Column Name

Title

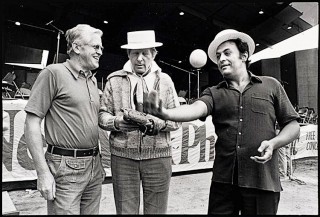

In this New York Philharmonic photo from the 1980s, Walter Rosenberger (left) has an offstage moment with actor Danny Kaye (center) and then-Phil music director Zubin Mehta.

(Photo by Courtesy of the New York Philharmonic Archives)Percussionist Walter E. Rosenberger (Diploma ’41), who was with the New York Philharmonic for 39 years and a member of the Juilliard faculty for six, died on July 27 in Wernersville, Pa. He was 94 and would have celebrated his 63rd wedding anniversary in August. He’s survived by his wife, Binny Mittlacher Rosenberger, two daughters, four grandchildren, and two great grandchildren.

Body

Rosenberger was born in Rochester, Pa., and started playing drums at 8, three years later joining the local high school band. After graduating from Juilliard, where he studied with Edward Montray and Saul Goodman, he joined the Pittsburgh Symphony and then the Army Special Services during World War II. Following the war, he joined the New York Philharmonic, where he served as principal percussionist from 1972 until his retirement, in 1985. Rosenberger gave private lessons and taught at Mannes and the Manhattan School of Music; he was also on the Juilliard faculty for six years in the 1980s. Faculty member Daniel Druckman remembers his mentor and colleague.

We all called him coach: the members of the percussion section, the stage crew, the other musicians in the orchestra, even students. Nominally, because he was the founder, player-manager, and inspirational leader of the New York Philharmonic Penguins, one of the metropolitan area’s least successful sports franchises. More importantly, because he embodied the word: a natural leader, a mentor, a teacher, and a guide. That he could do this with such effortless, self-effacing grace, and good will was a testament to his particular talents.

Leading the percussion section in the world’s busiest orchestra requires a specific skill set. Walter’s encyclopedic knowledge of the repertoire, his uncanny memory, and his attention to detail were the stuff of legends. His playing was always intelligent, informed, and exquisitely phrased. He was always aware of who he was playing with and how they would approach a specific passage. He instinctively knew which instrument to choose for a particular moment, which stick to choose, what sound a particular conductor wanted, and shared this knowledge willingly. But equally important were his social skills; his ability to interact positively and effectively with everyone around him—stage crew, conductors and soloists, composers, arrangers, extra players, other members of the orchestra—was unparalleled in my experience.

Walter was a consummate professional: intelligent, pragmatic, quick-witted, and kind. His smile, humor, and humanity are the things that stand out the most in my mind. He had a disarming inclusivity, a natural way of making everyone feel comfortable and qualified and worthy, which really brought out the best in all of us.