Column Name

Title

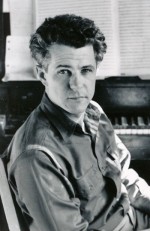

Composer and former faculty member Hugh Aitken (B.S. ’49, M.S. ’50, composition) died on December 24 at the age of 88. He is survived by his wife, Laura Tapia Aitken, and their children, Peter and Alexandra, two grandchildren, and one great grandchild.

Body

Born in New York City, Aitken studied violin with his father and piano with his grandmother before switching to clarinet. He enrolled at New York University as a chemistry major, but left to serve in the Army Air Corps in World War II as a B-17 navigator in Europe. In a 1987 interview with the Wyckoff (N.J.) News, Aitken said, “I told myself if I got through the war, I was going to study composition.” Juilliard didn’t have a composition major at the time, so he studied clarinet with Arthur Christmann; by the time he graduated, composition, which he studied with Vincent Persichetti, Bernard Wagenaar, and Robert Ward, was a major.

Aitken started teaching composition at Juilliard in 1951 and remained for two decades; he also taught Literature and Materials of Music. In 1970, he was hired to join what is now William Patterson University’s expanding music staff, where he served in numerous capacities, including as chairman, until his retirement, in 1996. Aitken, who received numerous high-profile prizes and commissions, composed more than 80 works, including two operas, three violin concertos, a large-scale oratorio called The Revelation of St. John the Divine, and 10 solo cantatas for voice and instruments. Among his commissions was “The Drunkard,” one of 13 variations by Juilliard composers on a theme written by then-president William Schuman for faculty member José Limón. It was performed here in April 1961.

In the 1987 News interview, Aitken talked about the challenges and rewards of a life in music. “Composing is hard work. It’s good when things come easily but agony is not too strong a word to describe the difficulty when things don’t work out,” he said. “You don’t go into music to become wealthy. Indeed, genteel poverty is a fact of life for many in music. But I consider it absolutely wonderful, surprising, and even outlandish that I have been able to … get paid for doing something that I absolutely love to do.”