Title

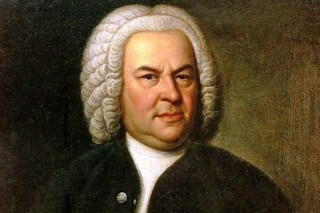

Johann Sebastian Bach (Wikimedia Commons/Elias Gottlob Haussmann)

For Historical Performance students, our upcoming performances of J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew and St. John Passions present two unique and wonderful opportunities to tackle some of the most monumental music in the history of Western music. The St. John, which will be performed in New York and New Haven in April, will be Juilliard’s fourth collaboration with the Yale Schola Cantorum, the flagship choir of the Yale Institute of Sacred Music under the direction of Masaaki Suzuki. The St. Matthew will be performed in mid-March by Juilliard415, Juilliard singers, and the choir of Trinity Wall Street all under the direction of Juilliard faculty member Gary Thor Wedow. Performances will be given at the Juilliard in Aiken (S.C.) festival, at the acoustically exquisite Spivey Hall in Morrow, Ga., and at Alice Tully Hall.

Body

The Passions are oratorios that present the Biblical story of the suffering and death of Jesus as large-scale musical productions. Recently, faculty member Christoph Wolff, who’s teaching a course this semester on both of Bach’s surviving Passions, chatted about these seminal works with The Journal. The Passion oratorios, which were performed at the afternoon service on Good Friday, were “the absolute high point in the musical life in Leipzig, and for Bach as a performer-composer,” Wolff said, adding that the St. Matthew in particular was “a work without any precedent in his or anyone else’s compositional output. It was a daring attempt to produce a big work using such large-scale forces in a single performance.”

To get a sense of just how unprecedented the Passions were, consider that Bach’s immediate predecessor as music director of the St. Thomas Choir in Leipzig, Johann Kuhnau, who held the position from 1701 to 1722, was the first composer to present a Passion oratorio at the church, in 1721. In fact, Lutheran Germany didn’t have a very long tradition of Passion oratorio performances, Wolff said, noting that the tradition began in Hamburg in 1712. “Before that, there was a long-standing medieval tradition of liturgical performances presented in a much simpler way rather than the sort of elaborate presentation that essentially amounts to a sacred opera,” Wolff added. While there had been only one Passion in Leipzig, Bach had studied the music of Georg Philipp Telemann and Reinhard Keiser, both of whom had also written Passions, but Bach “always wanted to go his own way and, if possible, top what been done before,” Wolff said.

Beyond the genesis of the Passions, another key event plays into their importance today. In 1829, the 19-year-old Felix Mendelssohn conducted what is generally considered to be the first “modern” revival of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, which had fallen into obscurity shortly after its initial performances in the 1720s. Not only did it create a lot of excitement because Mendelssohn was so young, but also because at the time it wasn’t common (unlike today) to revive music that was so old. A lot of our contemporary performance practice, especially as it pertains to Bach’s music, can be traced back to this event, Wolff said. “He gave the performance in a concert hall to an audience for the purpose of delighting in the music. It was the kind of piece that was originally set as a piece of church music, so it had a much larger, universal appeal that was then taken out of the realm of the church,” he added.

Since certain instruments that Bach called for were no longer available—the oboe d’amore, the oboe da caccia, and the viola da gamba—Mendelssohn “had to find appropriate replacements,” Wolff said. He gave the role of the alto oboe to the clarinets, “which made a difference in the quality of sound and helped to make the work appeal to a contemporary audience,” he added. “I think they would have been more irritated by the kind of period-instrument practice we would find attractive today.” Since audiences of the day were used to contemporary music, in presenting anything else “you had to make it fit the modern ear. Today we have a much broader perspective on the history of music and the history of musical performance.”

So is it historically inaccurate to present the Passions on multiple days in the same season, some during Lent and some after? Not as much so as one might think, Wolff said. Bach mounted just one Passion annually, alternating between the two principal churches in Leipzig. But in Hamburg, a much larger city, where Telemann and C.P.E. Bach were serving as music directors, the Passions were performed five times in five churches, Wolff explained. Given that context, in a city as large as New York, he said, “you could have 20 performances and still claim that this is historic practice!”

For those who don’t have the wherewithal to attend all five of Juilliard’s performances (in four states), Wolff offered some key traits to listen for, noting that the Passion narrative is so rich that it “provides lots of opportunities for reflection and feeling.” In the St. Matthew in particular, he said, Bach deals with the complexity of the narrative by making use of a “colorful orchestra and individual instrumental sonorities to create a very specific affect. This also applies to his use of the various voices”—specifically extremely high soprano for one aria and a sonorous bass for another section. “So the vocal spectrum is as richly used as the instrumental spectrum, which also includes special instruments that are not part of the ordinary orchestra. He introduces the solo viola da gamba; he makes use of a solo lute and recorders,” he added.

The St. John, Wolff noted, was composed on a more modest scale than the St. Matthew in terms of the participating forces. “But at the same time, the text of the St. John Passion is much more dramatic. There is much more tension, there is much more dialogue. There is a very suspenseful trial with multiple dialogue partners that provide a kind of exchange between individual soloists that are part of the musical drama,” he said. “That kind of quick exchange and dramatic procedure is lacking in the St. Matthew Passion, which is a more reflective piece.”