Title

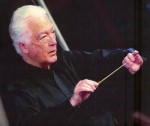

Renowned Australian conductor Richard Bonynge, a major force in shaping several of the great vocal careers of the late 20th century and a crusading specialist responsible for major revivals in the bel canto and French Romantic repertory, will give his first-ever New York City master class at Juilliard on October 9.

Body

The public master class will be the culmination of a weeklong residency sponsored by the George Solti Accademia in Tuscany; earlier in the week, Bonynge will work one-on-one with all the participants. The focus of the residency, according to Brian Zeger, artistic director of the Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts, will be the repertoire Bonynge has focused on throughout his varied career, particularly bel canto, which, Zeger said, “is so essential to young singers.”

Bonynge made his conducting debut in in 1962 with Rome’s Saint Cecelia Orchestra and since then has appeared in virtually all the world’s major houses including 25 years (1966-91) at the Metropolitan Opera, where he led works by Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Mozart, Gluck, Verdi, Offenbach, and Massenet—including the 1976 company premiere of Esclarmonde, just one of the rare and neglected works he has helped the world re-evaluate.

Though Bonynge has accrued all sorts of honors over the course of his storied career—he’s also served as the artistic director of the Vancouver Opera and musical director of the Australian Opera, among other administrative posts—the maestro turns out to be delightfully informal in an August phone interview with The Journal. “First off, don’t call me Sir Richard!” he said. “I have the equivalent honor, but we Australians don’t hold with those kinds of titles.”

While he frequently adjudicates competitions for both singers and conductors, Bonynge finds master classes very different in focus, tone, and content. Ideally, he feels, they shouldn’t have the element of competition. “I have no set rules. I like singers (if they’re good!) and try to relax them. I’m not there for the audience but for the singers, to see what they can learn in a few hours. I am not a voice teacher per se, but might make note of a few things if they come up,” Bonynge said. Still, he added, “One has to be tough. I’m not going to tell the students they’re lovely if they’re not—that doesn’t do anyone any favors! If I can help them, I will. But they have to be open to suggestion.”

He started doing master classes about 15 years ago, at the Pears-Britten School in Aldeburgh, England. The Juilliard residency is being funded by the Solti Accademia, which provides in-depth training and interaction with major operatic professionals for a dozen rigorously chosen students each summer. Bonynge has said of the academy that it’s “one of the few organizations in the world today that is teaching the true values of musical style.” With the Juilliard students, he’ll probably follow his usual pattern of working on matters of interpretation—“timing and delivery of recits, phrasing, how to present the music. Sometimes students just blast away at the public, perhaps thinking to impress. Don’t yell! I try and get young singers to take an overall view of a piece,” Bonynge said in the interview. “Certainly I can help most in bel canto or French literature, just because I have so much experience in it—I might not have that much useful to say about, say, Wagner, or modern opera. The bel canto style is much more fashionable among students now, but often they don’t realize that they really have to study it to make it happen,” he added.

Bonynge has a long history of working with singers, most notably superstar soprano Joan Sutherland, whom he married in 1954 after serving as her accompanist; the two would go on to make a large number of historic recordings together (Sutherland died in 2010). It was after meeting her that Bonynge developed his interest in researching the bel canto repertoire. He would also play a key role in the development in many other major vocal careers, including most spectacularly those of Marilyn Horne, Luciano Pavarotti, and Sumi Jo. While he continues to lead opera and concert performances around the world, Bonynge has also assembled and spearheaded a vast array of audio and video recordings, largely but not exclusively of operatic and balletic literature; his current projects include bel canto arias with soprano Elena Xanthoudakis, Massenet songs, and Kalman’s 1921 operetta Die Bajadere.

As he presides over master classes, Bonynge noted, “I hear a lot of Callas imitators, Sutherland imitators, and so forth. I encourage students to listen to recordings, but just for a point of view—to be familiar with them, but never to copy them. The goal is not to sound like somebody else; the longer you can keep the individual quality of your voice, you’re much more likely to make a career. I’m very anti-homogeneity!”