Title

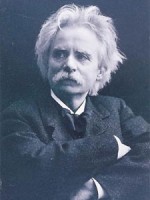

This year marks the centennial of the death of Edvard Grieg, one of the great 19th-century nationalistic composers. One hundred years ago, he was considered a major power among European composers, with his art songs and piano cycles being frequently performed. Grieg was not only a composer, but also a conductor, pianist, writer, and humanist. He himself once said, “One must first be a human being. All true art grows out of that which is distinctively human.”

Body

Born in Bergen, Norway, in 1843, Grieg began studying piano with his mother at 6 before attending the Leipzig Conservatory at 15 to study piano with Louis Plaidy. Upon finding Plaidy’s approach too traditional, Grieg switched teachers and began studying with E.F. Wenzel, one of Schumann’s close friends. Under this new instruction, Grieg was able to explore his individuality and unique talents. In his last year at the conservatory, Grieg studied composition with Carl Reinecke. His early compositional style was heavily influenced by German and Danish composers such as Mozart, Schumann, and Niels Gade. But when he reached his early 20s, Grieg realized that his compositions were paying homage to styles of other countries while neglecting his own Norway. He moved from Leipzig to Denmark, where he stayed with the famous Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, getting some of his first exposure to Norwegian folk music. He also met Rikard Nordraak, a young composer who wrote the Norwegian National Anthem and was known for his use of Norwegian folk idioms. When Nordraak died at age 24 in 1866, Grieg was so devastated that he composed his Funeral March in Nordraak’s memory. It is said that later in life, Grieg carried a score of this piece in his pocket, just in case.

Grieg studied Norwegian dances, plays, poetry, novels, and songs, as he developed his own style of composition. His use of parallelism, pedal points in the bass, and chromatic melodies that followed rules of functional harmony were qualities associated with his music. (Parallelism can be found in French Impressionist music, showing Grieg’s influence on Maurice Ravel and Claude Debussy.) Grieg also studied Norwegian instruments, such as the country’s national folk instrument called the Hardanger fiddle, and he incorporated some folk tunes written for this instrument into his compositions. (The opening phrase of “Morning” from his Peer Gynt Suite is widely believed to come from the tuning of the sympathetic strings of this fiddle.) Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, Op. 16, shows the influence of the Hardanger folk tune called “Fanitullen” (and also has the same form and key as Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, not surprising when you recall that he studied with one of Schumann’s friends). According to L. Michael Griffel, who chairs the Music History Department at Juilliard, “Grieg developed a personal style that came to define Norwegian art music.”

One of the first important nationalistic composers from an area that had not yet dominated the music scene, Grieg influenced other composers incorporating folk idioms such as the Hungarian Bela Bartok and the Romanian George Enescu. He was also a model for composers who were moving away from the Romantic German style. Percy Grainger and Frederick Delius followed Grieg in finding new ways to connect chords, harmonize tunes, and change keys. Grieg’s work—along with other Norwegian artists such as playwright Henrik Ibsen, writer Bjornstjerne Bjornson, and painter Edvard Munch—promoted national consciousness, and helped pave the way to Norway’s independence in 1905.

In 1885, Grieg settled in Bergen with his wife, Nina, building a Swiss Victorian style house called Troldhaugen, with a composer’s hut in which he could work undisturbed. Whenever he left the house, he put a note in the hut asking possible intruders not to disturb the papers because they would not be valuable to anyone but himself. Some 30 years after his death in 1907, the entire estate became a museum that is one of the great tourist attractions of Norway.

“His music was a reflection of the environment in which he lived: Nature, light, blue waters, glaciers, mountains, and fjords,” says Juilliard faculty member Per Brevig, who founded the Edvard Grieg Society in 1991 and will conduct the Grieg Festival Orchestra on December 9 at 2:30 p.m. at Zankel Hall in a program honoring the composer’s centennial year. Brevig, who has been a champion of Grieg’s music for many years, adds that his own interpretations have been influenced by hearing the composer himself perform on piano rolls. “I heard him play ‘Butterfly,’ a short piece that was performed with spirit, rubato—and fast,” he recalls. “It influenced my interpretation of Grieg’s music even when I conduct his orchestra music.”