Title

Theater folk may have come to take it for granted, but if you really take a look, no other achievement in American letters matches it or likely ever will: Starting in the 1970s and ending shortly before his death of liver cancer in 2005, the man born August Kittel in Pittsburgh’s Hill District in 1945 wrote one play about black life in the United States for every decade of the 20th century. The scale of the task is telling, reminding us that American history is African-American history; not one hour of it is not affected somehow by the struggles and the suffering chronicled by August Wilson. (After his white father’s death in 1965, the playwright-to-be, then a poet, took his mother’s maiden name.)

Body

This month, Juilliard’s fourth-year drama students (joined by several third-year students to round out the cast) will present what is arguably the greatest achievement of Wilson’s 10-play cycle: Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, a wrenching drama of separation, loss, and reconciliation set in a Hill District boarding house in 1911. The director will be Israel Hicks, chairman and artistic director of the Rutgers University theater program. Over the past 20-plus years, Hicks has staged all of Wilson’s plays but the last, Radio Golf, most of them at the celebrated Denver Theater Center.

Wilson did not write his cycle in chronological order. Joe Turner came fourth, after Jitney, set and written in the 1970s; Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, set in the 1920s and first presented on Broadway in the fall of 1984; and Fences, the tale of generational conflict set in the late 1950s, which collected the 1987 Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award, and became Wilson’s longest-running work. One year and one day after Fences opened on 46th Street, Joe Turner opened a block away. Alas, the two plays closed the same day: June 26, 1988, giving the more spiritually disturbing Joe Turner a Broadway run of only three months. It received many nominations, but it won nothing.

The play’s critical reception, however, foretold the success it would have in revival from Henry Street to Harlem to (no doubt) Juilliard. Time magazine called it Wilson’s best play. Frank Rich, in The New York Times, said Joe Turner was “as rich in religious feeling as in historical detail … at once a teeming canvas of black America and a spiritual allegory with a Melville whammy.” Joe Turner’s Come and Gone is a thrilling, touching, heartbreaking, at times humorous family drama about the agonies of dislocation and of physical and spiritual loss. The title character, never seen, is the Tennessee bounty hunter immortalized in W. C. Handy’s “Joe Turner’s Blues.” The play revolves around one Herald Loomis, who, after having spent seven years on Joe Turner’s chain gang, appears at that Pittsburgh boardinghouse with his young daughter in tow, searching for his wife. The boardinghouse is also home to Bynum, a practitioner of roots and spells who once met and was profoundly affected by a “shiny man,” and has long hoped to meet him again. Both men’s searches converge in the play’s violent, surprising ending.

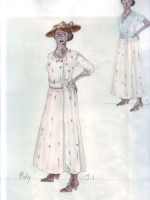

It might be more conventional to speak of Bynum’s shiny man as a “vision,” but if instead we take Bynum at his word, that he just plain met the shiny man, we open the door to the full power of Wilson’s art. Shiny men walk the earth in Joe Turner, while at the same time the play is obsessively naturalistic: the acting edition includes an 11-page costume plot and lists more than 200 props and set pieces, including meals served and eaten onstage. These endless concrete realities point to other, equally endless and concrete realities with which the characters live: injustice, separation, and loss of self and others.

Like all Wilson plays, Joe Turner packs in lots of language. The characters are compelled to voice their terrible histories, laboring over huge monuments of language amid the breakfast dishes. Wilson presents a daunting double challenge to student actors: they must play characters older than themselves, carrying almost unbearable burdens; and they must get through Wilson’s words while staying true to the playwright’s celebrated rhythms and music. Interviewed the day after his first meeting with the Joe Turner cast, Hicks spoke of these challenges.

“They will have to draw parallels with their own lives,” Hicks said, “and they will have to connect with the playwright’s images. They will have to find emotional connections between those kinds of experiences and who they are. I will be spending time finding out who they are by absorbing them in the work and asking them questions. I must pay attention to what each one of them brings me.” Hicks had also told his cast up front that, as far as the language was concerned, they would have to “move it”—without, of course, losing the remarkable resonances of Wilson’s storytelling.

“It won’t be hard with time,” says Sheldon Woodley of Group 38, who plays Herald Loomis, “because the music is pretty much in me.” That inner music, he says, has been cultivated by listening to favorite jazz legends like Roy Hargrove, Wynton Marsalis, and Miles Davis. “The tempo of the speech really relates to how Wilson talks about jazz,” he explains. “All of his writing has a certain rhythm to it. The characters go off on riffs the way someone in jazz has a solo.” The greater challenge for Woodley will be “to identify with that time period. We’re in a technological world right now, and to understand what it’s like to walk in a man’s shoes who traveled to Pittsburgh from Tennessee on foot, and what he went through on a daily basis during Jim Crow … I am an actor and can use my imagination, but to really understand what someone went through in that time is one of the difficult challenges for me now.”

Still, time is on everyone’s side—a luxurious six weeks, compared to the four Hicks has these days in most regional theaters. By the time you read this, the Joe Turner cast will be drawing their parallels and connecting to some of the most startling images in American theater history (or American history, period). “It's a big deal to be doing August Wilson in the main Drama Theater,” Woodley says. “In the outside black community there’s a misconception about the diversity of the program, and I think they’ll be pleased to see the work we're doing here at the School.”