Title

The Juilliard Piano Department launched its new Piano Scope program with an exciting evening devoted to the works of Debussy. The first event in what will hopefully become a lively tradition—Claude Debussy: 24 Preludes, 24 Pianists—was hosted by guest pianist Richard Goode and curated by Juilliard faculty member Aaron Wunsch. The concert, on October 24, was the culmination of a series of master classes that brought together two dozen students from across divisions of studio and degree programs to delve into Debussy’s 24 Preludes, his beloved and seminal contribution to the piano repertoire, and to explore the composer’s extensive and fruitful relationship with the visual arts.

Body

The Preludes, divided into two books of 12 and composed between 1909 and 1913, have been favorites of pianists and audiences since their premieres. These short solo works, with their mysterious and alluring postscript “titles,” combine great expression and imagination with extreme economy. One is instantly drawn in but, like a fleeting reverie, each ends before interest wanes. In short, they are perfect miniatures.

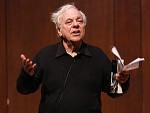

“If I had to sum up the music of Debussy in one word, it would be ‘enchantment.’ Everything combines to create a great imaginary world,” Goode told the audience. To help the 24 performers enter this imaginary world, Goode had coached each of them in a trio of master classes prior to the concert.

To assist the audience in entering this world, Wunsch began the evening with an imaginative presentation that illuminated Debussy’s philosophical goals by discussing the visual artworks that had inspired him.

Debussy, born 150 years ago this year, once said “I love pictures almost as much as I love music.” He’s long been labeled an Impressionist, and his music has been almost inextricably connected in popular imagination with the paintings of Claude Monet. The label was not one that Debussy intended, according to Wunsch, nor is it an accurate representation of Debussy’s goals. “First, Debussy was not trying to imitate Impressionist painting,” Wunsch said, “and second, he did not have the same ideals as those painters.” Wunsch explained that while the Impressionist movement in art grew out of Realism, Debussy’s philosophy grew out of his attraction to other kinds of art, and the symbolist movement in literature, which strove to represent reality indirectly through metaphor and allusion. A particular attraction was the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé, author of L’après-midi d’une faune, the text that inspired one of Debussy’s most famous works.

Debussy was more directly influenced by the works of James McNeill Whistler, J. M. W. Turner, Diego Velázquez, and Japanese woodblock-print makers such as Hokusai. These artists, generally speaking, flattened perspective, enlarged the proportion of negative space, and limited their palettes to create works that are extremely nuanced, evocative, atmospheric, and fundamentally asymmetrical.

Debussy’s preludes are simultaneously colorful and monochromatic, and listening to any one of them brings these descriptors to mind. No wonder, Wunsch said, that Debussy once remarked that “a painting executed in gray is the true ideal.”

Perhaps the most monochromatic of painters was Whistler, now best known for his painting of his mother, but known during his lifetime more widely for a series of Nocturnes. Wunsch showed his Nocturne in Black and Gold—The Falling Rocket (1877), whose showers of gold paint distributed asymmetrically across a primarily black canvas were so disorienting that its initial exhibitors mistakenly hung it upside-down. Whistler was perhaps Debussy’s favorite contemporary painter, and this painting brings to mind both his final prelude, Feux d’artifice (Fireworks), and his orchestral triptych Nocturnes.

Another work that Debussy greatly admired was Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa from his 1830s series 36 Views of Mount Fuji (Monet was also an admirer and owned one of the original prints). Debussy used it on the cover of his 1905 orchestral work La Mer (The Sea). He also created a set of three pieces for piano solo in 1903—Estampes (Prints)—inspired in part by scenes in Japanese prints.

Wunsch was careful to mention, however, that the connections between music and specific works of art were probably not intended by Debussy to be explicit ones, but rather a manifestation of “shared aesthetic concerns.”

The performances themselves were each thoughtful and beautifully executed. This refreshing exploration of a great work and the milieu of its creation served as a model for artists who wish to make connections between their repertoire and other genres and disciplines, and one hopes that it represents the beginning of not only a series, but also a tradition of engagement and curiosity with even the most familiar works, that they may continue to remain fresh and surrender new secrets.