Column Name

Title

Paradoxically, the current exhibition of sixth-century Chinese Buddhist cave sculpture at the N.Y.U. Institute for the Study of the Ancient World allows us to witness something startlingly new. “Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan” (pronounced “shahng-tahng-shahn”) uses digital technology to virtually reassemble a renowned Buddhist cave temple whose sculptures had long ago been looted and dispersed all over the world. This installation invites us to experience the breathtakingly moving sculptures in the manner in which their makers meant us to—in their original setting.

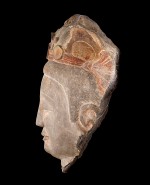

Head of a Bodhisattva Attendant of Maitreya (550-559 A.D.), limestone high relief with traces of pigment, 33 1/16 in. x 14 in. x 16 15/16 in.

(Photo by University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology)Hand of Maitreya, Buddha of the Future, Holding the Looped End of His Robe (550-559 A.D.), limestone high relief, 29 in. x 16 1/2 in. x 11 in.

Body

These Northern Qi dynasty (550-577 A.D.) caves were carved into the side of Xiangtangshan (Mountain of Echoing Halls). Wealthy Buddhist patrons, probably emperors and courtiers of mixed ethnic, non-Chinese background, sponsored them in hopes of ensuring blessings for their families on earth and a happy afterlife. Their motivations in doing this were not unlike those of donors of cathedrals and altarpieces in the Middle Ages.

The caves were part of a long tradition begun in India of carving holy places into the earth. Such caves originally housed monastic communities and often provided places of worship for the devout to visit. Most of them were filled with sculpture and paintings illustrating a set iconographic program. The one in this exhibit tells of the Buddha of the past, present, and future. These larger-than-life sculptures embodying physical presence and spiritual strength enabled worshippers to visualize Buddhist goals and precepts.

Many cave complexes were created in China during different dynasties, some along the Silk Road. I was privileged to visit a number of them on a trip through China several years ago. One often has to climb steep precipices in order to reach them. Before entering the cave, one might observe a framework of temple and scaffolding on the mountain’s surface. Then, climbing the steps, one ascends into the aeries. The less accessible the cave, the less likely it was to suffer plundering of precious objects. Although the virtual cave cannot reproduce the thrill of sheer cliffs reconstruct them.

After immersing yourself in the virtual cave, you can visit about a dozen of the original stone sculptures in a separate room. Each is important, and powerful in its own right, but once you have seen the whole, you will have a much greater appreciation of the parts.

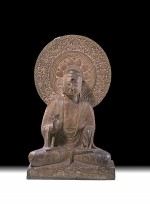

Probably the most impressive single sculpture is a limestone Seated Buddha. A sumptuous and intricate mandala or halo surrounds the head of this simply carved, rhythmically draped figure. Swirls encircle flower buds enclosing jewel-like objects. Naturalism fuses with abstract design. Human artistry evokes sun, light, nature, and enlightenment, setting off the earthly from the divine.

Another sculpture, the Head of a Bodhisattva Attendant of Maitreya, represents a follower of the Buddha of the future and displays influences from Central Asian traders with its intricate crown and sensitive carving. The curators have placed it near the Standing Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guanyin), which gives us an idea of how the Maitreya bodhisattva head might have looked if it were still attached to a body (and not long ago vandalized). These sorts of bodhisattvas (followers) became some of the most popular Buddhist images since they embody the possibility for all to attain enlightenment in this world. They are merciful deities, believed to help those in need. Freestanding, these are also more lifelike than previous depictions of the bodhisattva, and thus more accessible.

The gigantic Left Hand of Maitreya, Buddha of the Future, Holding the Looped End of His Robe comes from a Buddha on the central pillar of the north cave. It was photographed in the early 1920s with this hand still in place. Although Buddhists believe the hand possesses an innate power and majesty (as did Michelangelo and Rodin), the sculptors did not mean for this one to be severed from the rest of the body—that too was a theft.

You can’t look at these works of art without asking what makes them great. The artists created them to express and attain spiritual and religious beliefs; art and artisanship were not primary goals. Or were they? Perhaps these aspects cannot be separated.

Indeed, looking at them reminded me of some observations Murray Perahia made in a recent master class at Juilliard (see article on Page 1). He called Beethoven’s Sonata No. 30 in E Major, Op. 109, a “spiritual message, a plea for peace,” though he added that “only through strength and conflict” can one achieve peace. Perahia also pointed out that the Sonata No. 27 in E Minor, Op. 90, concerns love and mortality, comparing it to Shakespeare’s love sonnets. In a poignant passage, he noted, Beethoven’s music asks “Must we die?”

Such thoughts may seem unrelated; however, I believe that in order to be truly great, works of art need to ask these questions. No matter what the medium, by combining beauty, art, and intrinsic meaning, such great works teach us something about life and death.

The monumental Buddhist cave sculptures rise to such heights. They teach and enhance our lives by means of craftsmanship, beauty, and delicacy, but above all, they possess an ineffable strength and spirituality.