Column Name

Title

“Art and China’s Revolution,” which opened on September 5 at New York City’s Asia Society, is a roller coaster of a show, alternately exhilarating, exciting, and devastating. The first major exhibition to deal with the three decades after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, it focuses on China’s Cultural Revolution. It comprises large-scale oil and ink paintings, sculptures, drawings, artist sketchbooks, woodblock prints, posters, and objects from everyday life, as well as a few video documentaries.

Ceramic teapot and matching cup with scene from revolutionary ballet The White-haired Girl, Battledore Collection (Photo by Nancy S. Donskoj)

Xu Bing, untitled, with the inscription, "Little Lixin at the age of seven and a half," 1975 (pencil on paper), collection of Xu Bing (Photo by Xu Bing Studio)

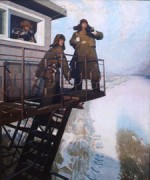

Shen Jiawei, Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland, 1974 (oil on canvas) (Photo Courtesy of Shen Jiawei)

Body

The show manages to capture the energy and optimism—as well as the ultimately shattered dreams—of young people at a pivotal time in their nation’s history. Ironically, the very nature of the frenetic excitement during that time may have led to the excesses of the Red Guard and the destruction of these dreams. Certainly one goal was achieved, to which many artists would aspire: the breakdown of “high” and “low” art. For example, the most famous picture of the period, Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan (1967), painted by Liu Chunhua, was reproduced on nearly one billion posters.

Although this image and other propaganda pictures of the early 1970s are most familiar to viewers, the show also features works by artists who went against the prevailing style. One group, a younger generation of contemporary artists, included the artist Xu Bing, who today has attained international success. As one of millions of youths sent to the countryside for agrarian re-education, he has said that he enjoyed living among “people transcending politics, hierarchy, and class.” The sensitive portraits in the show illustrate his feelings. There was also an underground movement called the No Name Group, whose members secretly sketched conventional landscapes, forbidden at the time. By striving to capture the varied artistic ramifications of this political turmoil, the exhibition demonstrates, as the co-curator, Melissa Chiu, said, that there is “no one story” told here.

Although the current Chinese government had originally agreed to lend nearly 100 works, it eventually backed out. It has been suggested that the timing of the exhibition’s opening was too close to the Beijing Olympics. But Vishakha N. Desai, the Asia Society’s president, says, “It has more to do with China’s desire and aspiration to be seen in a new light. This is a time for celebration. They don’t want to be reminded of a difficult past.”

Despite the Chinese government’s decision, the Asia Society decided to proceed with the show, seeking loans from private collectors. “Even though this is a period many would prefer to forget, it is nevertheless one that produced a visual culture that continues to permeate contemporary Chinese art,” explains Zheng Shengtian, co-curator with Ms. Chiu, in a news release. Mr. Zheng himself was an artist and teacher at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art) during the period covered by the show. Critical of the Red Guards for their violence and destruction of cultural artifacts in 1966, he was imprisoned with other artists, and forced to participate in self-criticism sessions.

I had a number of expectations for the show. Enlightenment and education headed the list—so I was amazed to find myself exhilarated and elated. The undeniable triumph of the human spirit is here demonstrated by artists who felt compelled to make art even during the most troubling of times. The presence of some of these artists at the press preview, explaining their work and ideas, made the excitement palpable. I had known that this work would be interesting as propaganda, but how would it come across as art?

A short discussion of how some of the artists view their works today might be illuminating in this regard. Shen Jiawei (b. 1948), author of one of the essays in the catalog, considers his large oil painting Standing Guard for Our Great Motherland (1974) his most valuable possession. Though the Cultural Revolution, launched in 1966, ended his dreams of going to art school, at the same time it paradoxically enabled him to be a painter and achieve fame at an early age. A mostly self-taught artist, Mr. Shen spent time in the countryside and was thrilled to have been, at age 26, among a select few chosen from millions, and considered a “worker or laborer artist.” The romanticism, high drama, contrast, and perspective embodied in his work are remarkable for someone deprived of standard art school education. He and Han Xin (b. 1955), whose painting was influenced more by French Impressionists and who was considered a rebel and part of the No Name Group, both spoke of the artist Chen Yifei (1946-2005) with tremendous reverence and awe. Chen’s iconic painting Eulogy of the Yellow River, like Shen’s, shows an ordinary Chinese soldier happily standing guard with his rifle in a mountain landscape. Both the more accepted Shen and the rebel Han agreed that they and other Chinese painters were greatly influenced by Chen Yifei. Indeed, Han was personally involved in “rescuing” the work from destruction.

I never envisioned such an exhibition happening in New York City when I first traveled to China in 1986. I also never thought I would see the day when a contemporary Chinese painting would sell for more than $6 million. A few years ago, Sotheby’s did not even hold auctions of Chinese contemporary art. But last year it sold nearly $200 million worth of Asian contemporary art, most of it by Chinese artists.

In the October 1986 Juilliard Journal, I wrote an article titled “From Mao to Modern Art (With Apologies to Isaac Stern),” in which I reported on the lectures I gave that summer at Beijing’s Central Academy of Art. These had been requested by several professors there, who wanted me to present a whole history of Western art in two one-hour sessions. I sensed that the students were bored, even annoyed, by my first lecture. Fortunately, a young art-history student who translated for me told me the truth: “They know all that,” he said; “they want to know what’s happening now!” So I put aside my prepared notes and instead drew maps of uptown and downtown art scenes in New York. Now the students showed excitement and enthusiasm, many of them inviting me to see their own work. They were proud that they had rebelled against old rules, making oil paintings of nudes, reminiscent of what American artists made in the early part of the 20th century. At the time, I didn’t understand how this was “modern”—but now, more than 20 years later, it all makes perfect sense. In fact, one of the artists in this show at the Asia Society, himself a student at the Beijing Central Academy four years before I gave my lectures, completed my sentence before I could, when I told him the students weren’t interested; he jumped in and said, “They wanted to know what was happening now!”

As Melissa Chiu points out, this exhibition is “a project that you couldn’t stage in China. It sheds light on a period of time that now seems to be forgotten.”

Do check the Web site, www.AsiaSociety.org, for the many lectures, films, and concerts being held during the exhibition, which runs through January 11. The Asia Society is at 725 Park Ave (at 70th Street).