Column Name

Title

David Dubal is well known through his piano literature classes, his radio programs about the piano, and his books (some illustrated with his own drawings). An original and provocative thinker, he possesses one of the best senses of humor around. But few have been aware that his wit also expresses itself in visual art. This oversight will be corrected when Gallerie Icosahedron presents a large exhibition of Dubal’s drawings and paintings from December 5 through the end of the year. His only previous show was in Fort Worth in 1993, consisting of 100 line drawings exhibited at the Van Cliburn Competition. Except for the portraits of composers and musicians published in his books, his art is totally unknown.

Body

Although he has drawn and painted his entire life, Dubal, 67, counts himself fortunate enough not to have had to enter the commercial art world, since he was able to earn a living from music. For him, making art has been (as he explained in a recent interview) “neither about ego nor money,” but rather, a way of promoting his own happiness. And he is hopeful that exhibiting his art will now add to the pleasure of others.

In terms of formal training, the precocious young Dubal, who grew up in Cleveland, started going to the Cleveland Art Museum with his mother at age 5. He studied drawing and painting with Vincent Ferrara and Thompson Leonard, both Cleveland artists, from 13 to 18. He also copied “anything and everything.” Ohio State offered him a scholarship in visual arts, but he opted to continue in music instead. Dubal had yearned to play the piano from the age of 7, but only began lessons at 9. At that point, music took over as the driving force in his life.

Nonetheless, he has continued making art, averaging as many as 300 drawings and paintings in a year. He has said that he never uses models, but draws only from memory and imagination. He frequently “copied” (and continues to do so) drawings by old masters whom he worships, such as Degas, Michelangelo, Francois Clouet, Rembrandt, and others. He always does this in a free style, considering the process as necessary for his hands and eyes. In fact, they are somewhat like playing scales and arpeggios on the piano. From more recent art history, his inspirations are Miro, Matisse, and Klee.

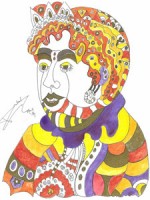

So by now you must be wondering what his art looks like. Dahlia Chako, director of Gallerie Icosahedron, describes Dubal’s drawings as “a lexicon of illustrations of the inhabitants of the village of perfect dreams. The vigilant guardians of this magical land sport such elaborate detail, they appear to have been surreptitiously photographed.”

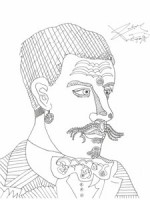

Dubal usually works in series, and dates his works. His drawings oscillate between simple, fluid lines and more decorative, textured works. There are varying motifs and styles. He loves stylized and fantastical musculature, feet, fingers, animals, and daffodils (“the first flower I was ever aware of,” he says). His subjects include men, cats, flowers, and fantasy landscapes. There are girls and lions, mothers and children. One story he tells is of seeing a photograph of Wanda Landowska, who dragged her harpsichord to Tolstoy’s estate. Dubal loved the photo of Tolstoy with Landowska so much that he later made a drawing of it from memory. When I suggest that his drawings bear similarities to Al Hirschfeld and Saul Steinberg, he seems unaware, and certainly uninfluenced by them.

The lines—fluid, sure, and unerring—of one drawing give it a Matissian quality. It depicts two nude women, one of them an angel. Her wings consist of Dubal’s multifaceted doodles. But wait, her right hand is a snake’s head with teeth! Another one pictures Saint Cecilia, patron saint of music, with her organ, surrounded by several cowled monks in curved contours. Other lines in the drawing suggest arches and crosses in a church. Is this a cathedral of art and music?

Yet another drawing shows Jesus on a cross, the face somewhat resembling a self-portrait. He is flanked by two smaller crosses, atop one of which is a head; above Jesus’s cross shines a halo. Under Dubal’s dated signature on the right, he has written, “Art thou in heaven!” (which I believe to be a pun that art is heaven).

I noticed that very often his women are surrounded by a lot of hair or an aura, like a kind of mandala. “Yes,” he said, “because women mean everything to me! They’re the superior creature of the world, way above all men. You notice, often my men are so horrible-looking! Look at this guy! Maybe I saw him on the subway. Now, when I do the women, they have a sense of idealization.”

I tell Dubal that I feel like I know these people; they are not “nobody.” When I suggest they might be conglomerates of people he’s seen, he agrees. And he adds that he can do likenesses “like some people have perfect pitch. This could be a man I saw somewhere. I am haunted by the human face.” In fact, he says he sometimes fears he is putting himself in jeopardy because he looks at people on the subway (despite the city’s unwritten rule of not staring at strangers), and is always drawing them.

Dubal admits that he had long mistakenly devalued non-objective art—but, strangely, about 1995, he started making it himself. He was surprised to find it was just as difficult to make as representational art. His colorful, mixed-media abstract paintings bear familial resemblances to Mark Tobey, Bradley Walker Tomlin, and other abstract expressionists, but are not influenced by them, since he doesn’t even know their work.

One series of abstract watercolors with ink and patches of glitter in various colors was produced mainly in 1999. They resemble fairs, carnivals, or perhaps, his own private universe. These are “a very different kind of genre,” he claims. Several are in the show.

Dubal has said that, as he gets older, art grows more and more important to him. He has an almost obsessive need to draw and paint.

A concert series at Gallerie Icosahedron has already featured numerous musicians, including many Juilliard students and alumni. There will be an exciting program of concerts in connection with David Dubal’s exhibition. Check the gallery’s Web site (icosahedron.com) for further information. Gallerie Icosahedron is located at 27 North Moore Street, right around the corner from the Franklin Street stop on the No. 1 subway line.