Title

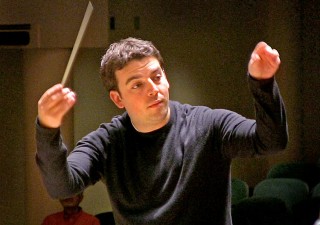

Pre-College alum James Gaffigan returns to conduct the Juilliard Orchestra on April 20.

(Photo by Peter Weinberger)This spring sees the return of James Gaffigan as guest conductor of the Juilliard Orchestra for a program of Mahler and Bartok. The New York native and Pre-College alum, who at 34 is just leaving the wunderkind phase of his career, is in his second full season as chief conductor of the Lucerne Symphony Orchestra and principal guest conductor of the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra. His appearance at Juilliard, on April 20, comes close on the heels of a complete Beethoven symphony cycle with the Qatar Philharmonic and precedes his May 17 debut with the BBC Symphony.

Body

One of the busiest and most feted conductors of his generation, Gaffigan rose to prominence quite young. A bassoonist in Pre-College, Gaffigan did his undergraduate work at the New England Conservatory and, upon receiving his master’s degree from Rice’s Shepherd School of Music, he began a three-year tenure as assistant guest conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra, working under Franz Welser-Möst. This post was followed immediately by a similar engagement at the San Francisco Symphony, where he worked with Michael Tilson Thomas. Gaffigan’s international career was secured when, at the age of 25, he took first prize at the Sir Georg Solti International Conductors’ Competition.

Known for his vast repertoire and seemingly boundless energy, Gaffigan will doubtless bring vigor and insight to his performances of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony and Bartok’s Second Violin Concerto at Juilliard. In a recent conversation with The Journal, his ebullience certainly shone through. “The combined colors and contrasts of the Bartok and Mahler will make for a really great program, so I’m really excited,” he said. “I think it’s a perfect way of showcasing the orchestra.” He also relished the thought of the ample rehearsal time afforded by conservatory orchestras, saying, “You really have the opportunity to work in great detail on works like Mahler Four. If I were doing it in Detroit or Cleveland, we’d have to put it together within two days, but at Juilliard we have the opportunity to work in much greater detail. When you learn pieces like that, you really do remember them for life.”

Mahler’s Fourth Symphony had its premiere under the baton of the composer in 1901. With a duration of about one hour and lacking trombones and tuba, it is one of Mahler’s more modest creations. The four-movement work culminates in a strophic setting for soprano soloist of “Das Himmlische Leben” (“The Heavenly Life”), one of the poems from the popular collection of German folk poetry Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Magic Horn). Mahler originally intended to use the song setting, composed almost a decade earlier as a stand-alone work, in his Third Symphony, which is peppered with motives from the song, but later decided to make it the culmination of a new symphony, which became his fourth.

To Gaffigan, the Fourth is one of Mahler’s most accessible works. “Everyone can relate to this music—this young child commenting on the paradise of heaven,” he said. “It’s a beautiful statement. I think the success of Gustav Mahler has to do with human beings relating to one another. I mean, if anyone is writing a personal piece of music, it’s Mahler. There’s no hiding, it’s just him.”

Mahler’s prowess as a conductor (he was musical director of the Vienna State Opera from 1897 to 1907) is also an important consideration to Gaffigan. “It’s exciting to know that this guy was constantly revising based on his rehearsal process,” he said. “The fact that he was able to do his own rehearsing and could hear what worked and what didn’t work is something many other composers didn’t have. And I think he was really honest with himself. He’s so meticulous with his markings, because he knew there are so many different possibilities. I find it a big plus that he was a conductor.”

In his Second Violin Concerto, Bartok unleashes the full force of his lyrical and dramatic gifts. From its ravishing opening theme to its breathless finale, this proves to be one of his most important and compelling works. Completed in 1938, when Bartok was at the height of his creative powers, the concerto fuses many compositional philosophies and techniques, incorporating 12-tone melodies, rigorous sets of variations, and references to nationalistic folk music.

Gaffigan said he is pleased to be bringing this program to his hometown, and that his wife, writer Lee Taylor Gaffigan, and toddler daughter Sofia can join him for the trip, though in general he feels he has found a good balance between his professional and personal lives. “When I’m home with my orchestra in Lucerne, I get a lot of work done and have a lot of family time,” he said. “The rest of the time, we have a two-and-a-half- or three-week rule that I can’t be apart from them. We might even make it a two-week rule because now at [Sofia’s] age, so many things are happening.”

Of the Juilliard trip, Gaffigan said, “I have amazing memories of being in Pre-College there. It opened my world. Spending all day Saturday for a 16- or 17-year-old with all those musicians who are like you, really was just heaven. Even though the building has changed, it still gives me butterflies to walk in there!”