Column Name

Title

The ever increasing speed of change in the world of classical music in New York causes me to contemplate the challenges faced by young singers of today just out of college or conservatory, as opposed to what my generation dealt with 40 or 50 years ago. Though today’s music scene is vastly different from that of my youth, the hurdles, in a sense, remain the same: artists must hone their craft to the highest level of which they are capable, while finding their way ahead within the parameters of the local musical life of their own era.

Body

In talking with a few contemporary colleagues, I came up with some varied recollections of the New York music scene from the late-’50s on into the ’60s and ’70s and beyond.

Radio was once an all-powerful medium for the propagation of careers in classical music. Robert Sherman’s program on WQXR, The Listening Room, aired live every weekday and featured established performers as well as emerging young artists, many of them vocalists, who spoke at length and then sang or played—something unimaginable in today’s media. In those halcyon days the daily doings of New York’s classical music life were considered newsworthy! George Jellinek’s The Vocal Scene was another program celebrating song, and major networks such as NBC and CBS devoted a good deal of radio and television time to classical song and opera—The Voice of Firestone, The Bell Telephone Hour,and the NBC-TV Opera, to name a few. Even that most popular of earlier television programs, The Ed Sullivan Show, presented the likes of a young Itzhak Perlman or Maria Callas and Franco Corelli in the course of a season.

The plethora of concert reviewers that existed in earlier times made it possible for a young performer’s career to get kick-started with a single concert appearance that could generate myriad reviews. A prime example is aforementioned faculty member Robert Sherman’s famous mother, pianist Nadia Reisenberg, whose career went into high gear after she received 35 rave reviews for her debut in the 1920s. The number of newspapers and reviewers has been gradually on the wane ever since. Still, up until at least the ’80s, there were multiple music critics covering the concert scene. Names like Virgil Thomson of The New York Herald Tribune, Harold Schonberg of The New York Times, and Harriet Johnson of the New York Post were only a small part of an extraordinary roll call of the ongoing vitality and variety of New York musical opinion. Today, a singer or instrumentalist can spend a small fortune on a debut and be lucky if onereview (good or bad) comes out of it. Sadly, many of today’s concerts thereby come and go in a blaze of anonymity.

It was an era when managers groomed young singers for a real and meaningful place in the singing establishment. My own manager, the venerable Thea Dispeker, held monthly auditions for young singers; she listened to everyone who wanted to be heard and then signed up those she liked best. She offered good career advice to everyone who auditioned, even recommending unsigned applicants to other managements—a kind of polite humanity that is found less often in the profession today.

Every age has its compensations, and just as one service once available in an earlier epoch is taken away, another one emerges as the gift of modernity. A case can certainly be made for the numerous opportunities available currently on the Internet, and especially on YouTube. Today’s creative young performers can now get their wares before an audience, with or without the help of the traditional media.

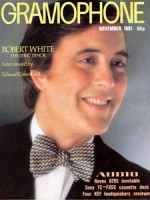

The recording industry, first on 78s, then LPs and finally CDs, has gone through various phases of being downsized and now seems all but extinct. How different it was even in 1976. I sent out a tape then of one of my vocal recitals to all the major labels and within the space of a month I was signed to a solo recording contract with RCA Red Seal records. This was a huge step forward in my career. It hardly happens that way anymore!

Singers in the late 1950s and ’60s were seldom out of work, perhaps because there was so much less specialization in those days. In the course of a single season one could take part in professional performances ranging from 12th-century liturgical dramas, to Handel operas, to the latest mid-20th-century works of Xenaxis, Hindemith, and Stravinsky. Audiences for lieder were swelled by highly educated German-speaking exiles.

Columbia Management’s “Community Concerts” provided numerous vocal recital bookings across the country. They didn’t pay particularly high fees, but a singer could go on an extended tour and come home with a guaranteed nest egg. A young singer could also derive a decent income from the many “professional” choral groups that flourished in New York for concert performances of operas and oratorios. Just before graduating from Hunter College in 1959 (I received my master’s in voice from Juilliard nine years later), I performed my first professional classical gig—two operas and a song concert at the 92nd Street Y. Purcell’s Fairie Queen and Monteverdi’s Orfeo, plus an evening of 20th-century vocal chamber music with two wonderful sopranos, Judith Raskin and Bethany Beardsley, and tenor Charles Bressler, provided me with a glorious introduction to the joys of singing for a classical public.

Singers not only earned a reasonable living in New York then, but exquisitely low rents made it possible for beginners—rich or poor—to actually dwell in Manhattan. My first apartment was on 10th Avenue at 57th Street (the heart of the concert world) ... five rooms in a walk-up, for $80 a month! Voice lessons with Sergius Kagen, and subsequently Beverley Johnson, were about $30 to $40 an hour. An artist could survive and even flourish in conditions such as these.

On the very day I write this article the most influential New York classical music radio station of the past 73 years—WQXR—is changing channels and severing its ties with The New York Times. WQXR closes shop on 96.3 FM and will take up residence on NPR through its local WNYC station at 105.9 FM. Within a few short hours, classical radio, as we grew up knowing it in New York, might well be forever changed.

How musical life has evolved in our city over the last four decades! Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose—the more things change, the more they stay the same ... meaning, of course, that every young performer of any age is ultimately responsible for dealing with his or her career with a well-informed sense of their own Zeitgeist and talent. Each of us in any age is the architect of our lives and careers. It’s not all to be left up to chance, change, or wishful thinking.

(With special thanks for their reminiscences to Robert Sherman, Thomas Z. Shepard, Russell Oberlin, Christa Damestoy, and Graham Johnson.)