Title

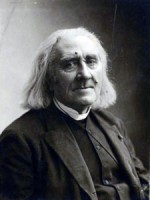

Le concert, c’est moi! With these words, Franz Liszt transformed the very notion of the recital. In fact, he even coined the term recital. Liszt was the greatest piano virtuoso of the 19th century, and perhaps of all time, and his marathon concert tours of 1838 to 1847 grabbed hold of his audiences like a drug. A quick glance at the list of works programmed during his virtuoso years is awe-inducing for any modern-day pianist.

Body

However, the brilliance of Liszt lies not only in his dynamic pianism, but also in his career as a conductor, his legacy as a great pedagogue, and most importantly, his immense oeuvre of compositions. As piano faculty member Jerome Lowenthal told The Journal, “Liszt in his early years more or less invented the recital and in his later years more or less invented musical modernism. A superstar performer who gave up performing at 35 in order to compose and to foster the music of his contemporaries, a passionate reader and connoisseur of literature, an inspired and inspiring teacher, he was music’s indispensable man and the ideal model for a Juilliard student.”

To honor Liszt’s 200th birthday (October 22, 2011) and celebrate the ingenuity and diversity of his works, the Literature and Materials Department’s Liszt Festival at Juilliard will take place from January 18 to 22. It will feature five lecture-recitals that I will co-host with other members of the faculty. Each will focus on a different aspect of Liszt’s compositional output, including “The Sacred and the Diabolical” (co-hosted by Lowenthal; January 18), “The Refinement of an Art: Transcription” (Veda Kaplinsky; January 19), “Diversity in the Songs” (Margo Garrett; January 20), “Forging New Paths to the Future” (David Dubal; January 21), and Innovation and the Sonata (Kendall Briggs; January 22).

When asked why it is important for Juilliard to have such a festival, Provost and Dean Ara Guzelimian said, “Liszt is one of the most endlessly intriguing musicians of the 19th century. Even when we think that we know him and his music, there is so much left to surprise us at every turn. He was everything—virtuoso, composer, impresario, activist, flamboyant public and private figure, even a spiritual figure.” Given that Juilliard encourages its students to approach their art from an informed perspective, Guzelimian described the festival as “another ideal intersection between performance and scholarship.” (And besides, Liszt’s godson, Frank Damrosch, founded Juilliard.)

This intersection will be put on display throughout the festival, but especially on Saturday, January 22, when Juilliard D.M.A. candidate Alex McDonald takes the stage with Briggs to discuss, and then perform, the monumental Sonata in B Minor. McDonald said of Liszt, “His greatest masterpiece would arguably be his Sonata in B Minor, which may be the most significant contribution of the 19th century to not only sonata form but also to the sonata repertory. The work’s narrative qualities have evoked at least half a dozen programmatic interpretations ranging from the damnation of Faust to the salvation of humanity.” The discussion will illuminate the fascinating innovations in the sonata, including Liszt’s use of thematic transformation and his revolutionary manipulation of the sonata archetype.

Less widely known among Liszt’s compositions are the six dozen songs he wrote over the course of his career. Linguistically and stylistically diverse, Liszt’s vocal genres include the German Lied; French mélodie; and Italian, English, and Russian song. He was a master of idiosyncratic piano writing, and his understanding of instrumental technique found its way into his vocal writing as well. Garrett noted, “Liszt songs always seem to bring out the best vocalism in singers. The singers often sound better in his songs than in those of other great composers.”

The festival will feature several works from his later period, such as La Lugubre Gondola and Nuages Gris, along with a look at the famed innovations Liszt offered to piano technique. From 1877 on, Liszt battled with depression as his health began to deteriorate. Alan Walker, the great biographer of Liszt, wrote, “This late music is replete with funeral marches, elegies, and memorial music of all kinds.” The compositions from this period are emotionally profound, but more importantly are some of the most harmonically adventurous and texturally innovative works of his day. As Briggs observed, “Before Debussy found his voice, Liszt had created the concept of impressionism. He is, without question, the prophet of the 19th century.”