Column Name

Title

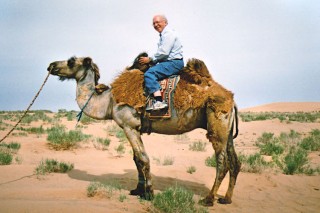

Joel Sachs in June 2005 in the South Gobi Desert.

The Republic of Mongolia was on the periphery of world politics from the death of Genghis Khan until the 1960-89 confrontation between the Soviet Union and China, when Mongolia was in every sense caught in the middle. Now it is back in the news as it exploits its enormous natural resources, which run from copper to fine horsehair for bows. My own experience there began in 2000, when my ensemble Continuum performed in the second Roaring Hooves Festival, which takes place primarily in the Gobi Desert and very small towns. Over the seven festivals in which I participated subsequently, I had many opportunities to see cultural life expanding despite the country’s many political and economic problems.

Body

In 2004, I was invited to join the international advisory board of the Arts Council of Mongolia (A.C.M.), an N.G.O. dedicated to fortifying and exporting Mongolian arts and bringing in foreign artists—essentially compensating for what the government has not been doing. The director, Ariunaa (Mongolians often go solely by their first name), is an amazingly gifted woman who abandoned her engineering career to help create and run the council, which has gradually grown and now has a large, competent staff of specialists. The international advisory board includes several Americans, most of whom have been deeply involved in funding or otherwise supporting Asian arts, as well as members from Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Korea, Serbia, and Sweden.

It has been fascinating to see the Arts Council’s scope grow and change, constantly modernizing and employing social media to spread the word. When I first came into contact with the council, its main project was the Red Ger, an art gallery that displays and sells works by Mongolian painters, some of whom are really impressive. (A “ger” is a traditional round, portable, Mongolian dwelling, which many people know by the Russian word yurt.) Since then, the A.C.M.’s scope has grown massively. One of its projects has been to get foreign tours for Mongolian performers, among them Arga Bileg, an ethno-jazz group that has played in New York. It comprises a pianist, who is also the group’s composer, two drummers, a yatga (Mongolian koto) player, and three morin khuur (“horse fiddle”) players, one of whom is an excellent throat singer. The group’s difficult-to-describe style might be called Franco-Mongolian. Other A.C.M. projects promote artist development, nomadic arts, and developing arts leadership, advocacy, and education. While it sounds like the A.C.M. is putting Mongolian arts into high gear, however, money is always an issue. One can only hope that the massive new mining industry will feel generous and help the arts to grow.

The occasion of my most recent visit was not a festival but an engagement to conduct the Mongolian State Philharmonic in Ulaanbaatar in March 2013. Over the years I had gotten to know Sansar Sangidorj, a remarkably gifted composer, pianist, and painter who divides his time between Mongolia and Virginia, where his wife, who’s also Mongolian, is a sushi chef. The concert would be a showcase for his music and a tribute to his late father, Choigiv Sangidorj, a much-loved composer who had died a year earlier. The main piece on the program would be the world premiere of Sansar’s new piano concerto. In addition to other pieces by Sansar, there would be pieces by his father, including 8:15, a short, dramatic commemoration of the bombing of Hiroshima.

The program also included Sansar’s best-known piece, Khara Khorum, for large ensemble with soloists on morin khuur and yatga, which he composed for Yo-Yo Ma’s (Pre-College ’71; ’72, cello) Silk Road Project. (Ma learned morin khuur for its premiere; the New Juilliard Ensemble premiered a version of it for viola and chamber orchestra in 2002.) Sansar’s concerns about the orchestra’s ability to learn new music turned out to be unfounded. The Philharmonic is quite good—a little below the level of some second-rank regional American orchestras and full of capable players and some really fine principals, some of them trained in the U.S.S.R. They quickly learned some unusual techniques and played very well. The bigger challenge was to break their habit of playing blandly. Despite an utterly chaotic dress rehearsal due to horrendous traffic, the concert was a resounding success. The 500-seat opera house was completely sold out and although the more modern-sounding pieces seemed to puzzle many listeners, the audience was incredibly enthusiastic.

Conducting the Mongolian State Philharmonic is on some levels similar to conducting any orchestra of a similar quality. This experience was unusual, however, because my previous trips have largely been to the desert and countryside, playing for isolated people who rarely experience live performances. Conducting in the capital brought home the division of the country into urban dwellers and “the rest.” Yet the nomadic heritage of the 50 percent of Mongolians living in Ulaanbaatar gives the underlying culture an unusual unity. Sansar’s own music is distinctive because he can draw upon the nomadic and the European worlds simultaneously or separately. It gives one hope that this large, economically divided country can achieve some unity through the arts.

I knew that Mongolia is full of surprises, but this visit concluded with one of the best—a postconcert farewell party that also celebrated the opening of an excellent Cuban restaurant owned by Sansar’s brother-in-law. Yes, a Cuban restaurant with a Cuban chef in Ulaanbaatar.