Title

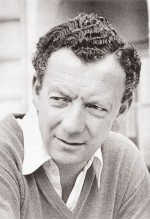

On November 17, 1936, five days shy of his 23rd birthday, the English composer Benjamin Britten (1913-76) was apparently at loose ends. He wrote in his diary, “we’ve got to start work on the Capitol Film stuff tomorrow, which means that it is all up for the other stuff … for a bit.” The young composer had recently started making inroads in the world of writing for film and radio, which provided welcome income, but sometimes at the expense of his other compositional work. Britten, who often wrote diary entries in the present tense, went on: “However in desparation [sic] I write a duet (Auden’s words) in the morning & early afternoon—very light & Victorian in mood.”

Body

The duet (and words) that Britten was referring to was a setting of the poet W.H. Auden’s Underneath the Abject Willow.

Underneath the abject willow,

Lover, sulk no more:

Act from thought should quickly follow.

What is thinking for?

And it’s true, the song does have a light quality. Britten’s setting of its first stanza is so light and airy in fact—frilly, nonchalant piano figures and sing-song, folk-inflected vocal lines—that it seems almost as if the composer was willfully disregarding Auden’s message. In fact, Britten had yet to acknowledge, let alone grapple with, his homosexuality, and had never attempted a fully mature, romantic relationship. His unblemished existence stood in stark contrast to Auden’s relatively libertine ways. Indeed, Britten frequently found himself in intense, though completely chaste, relationships with younger boys, no doubt substituting juvenile companionship for deeper intimacy. According to Britten biographer Paul Kildea, Auden thought these “friendships with schoolboys were evidence of Britten fumbling round the edges.” Auden dedicated Underneath the Abject Willow to Britten (who, despite being only six years Auden’s junior, regarded the poet as a mentor and father figure) to cajole and encourage the composer toward a more authentic life. At this point in his development, Britten was, according to scholar Humphrey Carpenter, an “individual restraining himself from full emotional commitment.”

Emotional commitment is unlikely to be in short supply when a crop of promising young singers from the Ellen and James S. Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts takes the stage at Alice Tully Hall with Brian Zeger (M.M. ’81, piano) the institute’s artistic director, in an all-Britten song program on December 3. This will be the third installment of Songfest, an annual survey of a single composer’s vocal work.

“Britten’s songs are central repertoire for recitalists in their perfect marriage of superb texts with highly idiomatic music,” Zeger told The Journal. “His writing for the voice is always expressive, always attuned to the colors and strengths of specific voice types.” In addition to Britten’s extraordinary duet setting of the Old Testament story of Abraham and Isaac (hearing his evocation of the voice of God is worth the price of admission alone) and the intensely dark 1965 song-cycle Songs and Proverbs of William Blake, Songfest also features a selection of Britten’s folk song settings accompanied by piano and guitar. These are divided into two categories, “Rejoicing” and “Sorrowing.” Many deal with subjects to which Britten, whose birth centennial is being celebrated this year, was always drawn: the maritime traditions of coastal England in “Sailor-Boy” (I would not be a blacksmith / That smuts his nose and chin, / I’d rather be a sailor-boy / That sails thro’ the wind); or the loss of innocence in “O Waly, Waly” (I leaned my back up against some oak; / Thinking that he was a trusty tree / But first he bended, and then he broke; / And so did my false love to me); or the ambiguities of the heart in “Mother Comfort” (My longing, like my heart, beats to and fro / Oh that a single life could be both Yes and No.)

In other words, Britten got to the heart of the matter in song, an art form that he returned to throughout his professional life, as both composer and pianist. “One of the subtlest and most refined pianists of his era, Britten could shape the piano writing to illuminate text and voice,” Zeger said. Britten plumbed the depths of poetic meaning so that even a simple seeming folk song text is imbued with layers of meaning, its theme amplified by musical turns of phrase that often display a simple sophistication. He conjured up worlds in his songs, amusing and unsettling in turn, by letting things be said, and even more potently, unsaid.

Case in point: that November 1936 diary entry ends with a cryptic, if tantalizing, sentence: “Auden and I meet for tea at the M.M. & discuss odd things.” It’s impossible to know, of course, what those odd things were, but it seems safe to assume they weren’t totally benign, at least if the second verse of Auden’s Underneath the Abject Willow, a call-to-arms to a young man still figuring out his place in the world, is any indication:

All that lives may love;

why longer

Bow to loss

With arms across?

Strike and you shall conquer.