Column Name

Title

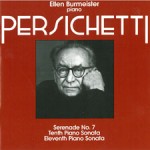

Persichetti: Piano Sonata Nos. 10 and 11; Serenade No. 7. Ellen Burmeister, piano. Starkland R-3016.

Body

A noted professor of composition and theory at Juilliard for some 40 years, Vincent Persichetti (1915-1987) was one of the 20th century’s most influential teachers, counting Einojuhani Rautavaara, Leonardo Balada, Peter Schickele, and Philip Glass among his many students. Here, pianist Ellen Burmeister (professor emerita at the University of Wisconsin, Madison) makes a strong case for three midcareer examples from Persichetti’s distinguished output.

The ruminative 10th Piano Sonata (1955), in four movements without pause, was commissioned by the Juilliard Foundation and premiered by Josef Raieff (piano faculty 1945-2000) as part of the School’s 50th anniversary. (It’s one of several Persichetti works commissioned by the School over the years.) A sequence of descending thirds sets the initial Adagio in motion, its angular edges occasionally interrupted by glints of rhapsodic passagework, leading to a ferocious Presto. In her liner notes, Burmeister writes that she considers the Andante “a love song that is by turns flirtatious, affectionate, pleading, and shy.” But its intimacy is soon upended by the Vivace finale: four minutes of virtuosity and tempestuous octaves. The Serenade No. 7 (1952) that follows is in six brief sections (“Walk,” “Waltz,” “Play,” “Sing,” “Chase,” and “Sleep”) totaling just seven minutes, and although their simplicity might make them attractive to those just beginning their piano studies, their musical charm is equally apparent.

Written a decade after the 10th, the 11th Sonata (1965) is a marked departure; the composer once described it as “gravelly.” Opening with a stentorian Risoluto, the work’s mood is less playful, with sharp contrasts. Brutal chorales introduce dancelike waves of counterpoint; skittering runs may lead to a single note briefly suspended, as if held up for contemplation. Marv Nonn is the engineering wizard here, and if at 47 minutes the program seems a little short, it is only because Persichetti’s music—not to mention Burmeister’s confident playing—whets the appetite for more.

Jeremy Denk Plays Ives. Sonata No. 1, Sonata No. 2, “Concord.” Jeremy Denk, piano. Think Denk Media TDM2567

In addition to playing a mean piano, Jeremy Denk (D.M.A. ’01, piano) is an incisive writer. His notes for this Ives recording include an essay on how the composer quoted Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in the “Concord” Sonata, with illustrations of some of the motifs Ives identified and transformed. A beast that’s almost 100 years old, the “Concord” (1914) seems as fresh as if it were written yesterday, packed as it is with unsettling juxtapositions, harmonic invention, musical quotations, and polyrhythmic madness. Each of its four movements—which pay tribute to the 19th-century Transcendentalist movement in Concord, Mass.—is almost a sonata on its own. One could focus, for example, solely on the unorthodox structure of the sonata’s first movement, “Emerson,” with its massive opening—as Denk writes, “a cadenza of everything”—which Ives then deconstructs over its 15-minute span. Or consider the witty brilliance of the second movement, “Hawthorne,” with its ragtime and marching band references constantly crashing against each other, leaving ghostly trails of hymns in the debris. Then comes “The Alcotts,” a five-minute idyll capturing the quaint beauty of Orchard House in Concord, and the flickering final movement, “Thoreau,” with flutist Tara Helen O’Connor entering just before the end to help conjure the serenity of Walden Pond. At 40 minutes, the sonata makes countless Herculean demands, but Denk’s coolheaded approach makes sense of Ives’s most tangled paragraphs.

The disc opens with the First Sonata (1909), in which three somber (more-or-less) movements alternate with two that are much more disruptive; in the fast portions it’s hard not to imagine the composer chuckling. Denk perfectly judges the composer’s quick sleights of hand, such as the fourth movement’s speedy opening that ushers in a riotous take on the hymn “Bringing in the Sheaves.” The finale incorporates glimpses of two songs used earlier—“Lebanon” and “Where Is My Wandering Boy?”—before ultimately finding, as Denk notes, “the pleasure of nonresolution.”

The ubiquitous-for-a-reason Adam Abeshouse is Denk’s engineer, working confidently in the recital hall at the Purchase (N.Y.) College Performing Arts Center to capture the often overwhelming barrage of detail. And those who can’t get enough of the pianist can sample his thoughts in his entertaining blog, Think Denk (jeremydenk.net/blog).