Column Name

Title

Subhead

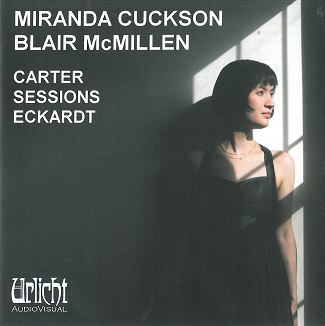

Music of Elliott Carter, Roger Sessions, and Jason Eckardt. Miranda Cuckson, violin; Blair McMillen, piano. (Urlicht Audiovisual UAV 5989)

Body

Roger Sessions, who taught at Juilliard from 1965 to 1983, wrote his knotty Sonata for Solo Violin—his first exploration of dodecaphonic writing—in 1953. On this impressive recording, Miranda Cuckson, who attended Juilliard Pre-College and went on to earn bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees at the school, has tackled this virtuosic half hour of complexity. Cuckson shows masterful control over the peripatetic line—now leaping into the instrument’s upper reaches, now almost motionless in a mass of double stops. A capricious second movement marked “Molto vivo” displays Cuckson’s agility, and the third movement, marked “Adagio e dolcemente,” is filled with intimacy. The finale is a virtuosic march, with nods to motifs in the three previous sections.

Roger Sessions, who taught at Juilliard from 1965 to 1983, wrote his knotty Sonata for Solo Violin—his first exploration of dodecaphonic writing—in 1953. On this impressive recording, Miranda Cuckson, who attended Juilliard Pre-College and went on to earn bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees at the school, has tackled this virtuosic half hour of complexity. Cuckson shows masterful control over the peripatetic line—now leaping into the instrument’s upper reaches, now almost motionless in a mass of double stops. A capricious second movement marked “Molto vivo” displays Cuckson’s agility, and the third movement, marked “Adagio e dolcemente,” is filled with intimacy. The finale is a virtuosic march, with nods to motifs in the three previous sections.

The clash between individuals is often paramount in the music of Elliott Carter (faculty 1966-84), and in his Duo (1973), the musicians often travel along separate paths. In the opening pages, pianist Blair McMillen (M.M. ’95) plays solemn chords spaced with rests while Cuckson begins with legato lines that evolve into athletic vaults from the G string to the violin’s highest register. Later, the piano line becomes violent and more agitated as the violin passages become calmer and more transparent. Cuckson shows formidable technique, navigating Carter’s wide-ranging melodic lines, and McMillen is equally meticulous in the austere piano role.

Jason Eckardt’s Stromkarl (which Cuckson commissioned) began with a kernel of 17 measures he wrote in 2007 as a wedding gift for friends. He expanded the violin part with Carter’s textural approach in mind, and added piano to match what Eckardt describes as Sessions’s “muscularity and melodic inventiveness.” In the first half, Cuckson unleashes solo scrapes, glissandos, and tremolos before the piano enters in appealing contrapuntalism. The dialog continues almost without pause, as Cuckson ascends ever-higher and McMillen dives in the opposite direction, to the piano’s rumbling lower notes. It’s a dazzling display. Ryan Streber (Pre-College ’97; B.M. ’01, M.M. ’03, composition) engineered the recording at Oktaven Studio in Yonkers, N.Y., and captured the duo’s sizzle and sparks with admirable fidelity.

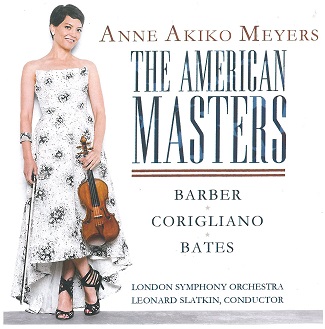

The American Masters: Music of Barber, Corigliano, and Bates. Anne Akiko Meyers, violin; Leonard Slatkin, conductor; London Symphony Orchestra (EOne EOM-CD-7791)

In his program notes for this release, Juilliard composition professor John Corigliano observes that Samuel Barber “never liked his Violin Concerto”; specifically, he felt the energetic finale didn’t quite fit with the initial two movements. But if Barber had heard this version by Anne Akiko Meyers (Pre-College ’87; Certificate ’90), Leonard Slatkin (B.M. ’67, orchestral conducting), and the London Symphony Orchestra, he might have had a change of heart. Slatkin also recorded the concerto in the 1980s with Elmar Oliveira and the Saint Louis Symphony, and he has a real affinity for Barber’s masterful phrasing. The L.S.O. shows marvelous versatility, whether pulling back slightly to let Meyers shine, or surging forward in Barber’s voluptuous climaxes. When the frenetic third movement arrives (presto in moto perpetuo), Meyers uses light bow strokes for the perfect spicy tonic to the lush melodies of the earlier movements.

In his program notes for this release, Juilliard composition professor John Corigliano observes that Samuel Barber “never liked his Violin Concerto”; specifically, he felt the energetic finale didn’t quite fit with the initial two movements. But if Barber had heard this version by Anne Akiko Meyers (Pre-College ’87; Certificate ’90), Leonard Slatkin (B.M. ’67, orchestral conducting), and the London Symphony Orchestra, he might have had a change of heart. Slatkin also recorded the concerto in the 1980s with Elmar Oliveira and the Saint Louis Symphony, and he has a real affinity for Barber’s masterful phrasing. The L.S.O. shows marvelous versatility, whether pulling back slightly to let Meyers shine, or surging forward in Barber’s voluptuous climaxes. When the frenetic third movement arrives (presto in moto perpetuo), Meyers uses light bow strokes for the perfect spicy tonic to the lush melodies of the earlier movements.

Corigliano wrote Lullaby for Natalie (2010) for violin and piano to honor Meyers’s not-yet-born oldest child, and in this subsequent orchestration, nestled in a tender melody, fragments of the Barber seem to appear. (In the notes, Corigliano recalls Barber as his mentor.) In Meyers’s hands, the piece becomes a sweet interlude between the two concertos.

Inspired by the dual nature of the Archeopteryx—a bird/dinosaur hybrid from 150 million years ago—Mason Bates (Barnard-Columbia-Juilliard Exchange ’99; M.M. ’01, composition) created his Violin Concerto (2012) for Meyers. As he writes, the violin part “inhabits two identities: one primal and rhythmic, the other elegant and lyrical.” But this idea didn’t come easily; Bates confesses on his website, “I’ve always looked fearfully at the strings, the most-heard (and most populated) section of an orchestra.” Abandoning his often-used electronics, he conquered that anxiety and wrote this entertaining blend of soaring strings, jazz, and colorful percussion (including horse hooves) to frame the soloist. In the finale, “The rise of the birds,” Bates echoes the brilliance of Barber’s finale, as Meyers takes flight above the orchestra.

Silas Brown recorded the program at L.S.O. St. Lukes in London, a former church that is now the orchestra’s education center as well as a site for recordings and concerts. He captures the sunny glow of the Barber and Corigliano as well as every spunky, percussion-laced detail of the Bates.