Title

Hearing a posthumous premiere of a major work by a significant composer is at the very least a rare occurrence. However, Juilliard Orchestra audience members will experience exactly that as Dennis Russell Davies leads the highly anticipated North American premiere of Alfred Schnittke’s Symphony No. 9 in this month’s concert at Avery Fisher Hall.

Body

Schnittke (1934-98) was a remarkably prolific composer, and one of the most important figures in Russian music of the last generation. The last 13 years of his life found him in extremely poor health, although he continued to compose. As Maestro Davies explained in a recent interview: “He suffered several disabling strokes during the last period of his life. He wrote [the Ninth Symphony] at a time when he was not even able to use his right hand and arm. The manuscript of the piece was notated with his left hand.”

The symphony is Schnittke’s final work, and its composition occupied him from 1995 to 1997. It is important to note that this work is not like the posthumous symphonies of Beethoven, Schubert, or Mahler, for which autograph sources consist mainly of sketches and fragments. Rather, Schnittke bequeathed us a nearly complete work, entirely orchestrated, although one that posed many questions.

“[The manuscript] is extremely difficult to read,” observes Davies. “There is very little to indicate tempo, tempo changes, dynamics. Even the order of the three movements is not quite 100 percent established. But the notes are finished.”

The task of filling in the gaps was assigned to Schnittke’s friend and colleague Alexander Raskatov. The project of realizing the work was initiated by Schnittke’s publisher, which had been informed by the composer’s widow that a great deal of autograph material for a new symphony was extant. In turn, they approached the Dresden Philharmonic to discuss the possibility of officially commissioning the reconstruction of the work. A commissioning consortium—consisting of the Dresden Philharmonic, the Bruckner Orchester Linz (of which Davies is the music director and chief conductor), and the Juilliard School—was organized to provide funding for the project.

Davies is very pleased with the result. “Raskatov knew Schnittke personally. He knows his style very well, and I think he did a really remarkable job.”

The program also includes a new work by Raskatov, Nunc dimittis for mezzo-soprano, male voices, and orchestra. “At first, [Raskatov] thought he would write a fourth movement, and then he decided to go a different way and simply write a rather short but, I think, very moving memorial piece to Schnittke,” Davies explains. “The texts are liturgical texts and poetry by Joseph Brodsky, who was someone that Schnittke felt very close to.”

What sort of piece can the audience expect to hear? Davies says, “It’s in a very dissonant style, for want of a better word. Its use of the orchestra makes some extreme demands.” However, he adds, “It’s an outpouring from the heart. The testament of a still living but soon to be dead composer, with everything that that implies.”

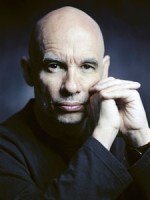

A Grammy Award winner and co-founder of the American Composers Orchestra, Davies—who is 63 and holds a bachelor’s degree in piano and master’s and doctoral degrees in orchestral conducting, all from Juilliard—is a seasoned interpreter of contemporary music. “I’m passionate about new music,” he says—a passion which, according to him, developed at Juilliard. “I was a pianist when I came to the School, and thought that was the direction my career would go. Then [I] got into orchestral conducting and was in Jean Morel’s class. There were some very interesting composers at Juilliard. I came out of the Midwest and didn’t really know much in the way of new music. Through the music of Ives and Copland, I became introduced to a native American language which appealed to me and which meant something to me. At the same time, Luciano Berio was on the faculty and, through the conducting program, I was asked to assist him on a couple of projects. It was for me a fascinating experience to be associated with composers like Berio, and through my work with the Juilliard Ensemble, with composers like Bruno Moderna and Pierre Boulez. They were all composers who were writing new music but were also very committed to performing older music. And to me, that was the way I wanted to go.”

His work with living composers has had a profound effect on his ability to interpret works of the standard repertoire. “I’ve discovered through working with composers how difficult it is for composers to notate what they really want. You’re dependent on the performer to breathe life into the piece. The fact that I could talk with Henze, Cage, Berio, and Copland … made it imperative that I have the same sort of dialogue with the older composers who could no longer talk to me. I had to learn to speak to them through their scores. Haydn, Beethoven, Brahms—they notated a great deal, but there’s a great deal they depended on us to already have known. That’s where I’m not really afraid to ask the questions and assume I know the answers.”

Although not a composer himself, Davies is remarkably sympathetic to many issues facing composers. Equally the advocate of the music of old masters like Haydn (whose complete symphonies he is recording with the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra) as of 20th- and 21st-century works (he conducted the premiere of Philip Glass’s new opera Appomattox at the San Francisco Opera last month), Davies is particularly opposed to the notion that every piece in a composer’s output represent a phase of stylistic progression. “It’s not that you’re speaking in a new language, it’s that you’re saying something meaningful in the language you can speak.” As we listen to a program containing pieces that seem to be stylistically at odds, we look forward to experiencing his claim that “more things make music [from different eras] similar than make them different from one another.”