Column Name

Title

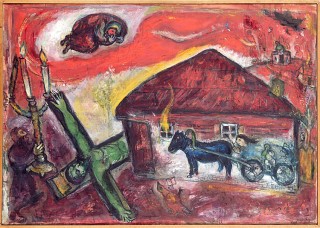

Obsession (1943), oil on canvas, 76 x 107.5 cm.; photo by Philippe Migeat

The Jewish Museum’s current show—Chagall: Love, War, and Exile—is a revelation as it provides new insight into a rarely seen side of this Jewish-Russian-French artist. (An additional reason to see the exhibit is that there’s a Juilliard connection: it’s sponsored by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation, which has given another big scholarship gift.)

The exhibit is up through February 2. The Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Ave., at 92nd St., (212) 423-2300

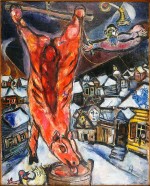

The Crucified (1944), pencil, gouache, and watercolor on paper, 25 1/2 x 19 5/8 in.

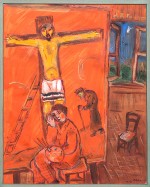

(Photo by Israel Museum Jerusalem/Avshalom Avital)The Artist With Yellow Christ (1938), gouache and pastel on paper, 22 3/8 x 18 1/4 in.

(Photo by Artists Rights Society )Body

We are accustomed to seeing the joyous Marc Chagall, with his lovers flying through the air to embrace each other, such as his Birthday (1915), in which Marc jumps impossibly upward, backward, and upside down to kiss his beloved Bella. In other early paintings, fiddlers play on rooftops. Chagall’s luminous murals at the Metropolitan Opera House depict the power of music. However, few are aware of his artistic responses to suffering—both personal and universal—especially during the rise of Nazism and the Second World War.

This exhibit allows us to experience Chagall in a new way. I was especially surprised by the small pen-and-ink drawings dating from 1931, including The Pogrom, The Prisoner, and The Burial. These were part of a series accompanying Abraham Lyesin’s poems about the horrors inflicted on the Jewish people in Russia before and during the Russian Revolution. In them, Chagall includes images of his mother and her grocery store, as he does in many of his paintings and drawings, but here he includes memories of happier times blended with sorrows in a manner that he did not do before.

Although the show has several parts and moods, among the most memorable images are the recurring depictions of Jesus’s torment on the cross. In some paintings, a Jewish Jesus, draped in a tallit (prayer shawl), symbolizes the anguish and repression of all people—especially the Jews. Surprisingly, Chagall is not the only Jewish artist to depict crucifixions. Indeed, the exhibition includes a catalogue from a 1942 show from the Puma Gallery in Manhattan called Modern Christs that included 17 Jewish artists among its 27 participants. The best known of these were Adolph Gottlieb, Louise Nevelson, and Max Weber. However, I know of no other Jewish artist who treated the theme as frequently as Chagall.

Chagall’s depictions of Jesus did not begin with the Holocaust. In fact, he drew a crucifixion as early as 1908, and made paintings of the Holy Family (1910) and the Madonna and Child (1911) as well as creating subjective renditions of both Golgotha and Calvary in 1912. Calvary is so personal that the artist’s mother and father stand at the foot of the cross. But it was during the 1930s and ’40s that Chagall became really obsessed with Christ on the cross. In the earlier works, his interest can be attributed to the Christianity that surrounded him as he grew up in Russia. During the ’30s, however, the crucified Jesus had clearly come to represent for him the suffering of the Jewish people. This subject has many ramifications, but perhaps the most important was to alert Christians to the atrocities that were being perpetrated on Jews by the unprecedented terrors of the Holocaust. Of the 31 paintings and 22 works on paper in the show, at least 18 deal with this subject.

In these crucifixions, Chagall transgresses in several ways—as a Jew, he appropriates Christian imagery, and he also goes against the currents of Modern art since, unlike many Modernist artists, he never abandoned imagery. Indeed, Chagall has been called many things, but he has never comfortably fit into any single category. Mostly, but not entirely self-taught, the artist uses imagery that comes close to Surrealism, but he never belonged to the Surrealist movement. His 1912 paintings show affinities with Orphism and variations on Cubism.

In fact, imagery was particularly strong in this little-known middle period of Chagall’s career, in which he portrayed the crucifixion over and over. It is always a Jewish Christ, more often than not either a self-portrait or one with Chagall’s name on top of the cross replacing the usual INRI (“Iesvs Nazarenvs Rex Iudaeorvm” or “Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews”). Interestingly, even the original inscription was ironic, since Christ was taunted for claiming to be King of the Jews, but Chagall adds the extra twist of using his own name, sometimes adding an image of an artist with a palette, who is clearly himself. In The Artist With Yellow Christ (1938), a fairly small gouache on paper, Chagall portrays himself sitting beside the crucifixion painting he has made, as if he were at the foot of the cross, palette in hand. The overall tonality is red, with a blue patch where a window opens out. An old Jew with a cane limps along one side of the canvas, balanced by the ladder on the other side. In his later work, Chagall identifies with Christ more directly, becoming the crucified Jesus—he continued painting Jesus and crucifixion scenes into the 1970s.

In another striking crucifixion image, Flayed Ox (1947), a red slaughtered cow hangs as if from a cross. This grotesque ox image is reminiscent of the work of another Jewish Russian painter who later lived in France, Chaim Soutine (1893-1943). In this painting, Chagall recalls visits to his grandfather, who performed slaughters for religious rituals. A Hassidic angel flies over the artist’s childhood village of Vitebsk and neighboring villages.

The suffering, war, and exile parts of the show are bookended by happier times in the artist’s life. In the beginning, there are flowers, lovers, and the usual folk and peasant motifs combined with Chagall’s knowledge gained in Paris of latest movements (such as Cubism and Orphism, a Cubism spinoff). The last part of the exhibition illustrates first a mournful period after his wife’s death in 1944, and then his joy in a newfound love in paintings that more closely resemble the joyous, colorful, fantasy-filled Chagall most of us know.

But this show’s real importance is that it exposes us to another side of this multifaceted, totally original artist. A small exhibit that speaks volumes, it is well worth seeing.