Column Name

Title

Subhead

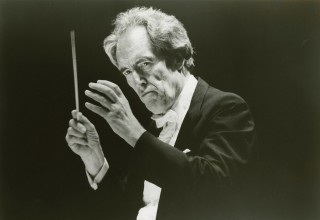

Otto-Werner Mueller was Juilliard's director of orchestral studies and head of the conducting program.

(Photo by Steve Sherman)Otto-Werner Mueller, who was Juilliard’s director of orchestral studies and head of the conducting program (1987-2004; he retired from the faculty in 2005), died on February 25. He was 89 and is survived by his wife, former Juilliard associate dean Virginia Allen; sons Bernie, Michael, and Peter; grandchildren Christina, Peter, and Sophie; and a brother, nephew, and niece. Jens Georg Bachmann (Advanced Certificate ’99, orchestral conducting), who came to Juilliard to study with Mueller, wrote about his mentor.

Body

The music world lost one of its most influencial and pre-eminent teachers, educators, and artists with the death of Otto-Werner Mueller. Born in 1926 in Bensheim, Germany, a picturesque town near Frankfurt, Mueller studied from ages 13 to 18 at an elite music school in Frankfurt, where Richard Strauss occasionally came to teach, a formative experience for Mueller. After having positions with Radio Stuttgart and the Heidelberg Opera, Mueller and his first wife, Marga (Maragethe Burchart Mueller, a singing teacher to whom he was married for 56 years until her death), emigrated to Canada in 1951, where he did work for the Canadian Broadcasting Company and taught at conservatories in Montreal and Victoria. He also built a friendship with conductor Igor Markevitch, who became a mentor. The Muellers relocated to the U.S. in 1967, and he taught at, among others, Yale School of Music (1973-87), Curtis Institute of Music (1986-2013), and Juilliard while also guest conducting around the world.

During my conducting studies in my hometown, Berlin, I approached Kurt Masur, then the music director of both the Gewandhausorchester and the New York Philharmonic, to ask what would be the best place to finish my studies. He briskly replied, “Go to New York; Mueller is the right man! ” Little did I know that I’d have to undergo a three-to-four round, two-day audition ordeal to earn my new master’s approval, but I did, and the experience of working with him turned out to be pivotal.

At over six feet tall, Mueller was a towering authority as a person and teacher. His profound knowledge about every aspect of any musical work was comprehensive and holistic. Twice a week, he trained his few conducting students in the art of score analysis in private sessions at his home. “You have to learn how to study,” he said. He taught us the most profound way of unlocking the musical structure, accessing the entirety of a work in order to serve and reveal its intrinsic musical expression, emotional meaning, and content—the keys to the conductor’s (if not every performer’s) task. Only then were we allowed to step in front of the Lab Orchestra, where he fostered an atmosphere of veneration, humor, and fear. His musical critique, conveyed in a delicious rhetorical mixture of encouragement, reproach, unambiguity, and shouted commands (“careful!” was his trademark battle cry) reached not only his student conductors but also far into the orchestra. As he trained us, we were constant witnesses to and participants in his amazing orchestra-building process. Quality of sound and adherence to dynamics were supreme to him. “Ultimately,” he said, “the work has to emerge in front of the performer and listener like a grand architecture.” Some of the instrumentalists confided to us that they learned more about music in his rehearsals than in any other class.

After one lesson, he asked if I would go food shopping with him. Did I have a choice? The taxi took us to the German deli Schaller & Weber on the Upper East Side. He shopped extensively, showing me his favorites and watching the staff carefully while they weighed his selections, challenging them in German with his Hessian accent. On the way back, he told the taxi driver exactly where to make turns as he had the most efficient crosstown trip completely mapped out in his mind—life was a living structure for him.

Once, on the occasion of a Juilliard Lab Orchestra’s concertmaster’s birthday, the orchestra played “Happy Birthday To You” before tuning. Mueller stormed to the podium. An admonition about the use (or misuse) of our musicality (or lack thereof) was followed by instructions how to bow and phrase the song correctly: two hooked upbows on the upbeat as well as toward the downbeat of bar two so the “emphasis would land on the right syllable,” as he put it, climaxing in the fermata-held appoggiatura in the third-last bar—there was not a sound in his world that wasn’t analyzable and, consequently, more meaningful.

Sometimes brutally honest (especially for today’s politically correct world) and set in his ways and his uncompromising standards, Mueller embodied an artistic integrity and depth that were exemplary and unsurpassed. His authenticity made up his pedagogical and artistic singularity.

After one month at Juilliard, I received an emergency call from my family with the news that my father was dying. I choked down my tears and called my new teacher’s private number for the first time. His response couldn‘t have been more humane: He released me from lessons to go to Berlin, and said, “Remember, don’t be sad that someone is leaving, but be grateful that he has been with you.” This advice now applies to all of us whose lives he touched and changed forever.

Want to share your memories of Mueller? Let us know at journal@juilliard.edu.