Title

Subhead

When the Juilliard School of Music launched a new Dance Division beginning with the 1951-52 academic year, the faculty included many of the era’s most illustrious and influential creative dance luminaries. Thanks to the visionary intentions of Martha Hill, the division’s founding (and longtime) director, ballet and modern dance were equally represented in the curriculum. Thus such leading lights of ballet as Antony Tudor, Jerome Robbins, and Agnes de Mille taught alongside José Limón, Doris Humphrey, and Martha Graham.

Martha Graham receiving the Ninth Annual Capezio Dance Award in 1960, presented by Juilliard President William Schuman on behalf of the award committee.

Antony Tudor rehearsing with dance student Sue Knapp in his Jardin aux Lilas, set to music by Chausson, in April 1967.

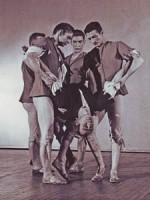

(Photo by Elizabeth Sawyer)José Limón (upside down) with men's group in his work There Is a Time.

(Photo by Photo by Arnold Eagle)Body

Three seminal, enduring works by three of those original faculty members will be seen side by side on Juilliard’s annual spring dance program this month, in distinct contrast to the division’s recent intense focus on original works. Lawrence Rhodes, the Dance Division’s current director, has titled the program—which offers pieces by Graham (1894-1991), Tudor (1908-87) and Limón (1908-72)—“Dance Masterworks of the 20th Century.” This is a statement of fact, not at all hyperbole. Representing three decades during which concert dance made impressive advances in seriousness, sophistication, and stature—the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s—these works have provided interpretive challenges to generations of dancers, while offering powerfully resonant experiences for generations of audiences. The program also celebrates the centennials of Limón and Tudor.

Tudor’s Dark Elegies, first performed by London’s Ballet Rambert in 1937, followed by one year his equally masterful Jardin aux Lilas (Lilac Garden), cementing his reputation—before the age of 30—as a supremely original and subtle choreographer who worked within the ballet vocabulary but achieved much of the expressive and psychological power of modern dance. His reputation—an exalted one, though based on relatively few ballets—is for revealing subtle emotional states and psychological insights through ballets that are “dramatic,” but in a streamlined, understated way.

Dark Elegies was one of very few Tudor works in which the dancers did not portray specific, identified characters. Set to Gustav Mahler’s poignant Kindertotenlieder (Songs on the Death of Children), it portrays a close-knit, unspecified community expressing and sharing its grief in the wake of tragedy. The five sections are all the more powerful for their pared-down, elemental expressions of sorrow, allowing the work to achieve a timeless universality that has ensured frequent revivals on ballet stages through seven decades.

Graham’s Appalachian Spring is undoubtedly the best-known work on the program. Not only is it one of her most beloved and frequently performed dances (even American Ballet Theater and the Joffrey Ballet have had a go at it), but the Aaron Copland score, which was commissioned specifically for Graham, has become one of the most celebrated and beloved 20th-century American compositions. Created in 1944, the year Graham turned 50, the work focuses on a newly married young couple launching their new life together in a frontier setting. Through four vividly drawn characters—the Bride, the Husbandman, the Revivalist, and the Pioneer Woman—and a charming cluster of four women who bob and flutter around the Revivalist, Graham evokes a rich range of possibilities: the robust, joyful anticipation of the young pair; fear of the unknown that lies ahead; the potentially sinister machinations of the preacher who holds sway in a community and the sensual powers he exerts on his followers; and the overview of experience and maturity of the stalwart, grounded woman who can offer guidance.

As universal as it has proved to be, Appalachian Spring was a very personal work for Graham. Erick Hawkins, who portrayed the Husbandman, was her lover (and later, very briefly, her husband) and her deep feelings for him enabled the middle-aged choreographer to portray the exuberant, youthful bride convincingly. (Hawkins went on to have his own substantial choreographic career, as did the dancer who created the role of the Revivalist—Merce Cunningham, then a member of Graham’s troupe before going on to become a seminal, boldly innovative 20th-century choreographer who continues to create major new works today.)

Reviewing the dance in The New York Herald Tribune in 1945, the noted critic Edwin Denby wrote, “Each character dominates the stage equally, each is an individual dramatic antagonist to the others. So the piece is no passionate monodrama of subjective experience but an objective conflict united in its theme.”

Limón’s 1956 There Is a Time, which had its premiere at Juilliard, takes inspiration for its structure from the Book of Ecclesiastes—the well-known passage that begins, “To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven.” At its core is a powerful communal momentum as, in between individual sections, the ensemble comes together, often returning to grand circular patterns. Limón shared with his teacher and mentor Doris Humphrey a deeply humanistic impulse for his dances, and There Is a Time surges with eloquently unsentimental human emotion. Reviewing its premiere in The Herald Tribune, Walter Terry wrote that the dance “communicates that rarest of theatrical achievements, spiritual luminosity. Limón has summoned forth some of the freshest—in form and in spirit—movement patterns he has ever placed upon a stage.”

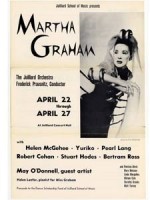

Busy as these three choreographers were, creating works, they also made time to teach. Tudor and Limón, in particular, were strong presences at Juilliard during the first two decades of the Dance Division. After the initial years, Graham was active more in an advisory capacity, but many leading members of her company were on the faculty. Yet the School did provide the stage for a crucial season for her company in April 1952. Graham had been offstage for a significant period, recovering from a knee injury, and without her central, volatile performing presence, her company had been mostly inactive. The six performances (of two programs) at Juilliard marked the troupe’s first New York appearances in two years, and included a brand-new work commissioned by the Juilliard School of Music, Canticle for Innocent Comedians.

This was one of the rare works in which Graham did not create a central role for herself, and it showcased such vivid company members as Yuriko, Bertram Ross, Helen McGehee, and Pearl Lang. Among the students peeking in and marveling at its rehearsals was Paul Taylor, then a new Juilliard student who had transferred in from Syracuse University—and now one of our country’s greatest and most prolific choreographers. “The whole dance was the loveliest, most impressive, most magical thing I’d ever seen,” he wrote in his autobiography, Private Domain (1987). In his all-important New York Times reviews of the 1952 programs, dance critic John Martin wrote that “the fallow period has manifestly given her new perspective and new strength” and that Graham “has returned to the field in great form, both as a performer and as a creator.”

Among Taylor’s recollections of Juilliard, where he was enrolled for one year, was receiving a “lesson in humility” from Tudor, who put him in his place in the midst of a party after the young dancer had become a little too full of himself. Tudor had a reputation as a figure of searing intensity and a master of the cutting remark. Professional dancers could be reduced to tears by his method of drawing out what he sought in their performances, so one wonders what young students encountered in his classes.

Two current members of Juilliard’s dance faculty were students there in the mid-’60s and vividly recall Tudor’s exacting ballet technique classes. Linda Kent, who also took those as well as his adagio (partnering) classes, recalls, “He was famous for leaving the woman on the left foot the whole time—you’d come out of class, and one shoe was always beaten to a pulp! He would do things like come over and ask, ‘What’s your left eyebrow doing?’” Asked about his penchant for asking dancers to plumb their depths and strip themselves bare emotionally, she said, “I think he wanted to get to the subtleties, but some of us needed more of the basics before we would be able to approach that.”

Laura Glenn, who took his technique class as a freshman (though generally students didn’t study with him until they were sophomores), notes, “For many people, he was intimidating. I dodged the bullet on that. I was alerted that, if you’re afraid of him, he could eat you alive. So I was smart enough to know I had to look him in the eyes. He was one of those people whose eyes twinkle—you can see when mischief is going on. He didn’t camouflage it. He had a very deep spiritual base, and a prodding playfulness. Some people he prodded hard and bad. But I can’t speak to that, because I got his good side.”

At the time he came to Juilliard, Tudor had left Ballet Theater, where he had helped shape the company’s identity during the 1940s. In between freelance projects for various major companies, he choreographed some works on the students or restaged earlier ones for them. In 1971 alone, at a time when he was choreographing infrequently, he created three works on the students, including the charming Continuo, set to Pachelbel’s Canon in D.

Limón, whose works were often featured at Dance Division performances, held students rapt with his innate nobility and commanding presence. “I was awed by him,” says Glenn. “He had a certain kind of carriage and a remoteness. He saw something large and magnificent in the world, and if you stood near, maybe you could get a glimpse of it. That was the feeling I had.” Glenn forged a strong connection with the Mexican-born choreographer early on, joining his company—where she performed for 11 years—after her sophomore year.

Kent, who became a standout performer with the companies of Alvin Ailey and then Paul Taylor, recalls Limón as “very iconic, to me, at that point. He would talk about how the body is an orchestra, and how you want to use the different parts of it to join together to make the whole.” In class, she recalls, “he would gesture with his hands all gnarled up and say, ‘Please, do not use the hands like fried clams’—that one has stuck with me. For me personally, I was struggling with Limón’s movement. It didn’t come as naturally to me. It’s scary. It was ‘go very off-center and then come back.’ I think I felt I didn’t have a strong enough center that I could just throw myself.”

Glenn was among the Juilliard students on whom Limón created two initial sections of what became the large-scale 1964 work A Choreographic Offering. They then went on to perform in the premiere of the full work later that summer at the American Dance Festival. Recalling that experience, Glenn says, “I kind of died and went to heaven. I remember thinking, even if I never do this again, it would be enough. It was such a powerful experience for me. I felt so alive doing his works. I had opportunities to go to other companies, but nothing was as large in spirit, as human, as delving into life.”

Recalls Glenn of the two towering figures who shaped her experience at Juilliard, “With Tudor, I always had a sense of his broader view. He made a large context for dance—that dance could contain life. For me, it was about being nourished by dance. Both of them were nourishing, and they served very different meals.”

Tudor, Graham, and Limón have all nourished generations of Juilliard dance students as teachers and mentors who offered inspiration and challenges. Many of their works have been featured on the School’s dance performances throughout the decades, and this month's program is certain to enhance that rich tradition.

The Antony Tudor Centennial Celebration, taking place on March 29 and 30 at Juilliard, will bring together generations of dancers and others to mark the great choreographer's 100th birthday. The weekend will include workshops reconstructing Tudor’s class combinations and choreography, as well as studio workshop performances by dancers from New York Theater Ballet, ABT II, and the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School at American Ballet Theater. A video historical archive of Tudor’s life and work will be created as participants share their memories and experiences of working with him. Dance critic Clive Barnes will moderate two panel discussions, the first with dancers Eliot Feld, Bonnie Mathis, Kevin McKenzie, Amanda McKerrow, Kathleen Moore, Kirk Peterson, and Lance Westergard, who will recall studying and performing with Tudor. A panel of writers and musicians will include Judith Chazin-Bennahum, Alex Ewing, Leo Kersley, Donald Mahler, Malcolm McCormack, Jane Pritchard, and Elizabeth Sawyer. The weekend is jointly presented by the Antony Tudor Ballet Trust and The Juilliard School. The complete schedule of events is available at www.antonytudorballettrust.org.