Title

Anyone who has watched the History Channel knows the standard American narrative of World War II in Europe: Normandy landings, Battle of the Bulge, liberation of Auschwitz, G.I.s kissing Parisians. The common view of the war in Eastern Europe, however, is quite different, and in most cases it lacks a jubilant moment of liberation since Nazi subjugation gave way to Soviet domination.

Body

Indeed, during the Cold War, the Soviet-aligned countries of what was then known as the Eastern Bloc all had official, state-sanctioned interpretations of the war that honored the Soviet Union as an unambiguous liberator. On October 28, I will present and discuss a piece of music from that era that implicitly challenged the standard view.

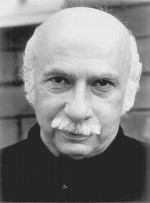

The piece is Giya Kancheli’s 1985 vocal-orchestral work Light Sorrow, which the Georgian composer wrote for the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and its music director Kurt Masur. At that time the Gewandhaus was the top orchestra of the German Democratic Republic (G.D.R.), or East Germany, the European country most closely aligned with Moscow.

The G.D.R.’s official view of World War II was staunchly pro-Soviet, calling the war a liberation from fascism because it brought socialism to German soil. On May 8, 1985, East Germany commemorated the 40th anniversary of that supposed liberation. Despite hushed-up memories of the Red Army’s brutality in the war’s aftermath—including mass rape—government-mandated celebration took place every year, and they were particularly strident in 1985: East Berlin resounded with military parades and Soviet war songs of the 1930s and ’40s while the top men of the G.D.R. and Soviet Union looked on.

Meanwhile, in Leipzig, Kurt Masur and the Gewandhaus premiered Light Sorrow, which Kancheli dedicated “to the innocent children who fell victim to the war.” It’s a meditation on the war’s meaning for Germany and Europe, and it rejects glorification of wartime heroism while emphasizing the war’s enormous human costs.

Like other pieces by Kancheli, Light Sorrow uses a dualistic musical language to represent good and evil; such a language cast doubt upon the official East German view of World War II. The good, depicted with children’s choir, plainchant-style singing, and pipe organ, evokes practices and beliefs that the party distrusted or rejected, especially Christian faith and—through the singing of texts by Goethe, Shakespeare, Pushkin, and the Georgian poet Tabidze—the existence of a universal and timeless human condition. Evil, by contrast, is instrumental and raucous, resembling the sonorous experience of an East German war commemoration. Heavy brass and percussion, especially snare drum rolls, move in tight unison, like the churning gears of an armed battalion, if not Marx’s concept of historical progress. Light Sorrow was a great success with its audience and, by and large, the Leipzig press. Critics interpreted it as a call to meditate on the costs of World War II and war in general. They did not mention the ways in which Kancheli’s commemoration departed from the state’s official view of the war. After all, he drew attention to topics that could only be openly addressed after the fall of the Communist regime. But the nature of the piece, as critics described it, so greatly diverged from the usual pomp and circumstance that an attentive reader could not miss the differences. And thus, though it was commissioned for the 40th anniversary of the so-called liberation from fascism, Light Sorrow also represented, in a more subtle way, a liberation from Communism.