Column Name

Title

Subhead

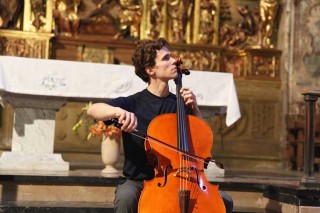

Dane Johansen spent his spring walking Spain's ancient Camino de Santiago pilgrimage route, playing Bach's Cello Suites along the way.

(Photo by Kayla Arend)The Camino de Santiago has been a rite of passage and a spiritual quest for more than 1,000 years. Three hundred years since their creation, Bach’s Cello Suites offer modern listeners a musical journey and an endless source of intrigue and inspiration. The Camino de Santiago and Bach’s Suites are both journeys, timeless in their appeal and relevance and available to all people, regardless of background, age or language. —Dane Johansen (M.M. ’08, Artist Diploma ’10, cello; Pre-College faculty)

Body

While Dane Johansen was at Juilliard studying for his master’s degree, a composer friend regaled him with stories of hiking the Appalachian Trail. Intrigued, Johansen began hatching the idea of walking the Camino de Santiago, the ancient pilgrimage route that winds through northern Spain, and recording Bach’s Six Suites for Solo Cello along the way.

In late May, six years, some 600 miles and endless hours of practicing and performing later, Johansen finished his journey. He had not only played and recorded the suites in 34 churches along the way, he’d also launched a documentary project (tentatively scheduled to come out in January)—and learned an immeasurable amount.

After getting back to New York City, Johansen talked to The Journal about the experience. When he started dreaming about this project, he focused on learning about the suites and “redefining my relationship with them and with Bach in general,” the Alaskan-born cellist said. Afterward, he ended up assembling a film crew of nine who walked the entire pilgrimage with him after he had raised some $30,000 to fund the project.

On average, Johansen carried his cello about 18 miles each day and performed on most days. Early in the trip, he blogged, “Many people have asked me why I am walking with my cello. The simple answer is to share Bach’s music with as many people as possible in some of the world’s most beautiful churches while testing my mind, body, and spirit. The longer answer involves exploring music as a language; one that transcends the expressive limitations of speech and communicates our deepest feelings and emotions.”

The road wasn’t always smooth. Johansen quickly learned that producing a quality recording was hindered by the organic sounds of any live performance—a person coughing in the audience, flies buzzing, papers rustling, and so forth. “There was always something that was beyond my control,” he said, though once he let go, “it was magic.” He started enjoying the experience more, and observed that “as soon as I stopped worrying, my playing got better.” Each venue demanded something different, he added, “but that forced me to play each concert in a different way and develop more flexibility in terms of how I was interpreting the pieces and technically playing them.”

As he made his way to Santiago, Johansen developed a serious following, with each concert turning up a larger audience than the previous one as news of the project made the rounds among pilgrims and locals.

Though the walk ended 40 days after it began, the journey isn’t over yet. While the documentary could be released as early as January, Johansen hasn’t decided whether to use the music he recorded as the backdrop to his film or to release it separately. And that’s partly because his attitude about recording the suites evolved over the course of the journey. Despite having just recorded them, he’s come to feel the music is meant to be performed and is best experienced “as something new and living each time,” he said, much as it was for the people who turned up for his concerts along the way.

For more information, go to walktofisterra.com.