Column Name

Title

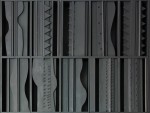

Louise Nevelson (1899-1988) is widely regarded as one of the greatest sculptors of the 20th century, and Juilliard is fortunate to have her dramatic Nightsphere-Light, which dominates the west wall of the Peter Jay Sharp Theater lobby. Measuring nearly 48 feet in length and 8 feet in height, it consists of two rows of 24 boxes containing a variety undulating, jagged, and geometric forms. It’s constructed of painted black wood and also surrounded by black, and in part because of the enveloping blackness, which was integral to Nevelson’s artistic philosophy, few people are even aware of its presence. Nightsphere is also easy to miss because it’s not especially well lit, and there is no identifying plaque. (It was removed during the recent renovations and is currently being replaced.)

Body

Although the piece seems to have been made for the space, Nevelson did not create it with Juilliard in mind. In fact, it was exhibited at the Pace Gallery before it was moved to Juilliard, in December 1969. Nonetheless when it was installed here, then-President Peter Mennin said in the Juilliard News Bulletin, “It fits in very well with the school’s architecture. And it seems musical, in that its rhythmical forms express variations on a major theme.” (The artwork had been purchased for the new Juilliard School by Lincoln Center with funds donated by collectors Jean and Howard Lipman, who also funded the acquisition of Lincoln Center’s important David Smith and Alexander Calder sculptures.)

Nightsphere was also illustrated in a 1969-70 Lincoln Center Playbill, in an article calling it an environment reflecting Nevelson’s philosophy. While Nevelson herself denied that it had anything overtly to do with music, you cannot always believe what an artist says about her work. Her series of 1964 sculptures “Self-Portrait: Silent Music” have a lot in common with Nightsphere. At least one of the sculptures in the series consists of 24 boxes painted black, which is very reminiscent of Nightsphere. And another Nevelson work made up of black boxes, presently in the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, has the musical title Black Chord. Between 1964 and 1969, Nevelson made numerous other works with musical referents, and her assistant, Diana MacKown, saw traces of violins and cellos in its abstract forms. MacKown also recalled that both she and the artist had had dreams about Nightsphere-Light.

One sunlit autumn afternoon, I took the students in my Art in N.Y.C. class to see Nightsphere-Light, and we happened to be there when the work’s blackness was suffused with rainbow hues from the reflections off the glass exterior of the lobby. The students (Kyle Athayde, Bo Hu, Bryan Carter, Corey Gerstenfeld, Thomas Mesa, Jordan Pettay, David Stevens, and Lila Yang) made the following observations.

They noticed the sculpture’s gigantic size, and the freedom the artist allowed for the viewer to construct his or her own interpretation. Its emptiness and blackness encouraged them to imagine a readable, though abstract, alphabet, with the random forms complementing each other. Many noted the contrast between man-made and natural elements. Some called it quiet and simple, remarking on the deceptively symmetrical shapes mounted in a minimalistic way.

Just as former President Mennin had, some students observed musical elements in the work, such as rounded contours that reminded them of string instruments or structures that brought to mind piano keys. They experienced tension and release that they interpreted as being parallel to shapes and contours in musical phrases. They felt that the titleNightsphere-Light captured both nighttime concert energy and the enlightenment that music provides. One student was reminded of Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time, in which the composer highlights certain instruments to color specific movements, but in which the totality of all the instruments playing together creates a unified texture. Comparing some of the artwork’s sculptural elements to the violin in the stratosphere in the last movement of the quartet, this student noted the beauty that comes with the absence of sound.

I noticed a lot of counterpoint in the artwork: round against straight, curves against points, solid against concave, drilled holes against three-dimensional protrusions. These observations led me to question whether any of the patterns repeat. Although they don’t, they do relate to each other in quirky and unpredictable ways.

I also observed how the top row of 24 boxes relates to the bottom one. Sometimes Nevelson used machine-made, found objects; in other works she cut holes by hand to achieve a raggedy, handmade effect. When you stand back fromNightsphere, you see the overall totemic look of the “figures.” That relates to the primitive and archaic goals of the Abstract Expressionist group to which Nevelson belonged. Strong and independent, she was one of very few women who was accepted into that masculine-dominated circle.

The separate boxes have been likened to miniature stage sets in which Nevelson sets abstract choreography, which is just one of the piece’s connections with the world of dance. Nevelson studied dance and refers to it in her writings, and in her use of black to both cover and unify the individual units, she has created a Martha Graham-like aura. This aura is also analogous to the black garb of musicians in an orchestra, where black has the effect of both sacrificing individuality and merging disparate parts into one. Perhaps it is the successful unification and subtlety of parts working together inNightsphere that most resembles the musical, dance, and theatrical collaborative processes.

Critics in 1969 took note of the same things that Mennin, my students, and I did, with one writer comparing the work to Bach’s organ music. John Gruen, John Canaday, and James Mellow, all major New York reviewers, noted musical, magical transformations in the piece, and could not find enough words of praise for it.

Juilliard’s Nevelson is one of a number of important public works by the sculptor in New York City. Another is the Chapel of the Good Shepherd at St. Peter’s Church at 54th Street and Lexington Avenue (1975-77), an all-white, five-sided space planned specifically for prayer and meditation. Night Presence IV, a 20-foot high sculpture, can be seen on Park Avenue at 92nd Street. Louise Nevelson Plaza, on Maiden Lane in Lower Manhattan, contains seven works, which like the one at Juilliard, are all painted black, but made of steel. The plaza has recently been restored by the city.

As for Nightsphere-Light, Nevelson may have intended to keep the sculpture a secret, revealing itself only to those who take the time and make the effort to seek it out. If that’s the case, she succeeded —if you have never noticed this important installation at Juilliard, you are by no means alone. But next time you enter or pass the lobby of the theater, take some time to look at it. It is always beautiful and mysterious, but it was particularly stunning that fall day, with the rainbow bringing to mind Nevelson’s often-repeated point that black is the sum of all colors.