Column Name

Title

If you have never visited the International Center for Photography, this is an excellent time to do so: The four exhibitions now on view are about as diverse as you can get. “The Mexican Suitcase”—an expansive collection of Spanish Civil War photos by Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and Chim (David Seymour) that takes up the entire first floor—opened in September, and it has been so successful that it has been extended. The three other not-to-be-missed exhibits share space on the lower level. Two deal with vernacular and small-town America: “Take Me to the Water” features photographs of river baptisms taken between 1880 and 1930; the other, “Jasper, Texas,” focuses on pictures of mid-20th-century life by photographer Alonzo Jordan.

In his 2004 photograph Competition, Wang Qingsong filled an empty soundstage with propaganda and advertising posters and climbed a ladder to “address” the audience—but no one is listening to him.

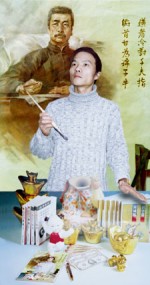

(Photo by Photo by Wang Qingsong)Wang Qingsong’s Pick Up the Pen, Fight to the End, is a play on a well-known Cultural Revolution propaganda poster.

(Photo by Photo by Wang Qingsong)Body

The fourth I.C.P. exhibit, “When Worlds Collide,” the photographs of Wang Qingsong, takes on the mammoth subject of contemporary China in an up-to-the-moment, dazzling, and explosive way. While all four of these exhibits are well worth seeing, because of my personal experience, I’d like to concentrate most of my column on Wang’s work.

I first traveled to China in 1986, and at the time, I never could have imagined an exhibition like this one. I went to Beijing at the invitation of several professors at the Central Academy of Art who had asked me to present the entire history of Western art in two hourlong sessions. At my first lecture, I sensed that the students were bored, and maybe even annoyed. Fortunately, a young art-history student who translated my talk told me the truth: “They already know that,” he said; “they want to know what’s happening now!” So for my second lecture I tore up my prepared notes and instead drew maps of uptown and downtown art scenes in New York. Now the students evinced excitement and enthusiasm, many of them inviting me to see their own work. Proud that they had rebelled against old rules, they were making oil paintings of nudes, reminiscent of what American artists had produced in the early part of the 20th century. At the time it didn’t seem modern to me, but now I realize that in their world, nudity in art was as groundbreaking as it had been 100 years ago in the U.S.

Ironically, Wang, who was 22 at the time, could easily have been one of those students in my lectures. He wasn’t; he arrived in Beijing from northeastern China, where he had been supporting his family by working in an oilfield while applying to art schools, only in 1993.

Once he had reached the capital, the poor and relatively unknown Wang soon became involved with Gaudy Art, the first development in Chinese art to reflect the consumerism and get-rich-quick schemes of the changing social situation. It was this short-lived but influential movement and others like it that helped attract the attention of the rest of the world to contemporary Chinese art. (Interestingly, until about 1990, Sotheby’s did not even hold auctions of Chinese contemporary art. But then, within a few years, it sold nearly $200 million worth of Asian contemporary art, most of it by Chinese artists. By 2000, individual contemporary Chinese paintings sold in New York City brought more than $6 million.)

According to curator Christopher Phillips, the title of the I.C.P. exhibit, “When Worlds Collide,” refers to three kinds of collisions: political and cultural conflicts between traditional and contemporary China, commercial tensions between China and the West, and the aspirations and realities of migrant workers moving to urban China.

The first set of photos juxtaposes a well-known poster from the time of the Cultural Revolution, with one of Wang’s staged photos. In the original, a young girl wearing the red scarf of the Young Pioneers, the Communist youth group, stands with brush poised to celebrate the spirit of Mao Zedong, whose Little Red Book (published in 1964, the year of Wang’s birth) is on the table before her. In Pick up the Pen, Fight to the End, Wang replaces the girl with himself. But instead of revolution, capitalism lies before him, in the form of dollar bills and kitsch. Humorously, he includes a tiny reproduction of this very photo on the table. In another photo, he depicts himself as a many-handed modern incarnation of Buddha seated upon a Coca-Cola lotus, and grasping money, beer, cigarettes, and a red flag. Some huge photographs highlight nudes, graffiti, and other subjects that were taboo in China until recently. Wang also often parodies Chinese scrolls or western iconic paintings in his photos.

The artist, like a theater director, stages all his photographs, assembling actors and objects into empty film studios, warehouses, and the like. One of his strongest—and most horrifying—images in the show is Archaeologist (2004). In it, Wang assembled 30 nude models in a 9-by-24-foot pit and covered them with mud to simulate bodies long dead. In a metaphorical meditation, an “archaeologist” (a self-portrait) sits in the middle examining the evidence for what the artist has said are his fears that contemporary Chinese are “dead in mind and spirit.” The 55.12-by-33.46-inch chromogenic print summarizes some of these feelings.

Wang captures China’s lightning-paced, laserlike progress in his dynamic photographs and videos (there are three of the latter in the I.C.P. show). Perhaps no photograph in the show demonstrates this better than the dizzyingCompetition of 2004. For it he rented an empty Beijing movie soundstage, and filled it with hundreds of hand-drawn fake advertisements for Citibank, McDonalds, Toyota, and Chinese brands. In the photo he stands on a ladder, megaphone in hand, as if addressing a rally. But no one listens. Ladders and scaffolding veer off in crazy directions, garbage is scattered on the floor, and the viewer’s eye goes mad trying to focus on anything.

The question of who is paying attention—to art or anything else—is a particularly fraught one in China. Wang’s work is controversial in China, though not nearly as much as that of his friend Ai Weiwei, whose Shanghai studio was recently destroyed by government censors. At a press preview for the show, Wang was asked what he thought of what had happened to his friend. He replied that he thought Ai was happy about it—the attack on him and his art had brought him attention in a way that acclamation never could. With this exhibit, Wang certainly captures the attention of viewers with his mordant commentary on contemporary China.

“When Worlds Collide” and the other exhibitions mentioned in this article run through May 8 at the International Center for Photography, 1133 Avenue of the Americas at 43rd Street. For museum hours and more information, visit icp.org or call (212) 857-0000.