Title

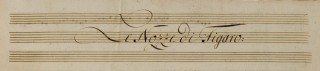

Detail of title page of a copyist manuscript of Le nozze di Figaro, from the Juilliard Manuscript Collection.

What a character Emanuele Conegliano was! Born to Jewish parents in Ceneda within the Republic of Venice in 1749, he was converted to Catholicism in 1763 (on his widowed father’s remarriage to a Catholic woman) and renamed Lorenzo Da Ponte after the bishop who baptized him. Ordained as a priest in 1773, Da Ponte became well known as a chaser of married women (shades of Don Giovanni), which eventually led to his expulsion from his homeland. In 1780 he landed in Vienna, where he became Emperor Joseph II’s official court poet. In the course of a decade, he created opera librettos for composers including Antonio Salieri, Martín y Soler, and, of course, the inimitable Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Body

What fun—what utter delight—these two capricious artists, Mozart and Da Ponte, must have had concocting their erotic, seductive, amazing comedies, starting with Le nozze di Figaro (1786) and then moving on to Don Giovanni (1787) and Così fan tutte (1790). (By the way, Da Ponte wound up in New York City, of all places, teaching Italian language and literature at Columbia College; he died in New York in 1838.)

As to the origin of the names of the characters in the three operas, Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (1732–99) provided Mozart and Da Ponte with the colorful bunch we know and love from Le nozze di Figaro. Of the 10 major players in the opera, only Barbarina was a 1786 invention; she was called Fanchette in the French play (the French -ette and the Italian -ina each indicating her youth).

Intriguingly, Beaumarchais, the playwright who created La Folle Journée, ou Le Mariage de Figaro (The Mad Day, or The Marriage of Figaro) in 1778, was born Pierre-Augustin Caron. When he married in 1756, he took his new name from a piece of land his wife owned, “le Bois Marchais,” and his biography reads much like Da Ponte’s in that he was, among other things, a diplomat, musician, publisher, spy, fugitive, and revolutionary.

A number of the main characters’ names in Le nozze have explicit and implicit connotations that surely led Da Ponte and Mozart to make many of their ingenious compositional choices. First of all, the Latin root of the name Figaro is fig-, and the verb figuro, figere means to shape, form, establish, mold. Indeed, the title character is a barber and valet, one who dresses, bathes, and grooms his master, giving Count Almaviva a “proper” form and limiting his “freedoms” just as he controls his appearance. The Italian words for soul (“alma”) and life (“viva”) suggest that the Count represents the libido, the life force, the male seeking and willing self-fulfillment—a lothario whom Figaro needs to control. The younger version of Almaviva, Cherubino (Chérubin in the French), is the Cupid of the play, a cherub of desire, erotic love, and affection, a “little angel” who can destroy as well as create, wound as well as entice.

Along with this single -ino, the opera has three –inas Rosina, Marcellina, and the already-mentioned Barbarina. Countess Rosina (Rosine) is the little rose, a symbol of purity, beauty, and spiritual love. Having married into the aristocracy, she is the young and loyal wife of Almaviva. Marcellina (Marceline) is neither young nor sweet, and her name may be derived from that of the Roman military warrior Marcus Claudius Marcellus (c. 268–208 B.C.E.), for Figaro’s mama is, until Act III at least, one tough gal. Yet her diminutive name may be hinting that she will be revealed as the loving and protective mother of Figaro before the opera ends, and we may even come to like her.

Basilio’s (Bazile’s) name is derived from a legendary reptile, the Basilisk, that venomous king of serpents with the deadly glance from his malignant eye. The Basilisk, like his operatic counterpart, is a deceitful spirit and appears in literature by such authors as John Gay in The Beggar’s Opera, Percy Bysshe Shelley in the Ode to Naples, and J. K. Rowling in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

The Hebrew name Shoshannah, which leads to Susanna (Suzanne), is derived from the word for lily. Thus, Le nozze presents us with a rose and a lily, the lily serving as another symbol of beauty, purity, and innocence. This may very well be one of the ways in which Beaumarchais implies the equal footing of the servant and her mistress. The symbolic essence and rivalry of the lily and the rose in mythology, religion, and literature could not have escaped the attention of Beaumarchais or Da Ponte. The Bible’s Song of Solomon opens its second chapter with the verse, “I am the rose of Sharon, the lily of the valleys.” And as an example of floral rivalry, in 1782 (midway between the framing of the texts of Beaumarchais and Da Ponte), William Cowper’s lyric poem The Lily and the Rose was published in London, and it told of these flowers competing for the title of Queen of the Garden, an honor that they wound up sharing. Whether or not Beaumarchais or Da Ponte knew of this particular poem or its poet, they must have understood the symbolism of the flowers. This said, could it be just a coincidence that the opera’s human rose and lily, donning each other’s clothing, undo their male partners in an atmospheric garden at the denouement of Le nozze?

Along with such later operas as Maria Stuarda, La traviata, Otello, Pelléas et Mélisande, and Salome, Mozart and Da Ponte’s Le nozze di Figaro lived as a play before becoming an opera. It springs to life to a great extent because of its unforgettable characters; and with rascals such as Beaumarchais, Da Ponte, and Mozart breathing theatrical and operatic life into them, The Marriage of Figaro was bound to please its audiences.

Get a behind-the-scenes look at the Juilliard Opera production of Le nozze di Figaro in this video.