Column Name

Title

Everyone with the slightest interest in modern art knows how powerfully African art impacted Picasso, Braque, Brancusi, Modigliani, the German Expressionists, and countless others. Numerous exhibitions, some grand and some humble, have addressed this issue. What is less well known is how this art influenced New York artists, many of whom had studied in Paris—just a step removed from Picasso and Braque.

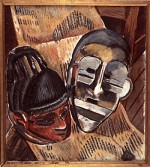

Mask (19th-early 20th century), We peoples, Ivory Coast; wood, hair, 9 7/16 in.

(Photo by Musée Dapper, Paris)Negro Masks (1932), Malvin Gray Johnson, United States; oil on canvas, 20 in. x 18 in.

(Photo by Hampton University Museum)Body

“African Art: New York and the Avant-Garde” is a modest, scholarly exhibition at the Met, but instead of rehashing well-worn stories, it reveals new and exciting information. Curator Yaelle Biro took a chapter from her doctoral dissertation, for the Sorbonne, and organized an exhibition around African art collected in New York between 1914 and 1923 and shows the influence it had on American and European art. Unlike many other exhibits of this sort, this one places the African art front and center rather than privileging modern art by placing it near generic African objects. Magnificent Fang reliquaries, masks from the Ivory Coast, and other objects elegantly hold their own, and some of the modernist paintings, sculptures, and photographs that were inspired by them are exhibited next to them.

The show is organized chronologically in four sections. At the entrance, there’s a 1909 photo of American artist Max Weber, who was returning from studying in Paris with one of the first African art objects to be seen in the U.S. In the photo he is holding the sculpture, a small Yaka Biteki fetish figure from what was then known as the Belgian Congo. Exhibited next to the photo is the sculpture itself.

The first of the four rooms, called 1914: America Discovers African Art, features a reconstruction of Alfred Stieglitz’s renowned Gallery 291. Exhibited in cases in front of a photographic backdrop are several of the art works that appear in the photo. Among them are a mask created by a We artist from what is now Ivory Coast, and a head from a Fang reliquary from Gabon, both shown in New York City for the first time since 1914.

The second gallery is called 1915-19: Acquiring a Taste for African Art. In New York City, the center of this new aesthetic, several dealers promoted African art, chief among them being the eccentric Mexican artist and gallerist Marius de Zayas (1880-1961). Photos by Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), who is better known as a painter, are shown with the African art they depict.

The third gallery, called 1919-23: A Move Toward Institutions, focuses on museums picking up on this trend, among them the Barnes Foundation, near Philadelphia, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney Studio Club (the forerunner of the present Whitney Museum of American Art). Outstanding in this gallery is a 19th-century Fang reliquary head from Gabon and a photograph by Sheeler of a 1923 Whitney installation called “Recent Paintings by Pablo Picasso and Negro Sculpture” in which the head appeared.

Most intriguing and innovative to me personally, the fourth gallery focuses on the impact of African art on the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement in the 1920s and early 1930s that included numerous art forms—visual, musical, literary, theater, and film. Philosopher Alain Locke (1885-1954), one of the foremost Harlem Renaissance eminences, worked with various benefactors and the magazine Theater Arts Monthly to acquire about a thousand African art works from diplomat and collector Raoul Blondiau. The collection, which Locke showed in New York in 1927, provided a source of inspiration for a number of African-American artists. A particularly interesting example is an oil painting by Malvin Gray Johnson (1896-1934) called Negro Masks(1932), together in an exhibition for the first time with the two masks he depicted, one from Nigeria and one from the Belgian Congo.

Years ago, in the course of writing my doctoral dissertation, I encountered a special case of the influence of African art on W.P.A. mural painters in Harlem Hospital during the 1930s. At that time, the artists painting murals in Harlem Hospital endured a scandal in which the superintendent of the hospital objected to depicting so many black people on the walls of the hospital. In the course of this racist attempt to discredit and destroy the art and artists, he enlisted several prominent black leaders who he hoped would condemn the work on the grounds that the African subject matter degraded blacks by making them think that they came from the jungle. The plan backfired when the leaders refused to cooperate and praised their African heritage—and the murals were completed as planned. After several restorations, the most recent one this fall, a number of these works are today prominently on exhibit in the hospital’s new Mural Pavilion (digital projections of the murals on the outside wall of the hospital are visible from Leonx Avenue).

Unfortunately we shall probably never know the names of the African artists who created these masterpieces that drove modernism—it is only quite recently that African artists have been accorded that kind of recognition. However, knowing exactly where in Africa the pieces come from and what their original functions were at least helps rectify some of the amorphous overgeneralizations of the past, when these works were merely labeled African, tribal, or, even worse, primitive.

This is exactly the kind of exhibition I, as an art historian, have been waiting for. It teaches a lesson without being overly didactic or condescending. It contains just enough information to make us want more; and at the same time it treats us to some of the most beautiful and inspirational art of the 20th century. In correcting some of the errors of the past, this exhibition sets a new standard for future ones. It’s just plain thrilling—don’t miss it!