Column Name

Title

Subhead

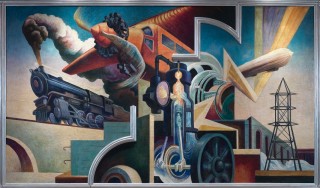

Thomas Hart Benton, “Instruments of Power” from America Today (1930–31), a mural cycle consisting of 10 panels, egg tempera with oil glazing over Permalba on a gesso ground on linen mounted to wood panels with a honeycomb interior

(Photo by Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)The exhilarating and enlightening exhibition currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called Thomas Hart Benton’s America Today Mural Rediscovered features a huge mural cycle the artist made for the New School for Social Research in 1930-31. It is displayed in a gallery that replicates its original 30-by-22-foot site at the New School—where I first saw it around 1980—and it consists of 10 panels that are nearly 8 feet high and were created to wrap around the walls of what was initially a board room in the original New School building, on West 12th Street. As is the case with so many murals, this one had been largely neglected; chairs carelessly pushed against it had begun to damage it quite extensively.

Body

At the time he painted the work, Benton, who used egg tempera, was said to have been so pleased with the commission that he refused payment, accepting only dozens of eggs in return. About 50 years after its installation, the New School put it up for sale and it was eventually acquired by the AXA Insurance Company, in 1982. After two years of cleaning and restoration, the company unveiled it in the lobby of its new headquarters, at 787 Seventh Avenue. The mural was later moved to a different lobby, just a block away, in 1996. But in 2012, due to yet another renovation and move, AXA decided to donate the work to the Met, where it will remain on permanent display.

The current exhibit provides not only the opportunity to see the mural in a re-creation of its intended setting, but also shows the viewer how Benton went about preparing to paint his vision of the America of 1931. Adjoining galleries show the artist’s numerous studies, sketches, and maquettes made during his travels throughout the United States. They also include some works that influenced him, as well as a number of paintings by artists who were strongly affected by him (the most famous of whom was Jackson Pollock).

In 1968, after viewing the mural for the first time in a decade, Benton told The New York Times that it “wasn’t supposed to be a work of social protest at all. Just a report on American life before the Depression. Except that it wasn’t clear that there was a Depression until I was almost finished with it. So I put in that bread line over the door.” The mural conveys the overriding belief in progress and energy of the jazz age—it’s a thrilling, action-packed depiction of pre-Depression U.S.A. But the largest panel, “Instruments of Power,” does contrast with the smallest, “Outreaching Hands,” which alludes to poverty and misery.

Benton, later known as a regionalist, included several regions of the U.S. in this ambitious mural: the South, the Midwest, the West, and New York City. Manual labor in the South and Midwest counterbalance the wheels of technology and industry elsewhere.

The scenes that make up the mural’s individual panels—huge, heroic, double-jointed, muscular bodies of workers in rural settings—contrast with rhythms of city dwellers in the subway, at a soda fountain, a boxing ring, at the movies, and at a burlesque show. Everything zigzags with breakneck speed, syncopated by silver painted Art Deco wood moldings designed by the architect Joseph Urban. Benton is always conscious of reflecting, echoing, or playing with forms that complement the moldings.

Unlike many artists (whose development usually progresses in the opposite direction), Benton became a Modernist/Abstractionist early on, around 1914-17, before settling into his later, recognizable, representational style. He had studied in Paris in about 1906 and 1907 and became close friends with the American Synchromist painter Stanton MacDonald-Wright, an artist who was greatly influenced by Orphists (a movement named by the poet Apollinaire in about 1912 because of its affinity to musical abstraction), Robert and Sonia Delaunay, and others. Benton adopted their use of colorful round shapes in motion, which served him well in his distinctive figurative works.

Ironically, the artist, who later came under attack by left-wing artists and critics as well as modernists, was both modernist and leftist in America Today. While he was sometimes criticized for vulgarity of subject matter, he was nonetheless hailed in Marxist magazines by contemporaries who appreciated his sources. José Clemente Orozco, the great Mexican muralist who worked on a different mural at the New School at the same time Benton was working on America Today, undoubtedly influenced Benton; both set a precedent for many Works Progress Administration murals that were to be commissioned later in the 1930s and early ’40s.

It’s easy to miss this modest exhibit in view of all the splashier, better-publicized shows currently at the Met. But don’t make that mistake: this groundbreaking, original exhibition is well worth seeing.