Column Name

Title

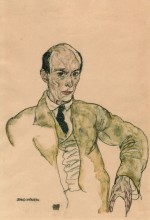

The exhibition Egon Schiele: Portraits, at the Neue Galerie through January 19, comprises about 125 drawings, paintings, and sculptures selected by the curator and world-renowned Schiele scholar Alessandra Comini. These works from museums and private collections in the U.S. and abroad give us an overview of this astonishing artist’s career. The exhibit shows how during Schiele’s short life (he died at the age of 28 from the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918), he evolved from a traditional artist to a startlingly original and controversial one and finally to a more acceptable Expressionist painter, alongside his colleagues, Gustav Klimt (who was also his mentor), Oskar Kokoschka, and Max Oppenheimer.

Body

Every one of the portraits in the show exudes immense power. Schiele succeeds in gripping the observer in a way few other artists do, capturing the essence of the anxiety-filled Austrian capital at the beginning of the 20th century. Indeed, the immediacy seems alarmingly relevant to our own troubled times.

In order to fully appreciate Schiele, one must place him in context; this artist emerged from fin-de-siècle Vienna, where Freud and many scientists, writers, artists, and composers, had begun to explore the inner workings of human emotions and instincts, instead of merely skimming the surface. Artists like Schiele, Kokoschka, Klimt, and Oppenheimer radically changed portraiture from literal representations of well-dressed upper-class people in luxurious surroundings to expressive images, characterized by wildly slashed-on brushstrokes; most of them accentuate eyes and hands. Often Schiele amputates limbs, and depicts his sitters with grotesque facial expressions; a kind of ugly rawness engulfs figures that have minimal or nonexistent backgrounds, or what Comini calls “angst-filled voids.” Schiele, in his numerous self-portraits, lops off his hands or feet or a finger. The act of cutting off his hands, the chief tool of an artist, seems especially self-punishing.

Although there is no prescribed order in which to view the exhibit, I would recommend starting in the room to your right as you enter. There we observe the early stages of the master’s art, when he was a student at the Vienna Academy and produced a number of copies from plaster casts (the common teaching practice at academic art institutions at the time) and studies from live models. Although these technically excellent drawings demonstrate great skill, Schiele soon rebelled against academicism, turning a corner where he began to strip bare outer layers of reality in order to plumb the depths of the human psyche. What he retained from his academic training, however, was an exquisite mastery of line, which was to serve him throughout his tragically short life. He used these lines in his numerous self-portraits to depict his angular and bony body, often in the nude. Sometimes he showed himself in the grips of obvious sexual passion or frustration. Still shocking today, these were even more scandalous at the time.

Schiele’s portraits of himself and others invariably place strong emphasis on faces and hands. A 1910 portrait of Eduard Kosmack is representative of many of these portrayals. In this painting, he focuses on Kosmack’s eyes and gnarled hands. The white aura surrounding the sitter may represent a shadow or a doppelgänger—a device Schiele used often. He leaves the rest of the background empty.

In some ways, Schiele’s viewpoint comes close to that of his composer friend Arnold Schoenberg, who painted seriously for several years, and who said of his own painting: “I never saw faces, but because I looked into people’s eyes, only their gazes… A painter, however, grasps, with one look, the whole person—I only his soul.”

Neue Galerie viewers benefit from Comini’s foresight; she traveled to Vienna as a graduate student in 1963, when Schiele’s sisters and some of his models were still alive. She interviewed them and found and photographed the prison cell where he was incarcerated in 1912, after an unjust and unproven accusation of “seduction.” One small room in the exhibit is dedicated to the 24 days the artist spent in jail, and this period represented a pivotal point in Schiele’s career. After that he frequently represented himself as a martyr. But that would change in 1914, when he met Edith Harms, a respectable bourgeois woman, whom he would marry the following year. During the last few years of his life, his painting became somewhat less controversial and, to my mind, less interesting.

Summing up the exhibition, Comini explains in the audio guide, “Schiele went from the age of Angst to empathy. His motto became ‘Many artists can look, but only real artists can see.’”

Do not miss the related exhibition on the second floor of the museum of the work of Schiele’s colleagues called Austrian Portraiture in the Early 20th Century. It helps to further contextualize the art of this unique individual.