Title

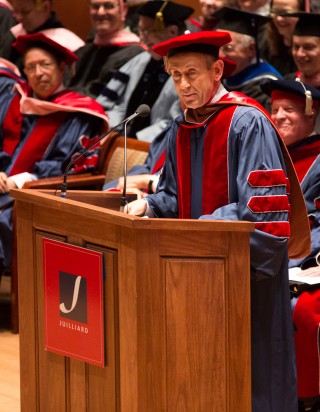

Nicholas Hytner addresses Juilliard's Class of 2015.

(Photo by Rosalie O'Connor)Juilliard celebrated its 110th commencement on May 22 with the conferring of 250 undergraduate and postgraduate degrees and five honorary degrees. British director Nicholas Hytner, one of the honorary degree recipients, gave the speech reprinted below, which you can listen to here. The live-stream of the ceremony was viewed in more than 20 countries.

Body

President Polisi, Chairman Kovner:

You honour me greatly by inviting me to speak in front of my fellow honourees, your world famous faculty, and the friends and families of this morning’s supremely accomplished graduates. But I can think of no greater honour than to salute those graduates as members of a small, dazzling club to which you and only you will ever belong: the Juilliard Class of 2015.

But still I ask myself, why have you asked a guy who’s spent the last 12 years leading someone else’s National Theatre to talk to you about your future? What do I know?

Well, I know, of course, about the rigour and seriousness of your training: my life has been immeasurably enriched by countless great artists who have trained at Juilliard. But I come from a world more often peopled by graduates of the great London schools of music, drama and dance, where the training is also quite superb, and whose graduates are also strikingly talented.

So why do I approach you with an awe and excitement that I’m not sure I’d feel in front of any other congregation of young artists? And I realise that from afar, for me the word Juilliard has always evoked not only excellence, not only dedication to the highest creative ideals, but also—in a word—glamour. So that’s why I’m here—to tell you how mythically glamorous you are; and I wondered in advance whether the reality would measure up to the myth. And I can tell you, now I’m finally in your company, that yes, you all of you shimmer with that aura that dances round people who know that they contain multitudes and it’s time to unleash them on the world outside.

And I’m not talking about that easy glamour you can buy from Prada, and parade on a red carpet, though I’ve got to say you’re all looking pretty good this morning. No: what I admire about you is the ferocious dedication you’ve brought to preparing yourself for this life-changing moment. I want to say that I admire your parents and your families too, because they’ve supported you, lived with your obsessions, loved you for your crazy enslavement to your art, and it would have been so much easier if you’d only said: “Mom, Dad, the thing I want most in the whole world is to go to Business School.”

And I’m sure lots of them said to you, when you said that this was the only life you could imagine for yourself, that it was a hard life, unpredictable, full of cruel disappointments. But here you are, connected through your training to your very core, ready to communicate everything that is communicable only through art.

And it won’t be easy. Most likely you won’t be rich, or powerful, and it will sometimes be disappointing. But I’ve been thinking about those old European opera houses, where—facing the magnificent gold proscenium arch of the stage—is the royal box. It’s often framed by a kind of small-scale, imitation proscenium arch, done up with gold cupids and red velvet swags, in desperate competition with the main event. The king used to sit there. Stalin sat in the one at the Bolshoi. Nowadays, powerful, grey men and women sit beside the enlightened patrons who have helped to pay for what’s happening on stage. They’re the smart ones who went to Business School.

Well, I’ve got to admit that I’ve sat there too, because sometimes the director of the theatre has to babysit the king. And here’s what I’ve discovered: when the play begins, or the musicians take up their instruments, or the singers sing or the dancers dance—even the occupants of the royal box defer to you, and want to share in your mystery.

And not just them. The house will be filled with those who deal in the routine dishonesties of the world. I hope you’ll challenge them with the truths you tell, as well as offering them intimations of beauty that are beyond their control. I hope you set the crowd in the gallery roaring at the absurdity of the lies they are told, and the lies they tell each other. I hope you entrance them with images of celestial harmony, and enrage them by holding the mirror up to the mess we make of ourselves and the mess that’s made of us. That’s what your great forbears did, and you’re much closer to them than you think.

I remember directing Oscar Wilde’s Importance of Being Earnest in London back in the '90s. The incomparable Maggie Smith was Lady Bracknell, and--to be honest – I was making heavy weather of it. So she took me to lunch at John Gielgud’s house, to talk about his famous productions of the play. Gielgud was one of the very greatest actors of the last century, possibly revered even more than his contemporary Laurence Olivier, and famous for seizing any opportunity for putting his foot in it. He played the title role first in 1930, and then again in 1939, when he also directed it and cast the redoubtable Dame Edith Evans as Lady Bracknell, and she walked away with the production. Maggie was convinced Gielgud would have the key to the play, but as we sat down to lunch, he was still furious with Dame Edith for stealing the show in 1939: he insisted that Lady Bracknell was a minor supporting role, and he couldn’t understand why Maggie was wasting her time with it.

Then he remembered being visited in his dressing room by the elderly Lord Alfred Douglas, who – in his youth - was Oscar Wilde’s abysmally narcissistic lover, and the cause of Wilde’s arrest and imprisonment for the crime of homosexuality. Gielgud asked Douglas about the opening night in 1895, but all Douglas claimed to remember was that he’d written most of the best lines himself. Gielgud might have had better with luck with another acquaintance, George Alexander, the actor-manager who had commissioned the play from Wilde and had been the first Jack Worthing, but he despised Alexander. “We all hated him,” said Gielgud, “because he behaved so disgracefully to poor Wilde when he came out of gaol.”

So I’m sitting at John Gielgud’s table, talking to him about these two men he’d known, one of whom had worked with, and the other gone to bed with, the playwright who wrote The Importance of Being Earnest. And now I’m telling you, which means that you’re only three degrees of separation from Oscar Wilde.

But meanwhile, Gielgud had moved on. He gave us some wonderfully precise advice about phrasing, about where to breathe if you wanted to do proper justice to Wilde’s perfectly poised dialogue. He talked about the differences between the 1930 production, which created a stage world at the furthest possible remove from naturalism; and the 1939 production, which he thought found a balance between an elaborately realistic environment and the actors’ acknowledgment of the artificiality of Wilde’s wit. He talked about the great Anglo-Irish comic tradition: comedy of manners it may be, but it was built on a bedrock of truth.

And then he asked Maggie how much she’d been paid for her latest movie.

You may already recognise yourselves in all this. Performing artists get together and first they gossip, then they dish the opposition, then they talk passionately about art, about technique, about truth; and then they bitch about money.

And you’ll be worrying away at the same insecurities, dreaming the same dreams and sharing the same ideals and ambitions as generations of artists before you. You’re a hair’s breadth away from the actors who played the first performance of The Importance of Being Earnest at the St James’s Theatre in 1895; from the dancers who braved the storm of booing at the premiere of The Rite of Spring in 1913 at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées; from the singers and musicians who gave Mozart a desperately needed success at the Theater auf der Wieden in 1791 with The Magic Flute. Hell, you’re only a step away from the first night of Hamlet.

And you have this in common with them, too. They knew the difference between success in the eyes of the world, and real success, which comes when you know you’ve done the best work you can in something that’s worth doing.

But you should seek out connections not just with the past, but in the here and now. Don’t immerse yourselves so completely in your own art that you can’t be reached by art that’s strange to you.

My fellow honouree Suzanne Farrell made ballets with George Balanchine. Balanchine commissioned scores from Igor Stravinsky. Stravinsky composed his opera The Rake’s Progress to a libretto by the great English poet W.H.Auden. Auden shared a house in Brooklyn for a time with Gypsy Rose Lee, who—in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1936—took over the role created by Josephine Baker. And by the way, the dances in that show were created by Balanchine.

How much better you’ll be if you’re hungry for all the art that’s out there, high and low! Balanchine made art for Ziegfeld, so maybe you can be true to yourself in more or less anything. Though the actors among you may want to reflect that you won’t find Meryl Streep in any of the Transformers movies.

But the best performing artists, in my experience, are endlessly curious about their fellow artists, and about worlds far from their own. You can surely hold two thoughts simultaneously in your head: first, that there is nothing better or truer than a Bach unaccompanied partita so there’s no better way of spending your time than with your violin; and second, that there are countless other ways of looking at the world, so it would be good to get out to an exhibition, a play, a movie, or a party where there’ll be people who know nothing about Bach but may have lots to say about Jay-Z. Plus, there’s always the possibility you may find someone at the party so lovely you don’t particularly care what they know about anything.

But I’ve never known a great performing artist who isn’t alert to what other artists can bring them. At the National Theatre’s 50th birthday gala, actors in the 2013 company shared the stage with actors who’d been in Laurence Olivier’s original 1963 company, and actors from every company since. And of course, in rehearsal, the kids never took their eyes off Maggie Smith, Judi Dench, Michael Gambon, Helen Mirren and Ralph Fiennes. But neither did the greats take their eyes off the beginners. “What do these kids know that I don’t know?” is what they were thinking. “What can they teach me?”

And, of course, there’s plenty you—the kids—can teach them; not least your determination to reach way beyond the royal box with your art, and to share your gifts with everyone you can touch through them.

There’s a British children’s party game called Pass the Parcel. You probably have a version of it here. You sit in a circle and pass round a big, many-layered parcel; and when the music stops, if you’re the one left holding it, you tear off a layer of wrapping. Then the music starts, and you pass it round again. You want to be the one to rip off the final layer, because then you get the prize. But the prize is never as good as you think it’s going to be—the joy is in ripping off the paper in expectation of the prize.

It’s the quest for the grail that counts. The grail itself is just a cup. You’ve already embarked on that quest, and I hope it lasts you a lifetime. Dream if you will of that moment when you rip off the final layer, you grasp the glittering prizes, and you’re finally pleased with yourself and the world is pleased with you. But if that ever happens, you’re no longer an artist. It is in that fevered search for the prize that you will find yourselves.

Listen, I don’t know how your lives will pan out, though it is my fervent prayer that each and every one of you will find the life that brings you the deepest possible fulfilment. You may be a dancer and director as vital to the history of her art form as Suzanne Farrell; or as miraculous a pianist as Murray Perahia; or as soul-stirring a singer as Dianne Reeves; or a director as mold-shattering as Peter Sellars. Or you may discover, like the inspiring women and men behind me, that it is your vocation to teach. Or you may, one day, decide to do something else entirely. But all of you, because of your talent and your dedication and your training here at Juilliard, have at your command something that most people yearn for all their lives, and achieve only rarely.

Through your art, you can lodge yourselves in the hearts of your fellow men and women. If only for a moment, you can penetrate to the core. You may lodge in thousands of hearts at a time, or in only one or two. It doesn’t matter. As you walk out from here, you know how to get through.

So let me finish with something I watched get through night after night. At the end of Alan Bennett’s play The History Boys, the ghost of the flawed but charismatic teacher, Hector, has these words to say to the class who loved him. I think he’s talking to you, too.

“Pass the parcel.

That’s sometimes all you can do.

Take it, feel it and pass it on.

Not for me, not for you, but for someone, somewhere, one day.

Pass it on.

That’s the game I wanted you to learn.

Pass it on.”