamber musician, and, most famously, pedagogue, Persinger eventually succeeded Leopold Auer (faculty 1926–30) at Juilliard, teaching here from 1930 until his death, in 1966. A wonderful pianist as well as violinist, Persinger played the piano on several of Menuhin's and Ricci's recordings and performed his own 75th-birthday recital, in 1962, at Juilliard, with half the program on piano and half on violin. The Louis Persinger Music Collection in Juilliard's Peter Jay Sharp Special Collections includes Persinger's papers, manuscripts, and a large library of annotated scores, among them three of Ysaÿe's autograph manuscripts for Solo Sonatas Nos. 2, 3, and 6, which are available for viewing at the Juilliard Manuscript Collection website. And in helping process materials in the Persinger Collection, my eyes came across something that no violinist would be able to ignore—manuscripts of original violin exercises by Persinger.

These working manuscripts, created between 1926 and 1930, deal with a range of technical issues that any serious violinist would have to face in tackling advanced repertory. There are exercises in thirds, octaves, large chords, and of course, seemingly innocuous passages with remarks for fingerings, bowings, articulations, and rhythms, turning them into tightrope walks.

One 1926 manuscript, “A Daily Study in Thirds,” bears the words “This was written out for Yehudi.” Another, from 1928, features triple- and quadruple-stop chords and says “For Ruggiero Ricci.” And then there is a set of more comprehensive exercises collected under the ominous-sounding titles “Musical Drudgery” and “More Musical Drudgery!”

There are hints that Persinger had considered publishing these exercises. Among his papers is an annotated, typewritten page with the title “Musical drudgery,” which reads like a possible preface to these exercises. In that text, Persinger wrote, “Certain ones of these exercises are by no means easy, I know, and a few are quite tricky and awkward.” From the tongue-in-cheek title to the almost-apologetic statement about their difficulty, the unique humor is a foil to the strict yet imaginative discipline the author lays out.

Menuhin, who frequently and publicly praised and thanked Persinger, recalled an episode that reflects this playful humor. Reflecting on his early studies with Persinger, Menuhin wrote in his second memoir, Unfinished Journey: Twenty Years Later, “To make practice tolerable, [Persinger] improvised exercises for me, on one occasion drawing scales in thirds to resemble toy trains moving across hill and dale. I would not be surprised if this design had been inspired by a Bach autograph, but it bore witness to the unfortunate conviction I held that exercising was child's play and therefore inimical to my quest for reality.” It's not entirely clear when this episode happened, but a credible hypothesis could be that the exercises in thirds marked “for Yehudi” in the Persinger Collection may be the very manuscript Menuhin remembered so well.