Title

Subhead

As New York prepares to honor one of its greatest cultural heroes, Leonard Bernstein, another New Yorker is getting ready to step into some big shoes. In 2009, Alan Gilbert will become the first Manhattan native to serve as music director of the New York Philharmonic. Mr. Gilbert recently sat down in conversation with Juilliard Journal writer Evan Fein to discuss his thoughts about Bernstein, the challenges of assuming the master’s old position, and Gilbert’s own role in the upcoming citywide celebration of the late composer-conductor’s 90th birthday—which includes conducting the Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall on November 14, the exact date of the 65th anniversary of Bernstein’s legendary debut there, and leading the Juilliard Orchestra 10 days later in a performance of Bernstein’s Kaddish and Beethoven’s “Eroica” symphonies at Avery Fisher Hall. Jennifer Zetlan will be the soprano soloist for the Kaddish, which will also feature Polish-born American international attorney and author Samuel Pisar as speaker. (Pisar wrote a new narration for the work, at Bernstein’s request, based on his own experience as a Holocaust survivor.) This concert will mark Mr. Gilbert’s first appearance with the Juilliard Orchestra since his days here as a student.

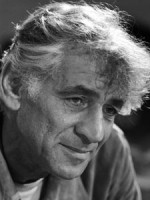

Leonard Bernstein in 1971. As part of a citywide festival celebrating the late maestro's 90th birthday, Alan Gilbert will conduct the Juilliard Orchestra in Bernstein's Kaddish Symphony on November 24.

(Photo by Marion S. Trikosko)Body

Why did you choose to pair the “Eroica” with the Kaddish?

It would be nice to be able to say that there’s always a philosophical connection—which actually, there happens to be between these two pieces. While Bernstein’s Kaddish is ultimately an optimistic work, it’s a prayer for the dead, and Beethoven Three has a funeral march—it’s about man’s quest for finding meaning and his place in the world. But actually, that’s not really why the program was decided on. We wanted, as part of this Bernstein festival that the New York Philharmonic is jointly presenting with Carnegie Hall, to do all of the Bernstein symphonies, and the Kaddish seemed like a very exciting piece to do with Juilliard students. Musically, educationally, it seemed like a wonderful project. The Beethoven Third is such a masterpiece; I think it happens to work well psychologically and philosophically with the Bernstein.

Have you ever conducted the Kaddish before?

No, I never have. It’s a piece I’ve only heard a couple of times. It’s exciting for me to do a new piece, and I’ve been studying away at it.

It’s sometimes considered one of Bernstein’s most difficult pieces, both for audiences and for performers.

It’s definitely a hard piece for the performers. I think there was something very sincere about Bernstein’s search. A lot of his music you can feel is about the quest for understanding, the quest for meaning: why we’re here, why there’s pain, why life is difficult, and ultimately, how to find happiness. It’s a prayer for the dead—obviously a difficult subject. In that sense, I think it’s a little bit of a heavy morsel to chew on. But on the other hand, Leonard Bernstein himself—and I think this comes though in all of his pieces—was such an optimistic person, and there’s something very honest and true about the struggle that comes out of his music. I think it’s something that people can really identify with, and it’s wonderful music.

Do you think Bernstein achieved resolution with these issues, in this work or in his others?

I think he never achieved resolution. … So many of his pieces end with a question mark. And somehow, that really rings true to me, because I think that it’s just when you think you have the answers that you realize that it’s more complicated than that.

Did you have the opportunity to see Bernstein conduct when you were young?

Oh, yeah! Many, many times! Basically every time he conducted here, I went to hear him. My parents were both violinists in the orchestra. My mother is still playing [in the orchestra]; my father retired six or seven years ago. But it was exciting for them, and my sister and I loved going to the Phil whenever we could, and certainly when there were exciting and important weeks, which was every one that Lenny conducted. I speak to young musicians today, and for them, Bernstein is a myth. They only see him in videos and hear him on his records, but for me, it was something I experienced live. I consider myself very lucky.

What is going through your mind as you prepare to inherit his orchestra?

It’s daunting, and if I look back to all the music directors who have preceded me, it can become fairly incapacitating, actually, because it’s such an amazing list. I have to approach it as who I am—I can’t try to be somebody else. I think that is the reason I was brought in: to be myself. I try to be mindful of the illustrious tradition that I’m following, but on the other hand, not let it completely take over. That would be too terrifying.

Is there room for another Bernstein in today’s world?

There will never be another Bernstein, because Bernstein was Bernstein. But there is absolutely a place for public figures who really stand for something and who are natural communicators, and who naturally rally a kind of a sense of civic and cultural pride in a community. And that’s something I think the Phil should try to do: to really stand for something that the city can rally around and be proud of. There should never be a whiff of exclusivity or of elitism in what an orchestra does. Music is for people, and it’s not just for certain people; it’s for all people, and Lenny was absolutely someone who believed this deeply and wanted to communicate with literally as many people as possible through his music. That’s something that we’re striving for here. I hear people [say]: “Well, people are not interested in classical music now. It’s only for a select few.” That’s complete nonsense. It’s a question of education, it’s a question of accessibility, it’s a question of speaking a language that people understand. The vernacular of our society is changing all the time, so we really have to be up to date.

Bernstein is known as one of the great music educators. Are you interested in working in the field of music education?

Absolutely. I’m definitely interested to conduct education concerts at the Phil. It’s something that music directors recently have often avoided. But I’m absolutely planning to do programs myself. Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts were definitive, and a lot of orchestras and conductors have tried to re-create the magic and rapport that he had with kids and with audiences. It may be impossible to do that in this day and age, [but] I think our best efforts are what are called for.

Do you foresee any direct collaboration with The Juilliard School?

Absolutely. I would like the connection between the two institutions to be powerful and real. To me it’s obvious, and not only because we’re neighbors, but because I think both organizations have so much to give each other. I’ve had long and fascinating conversations with [President Joseph] Polisi and [Dean and Provost] Ara Guzelimian. We’re working on exactly what form that will take, and when we can talk about it publicly. I’m happy to say that we are talking and looking for ways to make it a reality.

What lessons can we take from the example of Leonard Bernstein?

I hope I’ve learned a lot from Bernstein and from being around him. He was such an honest musician. He really felt when he felt extremely deeply, and went for it with everything he had, and I think that’s something that all musicians should do—first of all, to have convictions, but also to have the courage to realize them. He did that as well as anyone I ever saw, and that is something that I try to emulate. I think it can be a lesson for us all.