Title

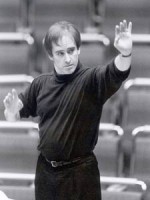

What happens when classical music clashes with its society? This is the question that James Conlon will address this month in the second installation of his two-year residency at Juilliard. Mr. Conlon will collaborate with Ensemble ACJW (comprising artists from The Academy—A Program of Carnegie Hall, The Juilliard School, and the Weill Music Institute); Axiom, Juilliard’s newest new-music ensemble; and members of the Dance and Drama Divisions to present three chamber music concerts that juxtapose music specifically suppressed by the Third Reich—dubbed “degenerate” by the Nazi party—with music that was created out of the party’s reach—music Mr. Conlon calls “generative.”

Body

In recent notes that he wrote about the upcoming concerts, Mr. Conlon elaborated on these terms. “I have co-opted the word generative,” he wrote, “to denote the music that was, in general, composed, performed, and enabled to survive in the relative freedom outside the control of the Nazi suppression. ‘Generative’ because, breathing fresh air, it could celebrate itself and produce artistic offspring. Much of this music was born and/or flourished in Paris. Although almost all these composers felt the effects of the Second World War, they were not dependent on the destroyed German culture milieu for their survival and dissemination.

“Degenerate Music is taken from the term Entartete Musik, which was used by the Third Reich to condemn and ban certain composers in 1938 at an infamous exposition in Düsseldorf. Of course, this is their term, not ours, and the music is anything but degenerate. I use it here simply to refer to those composers whose lives were shortened or creativity disrupted. As a result of the ban, performances and diffusion of their music was limited, their influence was narrowed, and they were rendered barren of progeny, hence ‘non-generative.’”

These concert programs are arranged chronologically, each focusing on five-year segments from the period 1915-30. The composers represented include Varèse, Milhaud, Stravinsky, and Poulenc on the “generative” side and Franz Schreker, Pavel Haas, and Erwin Schulhoff on the “degenerate.” By performing these works side by side, Mr. Conlon says he hopes to demonstrate the great variety of creative activity that was occurring simultaneously across Europe and to restore the context in which these works were created. In a recent telephone interview, he highlighted his goals for this phase of the residency. “I want to show that these works are not out of a mainstream,” he said. “They are not brought in from another planet. They are, in fact, an integral part of what was going on in Europe at the time. The only reason that these works are not known is because they were specifically suppressed.”

“What is interesting about the 'degenerate' composers,” he continued, “is that for the most part, and especially for those who died—and there will be at least two in these concerts who died in concentration camps: [Hans] Krasa and Haas—is that because their music was forbidden … there was no way for it to have any influence on anyone else. The case of Franz Schreker, for instance, is the case of a composer who was extremely successful in his time. He was forcibly removed from his position, the highest academic position in Germany, by the Nazis, and—by most accounts, due to the extraordinary stress through which he was put—had a stroke and died very early.” Mr. Conlon noted that, due to book burnings, shortly after Schreker’s death “his widow could not find a single score in any bookshop.”

“Most of this was simply part of genocide,” he explained. “Degenerate music, in fact, was, simply put, a code word for [music by] Jewish composers. There are exceptions to that. Schreker, for example, was brought up as a Roman Catholic. But they considered him Jewish. That’s the important part.”

In the face of such undeserved and undiscerning persecution, it is no surprise that many composers chose to flee Germany after the rise of the Nazi party. “America benefited twice in the 20th century from catastrophe,” said Conlon. “There was a flood of immigration from 1914-18 and a flood of immigration during the ’30s and ’40s.” Because of this, he said, “our own symphony orchestras had a connection to a very high quality of musical culture. After that generation died out, it was up to us to continue, and what is there today, for better or for worse, is now the legacy of what was left behind.”

Some composers who were forced to come to the United States made illustrious careers here, as Conlon pointed out. For example, Kurt Weill adapted and made an enormous contribution to Broadway. Erich Wolfgang Korngold “created modern film scoring, so his influence is enormous. And, by the way, he learned orchestration and certain compositional techniques from Zemlinsky. So in a certain way, modern film music, through Korngold, is the grandchild of Zemlinsky.”

This phase of Conlon’s residency fully realizes his intention of collaborating with each of the School’s three divisions. Dance and drama students will play an important role in the April 13 performance of Stravinsky’s 1918 Histoire du Soldat—the story of a soldier who strikes an ill-fated bargain with the Devil. However, this is not Mr. Conlon’s first experience with Juilliard actors. “One of the reasons why I chose this work,” he explained, “is because as a student I conducted Histoire in collaboration with two actors from what was the first graduating class of the Juilliard Drama Division, and they were Kevin Kline and David Ogden Stiers.”

Mr. Conlon’s primary goal, it seems, is generating as much exposure as possible for this repertoire. The task is not easy, and he expects no instant results. “People come in with a lot of preconceptions,” he said. “Everything from ‘This can’t be very good because I’ve never heard it’ to ‘Well, this is all about concentration camps’ to ‘It’s all the same.’ I want people to, in fact, experience what the thing is, not what they imagined it to be.”

Indeed, he remains philosophical about the endeavor and his role within it. “This is not a project for me now; it’s a life’s work, because I will not live to see the end of it. My hope is that, very gradually, this music will be reintegrated into the tradition of classical music from which it was born and to which it belongs. It is not something that can be accomplished on the short term. It is not tokenism, tipping one’s hat to certain composers or compositions; it’s not about making an event. It’s about a slow process of putting this music back into the public, so that audiences hear it, musicians play it, and eventually that future generations will take its existence as a given and play it in the context of everything else they play.”

Given the fate of the composers represented here, it might be tempting to engage in flights of conjecture. What if the Nazi party had not come to power? What if these artists had not been the target of a ruthless cultural purge? Conlon responds: “What-ifs are, of course, a favorite game—but this is not about what would have happened; it is about what exists. This music exists. It must be played, in my view. That, to me, is more important.”