Column Name

Title

The acts of diplomacy involved in obtaining loans from the Pakistani cities of Lahore and Karachi for the Asia Society’s fascinating and very beautiful exhibition, “The Buddhist Heritage: The Art of Gandhara,” were nothing short of spectacular. The show ended up opening in August, six months behind schedule. However, considering the increasingly escalating political tensions between the United States and Pakistan, the delay in launching the exhibition was minimal; indeed, we are fortunate that it is taking place at all.

Body

The Gandhara region includes northwestern Pakistan and a bit of Afghanistan, and it has been ruled by Persia, Greece, and India at various times over the past few thousand years. In addition to loans from Pakistan, the Asia Society has borrowed comparative materials from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a number of private collections, supplementing them with works from its own collection. The dates of the pieces range from the first century B.C. through the fifth century A.D. Along with the sheer quality of many of the Pakistani loans, it is the use of these comparative works from Greco-Roman cultures that makes the show so enlightening.

An immense stone statue in the first room, the Goddess Hariti With Three Children, epitomizes the synthesis of East and West that is apparent throughout the show. It dates from the second to third century, and is made from schist, a local rock used for many of the art works in the show. In it Hariti’s rippling, many-pleated dress, ample bosom, and intricate hairstyle and tiara look Roman or Hellenistic, but her gentle and peaceful expression combined with the appearance of one small child clinging to her breast and two more climbing on her shoulders are Buddhist in feeling. In all, the statue conveys a sense of playfulness mixed with seriousness, grace, and monumentality. I have never seen anything quite like it

As the exhibit demonstrates, the primary importance of the art of Gandhara lies in this unusual synthesis of East and West. Historically when a number of cultures have come together, the quality of the resulting art produced has far surpassed its disparate strands. (Think, for example, of Venice during the Renaissance, with its merging of European and Byzantine cultures). This is very much the case with Gandharan art, which combines the best of Greco-Roman antiquity with Indian imagery and local practices. The variety of sculpture, large and small, simple and intricate, meditative and baroque, reflects the region’s location on the silk road, where traders from many parts of the world congregated, bringing with them not only goods, but also religion, philosophy, and art.

A smallish stone first-to-second century River God from the Karachi Museum looks ahead to Michelangelo’s large Medici Tomb personifications of Day, Night, Twilight, and Dawn, which were inspired by Greco-Roman river gods. Another very small piece, a copper incense burner, possesses great power for its size, with its elegant leogryph (part lion, part griffon) handle. It seems that Gandharans burned incense in honor of the gods, as the ancient Greeks did before them. The exhibit’s additional classical influences are apparent in Dionysian scenes, depictions of Castor and Pollux, of Apollo and Daphne, satyrs, Atlas, and other mythological figures, as well as gods and goddesses. The curator’s illuminating placement of classical works beside the Gandharan ones enables observers to clearly see the numerous connections.

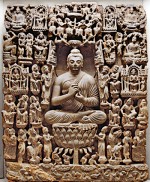

The second part of the exhibit focuses on Buddhas and Bodhisattvas; the pièce de résistance here is the fourth-century Vision of a Buddha’s Paradise. In this relatively large (46.9 inch by 38.2 inch) stone relief, the Buddha sits cross-legged in the center, on his iconic lotus blossom. He is being crowned by two tiny angels, and he is surrounded by smaller Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. The symmetry, the centrality, and even the act of crowning by angels looks to my eye to be very much of a parallel with the multitudinous tympana and altarpieces of Christendom. This vigorous, deeply carved relief is filled with figures in various kinds of physical motion, and the contrast between surrounding activities and the meditative calm and simplicity of the central Buddha, conveys a sense of a complex universe. This section of the show also includes standing Buddhas, classical Buddhas, heads of Buddhas, and some fascinating giant Buddha footprints that were used at times when depictions of the rest of him were not sanctioned.

A third section of the show attempts to place pieces in the context of their architectural narrative. Here we see various stories of the Buddha’s life, from his conception (curiously again, close to the immaculate conception of Jesus) to his rejecting riches, and what was to me one of the most moving of the panels, in which he parts from his horse Kanthaka, and the horse kneels in reverence and sorrow. Another panel, Mara’s Demon Army, features astounding caricatures of humans and beasts. Musicians might especially appreciate a scene in which the harpist Pancashika and Indra visit Buddha, who is meditating in a cave.

In all, the exhibition contains 75 sculptures, friezes, and other items, and they are characterized above all by warmth and humanity. Sometimes Buddhist art can be so intricate that it is impossible to appreciate without knowledge of its symbolism, but these pieces are very accessible to all audiences, whether or not one is familiar with the many manifestations of Buddhism.

Not mentioned in the show, though they undoubtedly linger in the memory of some viewers, are two gigantic sixth-century Gandharan Buddhas that loomed large in the international news in 2001. In March of that year, Afghanistan’s Taliban government deliberately destroyed these figures that had been carved into the rock at Bamiyan on the pretense that they were idols. World opinion strongly condemned this destruction, which was viewed as an example of the intolerance of the Taliban.

This long-awaited show is the first exhibition of this art in the U.S. in 50 years, but it is not likely to be repeated here anytime soon. And since it is highly improbable that most U.S. citizens will get an opportunity to go to this area in the near future, the Asia Society show provides a very special chance to see this fabulous art.