Title

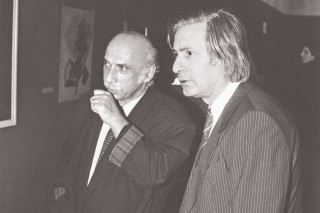

Alfred Schnittke (right) with Giya Kancheli in an undated photograph by Kancheli’s wife.

(Photo by Lula Kancheli)This year’s Focus! festival, the 30th, commemorates what would have been the 80th birthday of Alfred Schnittke, who died in 1998 at age 64 after suffering several strokes. Although many of us like to steer clear of applying the term “great” to living or recent composers, I am disposed to apply it to him because of his deep musicality, superb compositional technique, and unconventional imagination.

The work of Russian composer Alfred Schnittke, who died in 1998, is on display at this year’s Focus! festival. Multiple concerts featuring work by Schnittke and some of his colleagues will be performed from January 24 to 31, and there will be a panel discussion on January 28. Pictured, from top: Arvo Pärt and Alfred Schnittke in about 1980, photographed by Pärt’s wife; Valentin Silvestrov; and Sofia Gubaidulina. (Photos courtesy of Nora Pärt, Roberto Masotti and Japan Art Association/The Sankei Shimbun)

Body

I first encountered Schnittke’s music in 1979, when Continuum—the professional ensemble that I co-direct with Cheryl Seltzer—was planning a program of Soviet avant-garde composers, which took place at Alice Tully Hall in 1980. The first such public concert in this country (as far as we know), it garnered a review in Newsweek that helped launch those composers in the U.S. The following year, we gave an all-Schnittke program—also the first in the U.S., I believe—that drew a large range of reviews. Unfortunately, very negative comments by a New York Times critic played into the hands of Schnittke’s enemies in Moscow, where The Times was considered an official organ of the U.S. government. That critic’s suggestion that there was no reason why anyone would listen to such music was just what the reactionary faction in the U.S.S.R. had been saying in order to obstruct the activities of Schnittke and other unconventional composers. I was therefore doubly distressed when, some years later, that same critic told me that he had completely changed his mind and decided that Schnittke was one of the greatest living composers. His reversal came far too late for Schnittke, who continued to suffer from the hostility of the Union of Composers, which controlled its members’ professional lives.

Schnittke’s response to seeing that initial review, however, revealed his extraordinary resilience. He told me he hoped people would like his music, but didn’t mind if they hated it; he only disliked noncommittal or bored responses. Then he added that when he listened to music by an unfamiliar composer, at first he heard what he wanted to hear and only after more exposure did he start hearing what the composer heard. It was an excellent lesson. As for his music, generalizations are difficult because he was not wedded to a single style. Indeed, he is known as the “inventor” of polystylistic music, in which extraordinarily different idioms coexist, complement, and contrast with one another within a single piece. Yet no matter what its surface, his music is always marked by a singular intensity and dynamicism, and it is composed with consummate technique.

I always felt that Schnittke and I might have become good friends if we had had more time together, but all his attempts to travel abroad were blocked by Tikhon Khrennikov, the dictator of the Union of Composers, who was implacably hostile to Schnittke. I did not get to Moscow while he still lived there, or to Hamburg after he and his family emigrated in 1990, as the U.S.S.R. was collapsing. We met a few times in New York in the 1990s, however. Once, at a small dinner party at the home of his cousin, he explained to me that, unlike the other Russians in the room, he could not drink because of his recent stroke. Although his speech was fine, he was still having trouble writing. Efforts to teach him how to compose with a computer got nowhere because his pencil was part of him. That he managed to produce so much more music is a tribute to his powerful will. Our final encounter took place at the New York Philharmonic’s world premiere of his Seventh Symphony in 1994, by which time he had suffered more strokes. When he came to the stage to acknowledge the ovation, he looked ashen and exhausted. When we met backstage, however, the force of his handshake astounded me.

Devoting a Focus! festival to Schnittke has been on my mind since I saw the announcement of a commemoration of his 75th year at London’s Southbank Centre, a grand event that also included symposia and films with his scores. A festival at Juilliard, however, has special significance because we own many of Schnittke’s manuscripts. To give the students broad experience in the festival, it made sense to include compositions by Schnittke’s closest friends and associates. Discussions with people who knew him well—among them musicologist Laurel Fay; cellist and biographer Alexander Ivashkin; and Hans-Ulrich Duffek, the director of Hans Sikorski, the renowned publisher of Soviet-era composers—narrowed the field of other composers to three superb colleagues, Sofia Gubaidulina, Arvo Pärt, and Giya Kancheli. Having known all of those composers for years, I extended a planned trip to Europe so that I could see Gubaidulina and Irina Schnittke, the composer’s widow, in Hamburg, and Kancheli in Antwerp, Belgium. Unable to go to Estonia to visit Pärt, I communicated with him by e-mail.

All three composers spoke of sharing a deep spirituality with Schnittke, recalling how he gave them the strength to take artistic risks in the face of pressure from the authorities or from colleagues who had recently learned of developments in Western Europe and adopted a dogmatically modernist persuasion. Pärt has credited Schnittke with giving him the crucial advice not to hole up in his studio with his sketches but put his ideas into musical form, and that counsel led him to the style for which he is now famous. Kancheli told me that while most of the new, Moscow-centered circle of experimental composers, inspired by their new knowledge of European avant-gardism, came very close to the borderline between conventional and unconventional, only two people actually crossed it—Pärt and Schnittke. (Kancheli included the new modernism among the conventions that had become difficult to breach.) Later Gubaidulina and Kancheli would join them in that lonely world of noncomformity. For these three composers, Schnittke’s uncompromising dedication to his own vision was a real inspiration. After the programs were nearly complete, various consultations and a message from Irina Schnittke confirmed my hunch that Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov should also be included in the festival.

This year’s Focus! will open on January 24 with the New Juilliard Ensemble giving the world premiere of a completely new version of Pärt’s La Sindone (2005), which will be complete just as this edition of The Journal appears. The program also includes Kancheli’s Midday Prayers, for clarinet, boy soprano, and chamber orchestra; and Schnittke’s Symphony No. 4, both of which were given their U.S. premieres in previous Focus! festivals. The clarinetist for the Kancheli will be master’s student Yeon-Hyung Lim; the boy soprano will be provided by St. Thomas Church. Singers for Schnittke’s symphony are fourth-year soprano Laura LeVoir, third-year alto Hannah McDermott, and master’s students William Goforth (tenor) and Joseph Eletto (baritone). The series closes on January 31 with Anne Manson conducting the Juilliard Orchestra in Gubaidulina’s Fairy Tale Poem; Kancheli’s And farewell goes out sighing ... for countertenor, violin, and orchestra; and Schnittke’s Symphony No. 8. The soloists for Kancheli’s piece are countertenor John Holiday, a second-year Artist Diploma candidate, and violinist Ken Hamao, a D.M.A. candidate. In addition to the orchestral concerts, there will be four chamber concerts (January 27-30). At 7 p.m. on January 28 a panel discussion with Laurel Fay, pianist Vladimir Feltsman, Hans-Ulrich Duffek, and retired Foreign Service officer Eleanor Sutter will precede the concert.