Column Name

Title

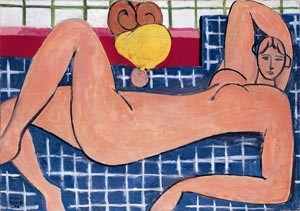

Henri Matisse, Large Reclining Nude, 1935. Oil on canvas. The Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collection. ©2011 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

(Photo by Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society ) More Photos »The Jewish Museum’s current exhibition, “Collecting Matisse and Modern Masters: The Cone Sisters of Baltimore,” which continues through September 25, is well worth seeing. As the museum’s director, Joan Rosenbaum, points out in her introduction to the catalog, the show’s goal is to illuminate aspects of Jewish culture and art history through an account of the collecting skills of two visionary American Jewish women in the early part of the 20th century. It fulfills these aims admirably, and is the latest in a series of exhibitions at the museum dedicated to the accomplishments of women.

Body

The show’s curator, Karen Levitov, notes in the catalog that the Cone sisters were a part of the intelligentsia of their times, and stresses their education, wit, and prescience. Nonetheless, every review and article I have seen about this show begins with a statement about how surprising it is that these two “buttoned-up spinsters” were so avant-garde in their artistic tastes. Matisse called them his “two Baltimore ladies.” Gertrude Stein at one point pejoratively called the sisters “shoppers.” But to continue to refer to them in this manner, as even this show and the film that accompanies it repeatedly do, is to perform a disservice. Where is the equivalent of “spinster” or “shopper” used for male collectors? These powerful, intelligent women, filled as they were with life, vitality, curiosity, and a thirst for travel and adventure, had a vision.

The film and some remarks in the acoustaguide acknowledge that the two remarkable Cone sisters, Claribel (1864–1929) and Etta (1870–1949), were both lesbians. Contrary to the clichéd image of the spinster as a woman who is desperate for a man, neither sister sought marriage, and indeed, Etta rejected a marriage proposal from the sculptor Mahonri Young in 1905, finding him uninteresting. Instead of disparaging the sisters, we should begin by expressing our admiration for their accomplishments.

The facts are that Claribel Cone became an M.D. in 1890, a time when very few Jews, much less Jewish women, achieved this vaunted distinction; and Etta Cone, a talented pianist, and capable manager of the family household, more than likely had a love affair with Gertrude Stein! Claribel became a pathologist, working in the pathology lab at Johns Hopkins, teaching, and collaborating with European researchers for more than 20 years. Together the sisters held “at homes” in Baltimore that attracted Stein, her brother Leo, and numerous artists, writers, scientists, and musicians. These gatherings preceded, and, doubtless set an example for, the Steins’ acclaimed Paris salons in the years leading up to World War I.

Claribel and Etta Cone bought Fauve paintings at a time when the press only ridiculed this kind of art. According to his grandson, Matisse himself has been quoted as saying that it took even more gall to purchase them than to paint them. The sisters then went on to collect paintings by Picasso, Cézanne, and many modern masters long before these artists achieved fame and recognition.

The present exhibition is most interesting in acquainting us with the history and circumstances of the acquisition of modern works of art during the early part of the 20th century. However, it should not seem so very startling that two independent, forward-looking, ambitious young women were attracted to modernism. Aided by considerable wealth, they traveled together to Europe annually, buying not only paintings and sculpture, but also art books, textiles, and jewelry.

Now we know why the two sisters—hardly prudes—may have appeared buttoned-up—and eccentric—in their day. Claribel’s pursuit of medicine was considered unladylike in her social circle, and both sisters were unflatteringly caricatured, undoubtedly by people who were envious of their wealth and possessions.

The art in the small exhibition is very good, but mostly not spectacular. Not surprisingly, the sisters had a taste for beautiful women. The standout painting in the show is Matisse’s Large Reclining Nude, acquired by Etta Cone in 1935. She bought it after the master had sent her 22 photographs documenting how he had worked and reworked the painting. Etta hung it in Claribel’s apartment (after the latter’s death) opposite the controversial Blue Nude, created 30 years earlier. In context, the works of art must have looked incredible, complementing each other, and surrounded by furniture, textiles, and other works of art. The show has a number of charming and beautiful drawings and paintings by the likes of Matisse, Picasso, Van Gogh, Gauguin, etc., but you won’t really get a sense of the importance of the Cone collection unless you visit the Baltimore Museum where the bulk of the work remains.

The reason to go see this exhibit is to try to understand the phenomenon of two women who broke the mold during the first half of the 20th century. The photos of the sisters are wonderful, as are the artifacts. We get to see letters from Matisse, Picasso, the Steins, and others to each sister, as well as notes written between the two. There are also numerous diary entries and archival items. Jewelry and textiles that the women collected during their travels are included. In their integration of textile, fabric, painting, and sculpture collecting, they acted as Matisse himself did. Rather than thinking of the paintings as separate, they considered them to be an essential part of the decor of their apartments. The everyday context is shown to be vitally important to them.

The small size and scope of the exhibition encourage intimacy and comprehension. Go to it to gain an understanding of collecting and of two remarkable collectors. As I mentioned, though, one needs to travel to Baltimore to see the incredible collection itself. There the Cone collection numbers around 3,000 objects, is considered the crown jewel of the museum, and includes 500 works by Matisse. The sisters bequeathed their artworks to the Baltimore Museum on the condition, stipulated by Claribel in her will, that “the spirit of appreciation of modern art in Baltimore becomes improved.”

The sisters more than achieved this goal. The spirit of appreciation of modern art was improved not only in Baltimore, but also in the rest of the United States, largely due to the Cones’ pioneering efforts and foresight.