Column Name

Title

The Museum of Modern Art is showcasing the murals Diego Rivera painted for it 80 years ago, and they are astonishingly relevant to today’s economic turmoil and political unrest. Highly acclaimed during his lifetime (1886-1957), Rivera and his work have suffered from neglect since his death. But this show goes the distance to help restore the great Mexican muralist’s reputation.

Diego Rivera, Agrarian Leader Zapata (1931). Fresco on reinforced cement in a galvanized-steel framework; 93 3/4 x 74 inches. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund.

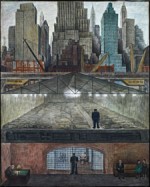

(Photo by © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)Diego Rivera, Frozen Assets (1931-32). Fresco on reinforced cement in a galvanized-steel framework, 94 1/8 x 74 3/16 in (239 x 188.5 cm). Courtesy of Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico.

(Photo by © 2011 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)Body

The current exhibition reprises one that opened in 1931, when the fledgling MoMA commissioned eight portable murals and provided the artist with a studio in its building to create them. At that time, retrospectives of individual artists were uncommon; this was only the museum’s second one (the first had been devoted to the then 62-year-old veteran Henri Matisse).

This show reunites five of the murals from the original display with three eight-foot working drawings, a 1930 prototype of a portable mural, plus numerous smaller drawings, photos, and illustrative materials.

There are a number of ironies surrounding Rivera and this exhibit. First: Rivera was an avowed and outspoken Communist, but his work was (and is still) supported by members of the Rockefeller family, among the wealthiest and most famous capitalists in history. Second: Rivera’s name was the one more people knew during the 1920s and ’30s, but the renown of his wife, Frida Kahlo, has far overshadowed his in recent decades. Third: Murals are meant to be painted on a wall for a specific public site, but these portable murals were designed to be hung in the museum’s galleries to be viewed by (for the most part) elite audiences. And fourth: Although known primarily for his Socialist Realist subject matter, Rivera had already achieved fame in Paris from his time as a Cubist (1911-21), and he retained many Modernist elements in his work.

The 1931 MoMA show drew unprecedented crowds; Rivera was one of the most celebrated and publicized artists around. Not coincidentally, he was a favorite of arts patron (and driving force behind the founding of MoMA) Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, which is one of the reasons her son Nelson Rockefeller suggested commissioning Rivera to paint a fresco on the theme of “new frontiers” opposite the entrance of the RCA Building (informally known as 30 Rock) in 1933. In case you don’t know the story, Rivera decided to seize this commission as an opportunity to pay homage to international Communism at the expense of one of the richest families in the world, substituting a head of Lenin for that of an anonymous worker in the mural, which he called “Man at the Crossroads.” The situation drew lots of media attention, and Nelson asked him to change the head back. When Rivera refused (and plans to move the fresco to, among other places, MoMA, fell through), the whole thing was destroyed. During the New Deal, which began a few years later, many artists paid tribute to Rivera in murals they painted (with federal funding) for post offices, schools, hospitals, and other public buildings throughout the United States. And Rivera subsequently re-created the Rockefeller Center mural in Mexico City, where it can still be seen at the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

In the early 1980s, the first major retrospective of Kahlo’s work was held outside Mexico City, and her fame soon eclipsed that of Rivera. Her work became ubiquitous as posters of her exotic self-portraits publicized museum shows, and in 2001, she became the first Hispanic woman to appear on a U.S. postage stamp. In 2002, a major motion picture,Frida, was released, directed by Julie Taymor and starring Selma Hayek (who was nominated for an Oscar for the role) and Alfred Molina as Rivera. Students today all seem to know of Kahlo, but few have heard of Rivera.

So, now it is time to even the score. There really never was an artistic competition between the two artists—their working styles have almost nothing in common. What is wonderful is that, thanks to this exhibit, we can now look with fresh eyes at Rivera’s murals. Not only are they timely in content, dealing as they do with social injustice and oppression, but their form is also incredibly contemporary. Rivera had, to be sure, lived in Paris, and been a thoroughgoing Cubist before he made his Socialist Realist murals, though he had always made use of Mexican motifs.

The themes of the murals in the show range from early Mexican history (Indian Warrior, Agrarian Leader Zapata, which is part of MoMA’s permanent collection, and The Uprising), to the three final works in the series, which depict labor and construction in Depression-era New York City. To me, the strongest—and most uncannily apropos today—painting of the New York City works is Frozen Assets (1931-32), which combines classical organization and Renaissance perspective (Rivera studied in Italy) with iconic 1930s motifs: the New York City skyline with its skyscrapers, cranes, and unprecedented explosion of building. At first glance, the mural appears similar to stereotypical 1930s works (many of which were influenced by Rivera), but there is something unique here. The painting is divided into horizontal sections. On closer inspection, the middle part of the painting is not just a dividing line, but, rather, masses of homeless people. They look as if they’re in the morgue—like so many sacks of potatoes neatly organized into rows. On top, the thrusting skyscrapers extend beyond the frame. And on the bottom panel, a few wealthy people and some guards congregate in a bank vault. Rivera makes literal the stratification of capitalist society: the rich support the building boom at the expense of the poor. Labor is exploited, the poor discarded, and progress comes at a huge cost to human life. Ironically, the construction site depicted in this painting is said to be that of Rockefeller Center, a few years before Rivera’s name would be forever linked with it.

Rivera’s portable murals succeed for the most part in balancing technique with subject matter, tradition with Modernism. While looking to the past, Rivera captured the present, and predicted the future. In many ways Rivera can be compared with the avant-garde artists of the Russian Revolution, with their combinations of machine esthetics, Modernism, and propaganda. In fact, he had spent nearly a year in the Soviet Union, starting in 1927, where the iconic filmmaker Serge Eisenstein acknowledged Rivera’s murals for their influence on avant-garde film. Both painter and filmmaker work in frames moving along walls; both are monumental, and made for mass audiences.

This eye-opening exhibit is just large enough to involve and educate viewers about mural techniques, American history, and the changing aesthetics in the history of art. It should not be missed.

“Murals for the Museum of Modern Art” runs through May 4 at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues. For museum hours and more information, visit moma.org or call (212) 708-9400.