Column Name

Title

The glowing, gorgeous, sumptuous, and varied exhibition called Iran Modern at the Asia Society is no ordinary show. A recent New York Times review praised it for being “terrifically good-looking,” but also “threaded through with human drama and composed of work that is … cosmopolitan.” The exhibit focuses on three decades in Iran, ending with the 1979 revolution.

Through January 5 at the Asia Society Museum, 725 Park Avenue, at 70th Street

Ardeshir Mohassess, Untitled (1978), ink on paper, 17 x 12 1/12 inches

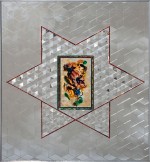

(Photo by Katayoun Beglari-Scarlet and Peter Scarlet Collection)Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian; Untitled (c. 1975-76); mirror, reverse-glass painting, plaster, and wood; 31 1/2 x 27 1/2 inches

Body

Today, when relations with Iran have been strained to the limit, this thoughtful exhibition comes like a sigh of relief. Indeed, it makes me wonder whether we might be capable of easing political tensions between nations by means of the arts. Some at Juilliard have certainly been attempting musical diplomacy. Cultures in Harmony, which William Harvey (M.M. ’06, violin) founded to use music to bridge cultural and national barriers, is just one example.

In regard to the visual arts, shockingly few American art historians have even acknowledged until lately that such a thing as Modernism existed outside the West. The question is why are they now?

In this postcolonial era, art pundits, like those in other arenas, have been forced to include a new emphasis and awareness of globalization. Geographical areas such as Africa, the Middle East, and Asia that were previously marginalized or ignored have now come to the forefront, and we have learned that, contrary to our previous beliefs, Europe and the United States did not “own” Modern art. Up until recently, many U.S. museums didn’t even identify artists from regions outside Europe and the U.S. by name but rather gave them generic “ethnic” recognition if they gave them any acknowledgement at all.

Many of us have forgotten (if we ever knew) that Teheran had become an important cosmopolitan destination prior to the 1979 revolution. Artists there studied and exhibited abroad. They participated in the Venice Biennale, and their works belong to collections ranging from New York’s Museum of Modern Art and N.Y.U.’s Grey Gallery to the Tate Collection—these are exceptions, though, as not many Western museums collected them. Still, this abundance allowed the Asia Society curators to borrow all but one of the more than 100 pieces in the present show from collections outside the country.

I had the great opportunity of walking through the show with one of the curators, Fereshteh Daftari, a native-born Iranian. She knew almost all of the artists personally and was able to give deep insight into their work as well as into the organization of the show.

She and her fellow curator, Layla S. Diba, organized the exhibit thematically into four sections. Saqqakhaneh (which refers to a 1960s and ’70s movement described below), Abstraction and Modernism, Calligraphy and Modernism, and Politics and Iranian Modern Artists. There is also an archive room, which provides background and documentation of the history, politics, and culture of the region.

Daftari emphasized to me that she sought to make a kind of mini-retrospective of artists within each section; she didn’t want a huge survey in which individual artists would become lost.

We began on the second floor with Untitled (Forms in Movement), a large white sculpture by Mohsen Vaziri-Moqaddam (b. 1924). The innovative 1970 wood and metal piece was meant to be interactive, that is, viewers could manipulate its parts. Unfortunately, due to its fragile nature, this cannot be done at present although there’s a video on AsiaSociety.org that shows how it works. This piece, like Vaziri’s sand paintings, recalls prehistoric creatures and times. They also look ahead to participatory and earth works.

Saqqakhaneh, Daftari told me, was a term invented to describe Iranian artists who, though greatly influenced by the School of Paris and other Western Modernist painters during the ’60s and ’70s, used popular culture motifs and seventh-century Shiite martyrs to avoid directly imitating Western works. Saqqakhaneh’s most important exponent, Parviz Tanavoli (b. 1937), is represented here by several imaginative, original sculptures and paintings, some of which feature calligraphy and pre-Islamic imagery and some of which are humorous or ironic. For example, his bronzes Prophet and Poet are both self-portraits in invented “calligraphy” on bronze. Since Islam forbids icons, the use of calligraphy to make portraits is in itself subversive. Oh, Persepolis, a bronze bas-relief covered with “calligraphy” (again, Tanavoli’s make-believe kind), can be seen as both proclaiming the wonder and glory of the ancient Persian city and also as a critique of over-glorification. I loved Charles Hossein Zenderoudi’s (b. 1937) storyboard linocut Who Is This Hossein the World Is Crazy About? The title is a pun on the artist’s name as well as a political critique of an Iranian imam. During the ’70s, Zenderoudi, who lived in Paris, was considered one of the world’s important Modernist painters. This shows that some of the Modernist Iranian artists did achieve recognition during the ’70s, but most have been forgotten since then.

Many of the works in the show are rebellious, but not in an obvious way—they can be perceived as critical and humorous. For example, several of Tanavoli’s sculptures, which are in the Politics section, are collectively titled Heech, which means “nothing.” One, a bronze on wood base (1972), looks like a calligraphic letter, but is an invention of the artist. In a rebellious spirit, many painters during this era of Pop art depicted severed hands, especially in the Saqqakhaneh section. The hands refer, as Iranians would know, to a beloved martyr whose arms were cut off before he was killed in battle in 680 A.D., a seminal event in Shiite history. In a 1962 untitled work, Mansour Ghandriz (b. 1936) used colored chalk and crayon on paper, and it’s clear that he absorbed the influences (color, line, and composition) of Paul Klee and Joan Miró. The effect is strange, but beautiful.

The Abstraction and Modernism room features Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian’s (b. 1924) mirror-glass three-dimensional sculptures and paintings under glass that produce optical illusions. She and some of the other artists parallel Pop Art both in timing and thematically. She studied and lived in New York City in the 1940s and ’50s and was part of its avant-garde arts scene. Among other projects, she collaborated with Andy Warhol on advertising illustrations; her Mirror Ball was loaned by the Warhol Museum.

The last room, Politics and Modern Iranian Artists, has some powerful images. Among the best are the photographs of Abbas Attar (b. 1944, a photographer who just goes by his first name) showing supporters of Ayatollah Khomeini and also one terrifying image of the lynching of a supporter of the shah. A 1975 aquatint by Nahid Hagigat called Escape shows a nude woman who has thrown off her chador.

This exhibit is certain to open your eyes to the modernity of Iran’s artists and also provoke many more questions. Iran Modern illustrates the many ways in which Iranian artists integrated Persian miniatures, Pre-Islam imagery, imagination, ingenuity, and Western ideas. While the show has tremendous variety, it also makes sense as a whole.