Column Name

Title

On March 8, 1911, International Women’s Day was first celebrated in the United States. Sixty-seven years later, in 1978, this day was extended to a week; in 1987, Congress expanded the week to a month. And just in time for Women’s History Month 2009, I happened across “Worshiping Women: Ritual and Reality in Ancient Athens,” a most wonderful, memorable, and relevant exhibition at a relatively new venue, the Onassis Cultural Center, located on Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan.

Statuette of Athena (first half of second century A.D.), marble, Argos Archaeological Museum.

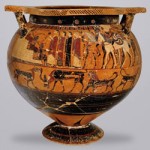

(Photo by Argos Archaeological Museum)Black-Figure Column-Krater (c.. 560 B.C.), clay, Vatican Museums.

(Photo by Black-Figure Column-Krater)White-Ground Lekythos (c. 490 B.C.), clay, St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Museum.

(Photo by © The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, 2008)Grave Stele of Polyxena (c. 400 B.C.), Boeotian limestone (so-called Thespian marble), Antikensammlung–Staatliche Museen, Berlin.

(Photo by Photo by Johannes Laurentius, © Berlin, Antikensammlung–Staatliche Museen)Body

It isn’t clear whether to put the emphasis on the first or second word of the title (“Worshiping Women” or “WorshipingWomen”), but it doesn’t matter. The exhibition addresses both interpretations; it features goddesses and heroines worshiped by the ancient Greeks, as well as demonstrating women’s roles as worshipers and priestesses. One of the exhibition’s stated purposes is to provide a corrective to the commonly held view that women had no voice in the ancient world. While it is true that they could neither vote nor hold office (and were certainly not “liberated,” in the modern sense of the word), women were nevertheless venerated by the ancient Greeks, and they played a central role in religious life.

The exhibition is large—it is divided into three parts—but not so big as to be overwhelming. It comprises 155 unusual treasures from nearly a dozen museums in Greece, as well as Europe and the United States.

Part One begins with portrayals of four principal goddesses: Athena, Artemis, Aphrodite, and Demeter (and her daughter, Proserpine). This section also includes a number of alleged heroines, women who mediate between the divine and the real (that is, they probably existed, but have been elevated over time to cult figures).

Part Two of the show features women who served as worshipers—both of gods and goddesses. This includes ordinary women who practiced rituals of libation and sacrifice, or who were involved in festivals, as well as priestesses. Women-centered festivals ran the gamut from the famous Panathenaia, celebrating the cult of Athena, and the lesser known Adoneia, in which women let down their hair and mourned the death of Adonis.

The third and last part of the exhibit, titled “Women and the Cycle of Life,” includes representations of real and ordinary women from critical stages of their lives. The focus here is specifically on marriage, childbirth, and death.

Looking more closely at a number of specific works, beginning with Part One: the intricate marble statuette of Athena from Argos (first half of the second century A.D.) lacks a head, neck, and both arms, but you scarcely notice that. She seems remarkably complete and self-contained, perhaps a Hellenistic reworking of a Classical model from about the fifth century B.C. We can observe the progression of the chisel marks from rough to smooth, emphasizing the graceful and rhythmical folds of the peplos (a sleeveless, tubular garment). Her curls reach down between the snake ornaments on her aegis (bib), and her belt is also snake-shaped. In her, we can see at least two aspects of the patron goddess of Athens; Athena was worshiped for her wisdom and her intellect, but also as a protectress in times of war.

A second goddess, Artemis, is painted in intricate detail on a lekythos (a narrow oil flask, c. 490 B.C.). Wearing an elegant, flowing garment called a chiton, she makes an offering to a swan, which lifts a foot as if in response. The exact meaning here is unknown, but Artemis was believed to be a cruel, warlike goddess, yet a protectress of virgins as well as women in childbirth. This lyrical example emphasizes the goddess’s more gentle side. She seems so modern that, from today’s perspective, it is hard not to be reminded of Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations, or of images of the dancer Isadora Duncan.

In Part Two of the show, one fascinating work is a very complex black-figure column-krater (a kind of vase used to mix wine and water, c. 560 B.C.). The painting consists of two registers, a top one with figures, identified by names written beside them, and the bottom one, panthers and goats. Most remarkable is the depiction of a priestess, with long black hair, in the act of spinning wool from a distaff, accompanied by two handmaidens and an old wet-nurse (her advanced age indicated by her white hair). The scene is a celebrated one from Homer’s Iliad in which Menelaus and Odysseus travel to Troy to ask for the return of Helen. Although the men are also shown here, their importance is clearly subsidiary to that of the priestess and her entourage.

From Part Three, there is the beautiful and mysterious marble grave stele (an upright slab with an inscribed or sculptured surface) of Polyxena. This is thought to be a depiction of a young bride, holding in her hand a miniature version of herself, which she would have offered to Artemis, goddess of marriage. It is not known whether the girl died as a child or right before her marriage. The Greeks thought it provident to supply her posthumously with ritual attire, so that she could perform this most vital function even in the tomb.

In considering the significance of this exhibition, we should remember that women in modern times have fought long and hard for suffrage and participation in the political life of contemporary nations, but they are still not accepted as priests and leaders in many religious sects. The idea of a female god, moreover, is even more foreign to most religions today. This sheds new light indeed on our perception of the role of women in ancient Greece.

In addition to the exhibition reviewed here, the Onassis Center promotes many cultural events, including art, theater, music, dance, lectures, and poetry readings. There will be a one-day international symposium on May 2 in connection with the present exhibition, which runs until May 9. Free tours of the show are offered every Tuesday and Thursday at 1 p.m. I highly recommend these. On the day I went, a graduate student in archaeology, Leslie Wallick, gave a most informative and delightful overview of the exhibition. (When you first enter the atrium of the Onassis Center, you can see an additional show: plaster casts of sculpture from the Parthenon, from a collection of the City University of New York.)

The galleries of the Onassis Center are located downstairs in a public space at 645 Fifth Avenue (with entrances on both 51st and 52nd Streets), and are open to the public, free of charge, Monday to Saturday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.