Title

I was born in 1939 in upstate New York, a gay, athletic changeling in a repressed academic family that could not cope with unexpected problems or communicate truthfully. Among the many forbidden subjects that my parents—along with nearly everyone else at that time—particularly avoided was homosexuality. That condition was truly one that “dared not speak its name.”

Body

When I was 11, we were going on a vacation to New York City, and before leaving, my mother gave me my one and only educational talk about sex: In the big city I had to be on constant watch for homosexuals! She described these monsters following the stereotypes of the day, and I listened, transfixed with horror, understanding for the first time the attraction I felt toward Jerry, the blond, blue-eyed farm boy in my sixth-grade class.

Alone with my awful secret, I looked vainly for information. The definitive role model in the 1950s was, alas, Liberace. In the novels that I surreptitiously read (The City and the Pillar, The Counterfeiters), people led fabulously unhappy lives and everyone came to operatically dreadful ends. I felt no connection with these books, or with Tennessee Williams’ plays, or films like Tea and Sympathy, although they did tell me that there was another world out there. If I could just find it, as odd as it seemed, I would not be alone. Unconsciously, I was learning a larger lesson. In high school, I produced a weekly radio talent show that connected me with a large cross-section of my school classmates. I was presenting Negro performers (to use the common term of the 1950s) who were better musicians than I, both in popular and classical music. The Jewish and Catholic kids did not conform to the anti-Semitic and anti-Papist stereotypes of my upstate childhood. Realizing that I didn’t fit the straight image of the mincing pansy, I began to look at white denigration of Negroes, Protestant hatred of Papists, and the all-pervasive disdain of Jews. Something was wrong with all this racial, religious, and sexual loathing.

I was starting a journey that compelled me to simultaneously look outside at social bias and within at my own prejudices and fears. Finally, my alcoholic mother precipitated a crisis when she chose to “realize” that I was “one of those people.” Armed with passages from scripture, she tried to have me institutionalized. I resisted, and mother, battling her own inner demons, overdosed on sleeping pills and died. In the conflicted years that followed, I had to understand and release her, and, even more difficult, understand and accept myself—a long, and continuing journey.

One of my last self-protective walls crumbled when, in June 1969, a group of brave, flamboyant drag queens liberated the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, igniting the gay-rights movement. They were simply too fearless and strong to ignore, and their actions forced me to confront my fear of effeminate men as well any lingering self-hatred of my “condition.”

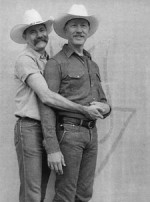

Liberation and spiritual growth live paradoxically where we feel weakest and most ashamed. In accepting our “faults” and in the honest naming of them, we lay a foundation of strength. I am blessed by the changes in society since Stonewall. Now, my loving partner Howard Kessler and I can live together openly, with our domestic partnership from New York City, our civil union from Vermont, and our marriage from Canada. We trust that full marriage will come to us in the United States, as civil rights have come to black Americans, and the vote and equal employment rights to women. We hope that the world we grew up in—in which jobs, families, homes, and lives—were lost over the mere suspicion of homosexuality, is receding into incredulous myth.