Column Name

Title

Charles Burchfield (1893-1967) never literally composed music, but nevertheless the exhibition of his paintings and drawings, “Heat Waves in a Swamp,” at the Whitney, exudes musicality. This rings especially true in his earlier and later works. During a short period mid-career, he succumbed to the pressure to make money—either by producing decorative art (wallpaper, for example) or conforming to “American Scene” painting, which sold better than his mystical, ecstatic, and intensely private visions. This more conventional genre of painting also allowed him to experience a sense of belonging to the American artistic community, since it made his often mysterious art more “accessible.” Perhaps because the curator of the show, Robert Gober, is an artist himself, he has been extraordinarily sensitive and mindful of these issues.

Body

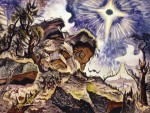

The staggeringly beautiful exhibit is puzzling, however, in that rarely does the word “synesthesia” appear in the wall labels, catalog, or press releases. Synesthesia, the joining of the senses that occurs when a stimulus in one modality evokes a simultaneous reaction in another (for example, color and sound), is apparent in all of Burchfield’s art. Nearly every work in this exhibit screams synesthesia. Like the composer Olivier Messiaen, a known synesthete, Burchfield compulsively catalogued nature around him early on. He was obsessed with sound and its visual representation. Hesaw the sounds of insects, of crickets, of cicadas, of lightning, and of church bells ringing in the rain. Or industrial sounds, as those of railroad trains and electrical circuits. And his art enables us to see and hear sounds. All of these and more Burchfield strove to evoke in his watercolors.

Interestingly, he rarely employed oils, preferring the fluidity of watercolor. Often commenting in his journals on watercolor’s superiority, he expressed dissatisfaction with his few, halting attempts in oil. The main difficulty of capturing synesthetic photisms (or visions) in paint, according to Carol Steen, a contemporary synesthetic artist, is the fact that they are in constant motion. Steen has recently used video, but Burchfield, lacking that avenue, sought to portray the movement of the sounds he observed via the rapidity of watercolor. Indeed, Burchfield himself used a musical analogy, saying, “The relationship between my watercolor and the traditional manner is the same as between Beethoven and the Classicists.”

Burchfield confined his early watercolors mostly to small formats, but later, in order to create large paintings, he developed an unusual technique. He would piece together several smaller sections of watercolor to assemble one large painting. The merging is so successful that it is almost imperceptible.

Looking at a few specific drawings from his early period, I was especially intrigued by the so-called “conventions for abstract thoughts.” These works purport to convey emotions; one is titled Dangerous Brooding, another Morbid Brooding, and a third Imbecility. They derive from Burchfield’s actual observations—either from nature, or his mind’s eye. In fact, emotions, like music, lack representational conventions in painting and drawing. Current researchers recognize “emotional synesthesia,” just as they do color-sound and other cross-modal manifestations. Synesthetic artists sometimes grapple with what they consider artificial distinctions between “reality” and “abstraction” and dreams.

One early painting, Church Bells Ringing, Rainy Winter Night (1917), contains anthropomorphic shapes and visual sound waves reminiscent of Edvard Munch’s notorious Scream of 1893. Indeed, two years earlier, on March 17, 1915, Burchfield almost echoed the Norwegian master’s own words in describing The Scream, when he wrote: “Noon is powerful—wind-whirled clouds dancing across a roaring sun.… The sunlight was so intense that I seemed conscious of a noise going on outside as of a weird singing shriek.” Like Munch, Van Gogh, and Kandinsky, Burchfield has at times been called an Expressionist. Other artists with whom Burchfield shares sensibilities include synesthetes David Hockney, Joan Mitchell, Carol Steen, and Marcia Smilack.

Paintings revealing Burchfield’s emotions, which ran the gamut from deep depression to ecstasy, far outshine his workmanlike studies of houses and construction sites mostly done during the 1930s. These include drawings and watercolors of the teens, and the triumphant masterpieces of the 1940s-60s. Many of the large, pieced together watercolors actually bear composite dates (examples: Autumnal Fantasy, 1916-44; Night of the Equinox, 1917-55;October in the Woods, 1938-63). A creative crisis in 1943 motivated Burchfield to return to his earlier paintings, reworking and adding to them. Many of the same “abstract” signifiers for emotions return throughout these paintings, as do his symbols for sound. For example, the small Song of the Katydids on an August Morning (1917) is filled with repeated black V-shapes that spring from the ground or fly through the air. Innumerable small, rounded arcs vibrate, thrum, and buzz from ground and trees. The sky emits larger, simpler, and calmer waves. And nature itself contrasts with human creation, as delineated in the regular horizontal and vertical lines of houses.

This show ranges from the “chamber music” of Burchfield’s small pencil or charcoal on paper drawings to huge orchestral landscapes; from soft, dreamy sketches to ecstatic outbursts that use thick paper to absorb his frenzied mixed techniques. Some works allude to specific music. One such, titled Rheingold, paradoxically a tiny (7 7/8-inch by 4 1/2-inch) drawing, dated March 13, 1915, paid homage to the giant Richard Wagner, one of the composers Burchfield most admired. The artist referred to this and a few others made especially for Wagner operas as “abstract hieroglyphics.”

Burchfield kept detailed journals throughout his life. On July 26, 1915, he wrote, “It seems at times I should be a composer of sounds, not only of rhythms and colors.” And again on October 15 that same year, “Walking under the trees, I felt as if the color made sound.” Later in his life, when recordings became available, he listened to the music of Jean Sibelius. On November 23, 1938, he noted parallels in his and Sibelius’s careers, saying it is “interesting to know that as a young man, he saw tones in terms of colors.” On December 18, 1963, he commented on two record album jackets he created for Mozart’s music, noting that he “made the backs yellow, because it seems to me his music is symbolized by that color.”

One of his many “doodles” (reproduced on Page 93 of the catalog) caused me to do a double-take. On it, Burchfield had written, in capital letters, “WINCENC,” and in smaller ones underneath, “Orchestra Conductor.” This was a reference to Joseph Wincenc, conductor of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and the father of Juilliard faculty member Carol Wincenc. Of course! Burchfield lived in Buffalo, and he obviously attended the ensemble’s concerts.

The Burchfield show complements two other musical events: the Christian Marclay “Festival” concurrently at the Whitney, and the Stephen Vitiello sound installation on the Highline, outdoors at 14th Street near 10th Avenue. Burchfield surely would have been gratified to find himself in their company.

“Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield” runs through October 17 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street; Wednesday, Thursday, Saturday, Sunday, 11 a.m.-6 p.m.; Friday, 1 p.m.-9 p.m.; closed Monday, Tuesday. (212) 570-3600; www.whitney.org.