Column Name

Title

MoMA’s current show “Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925” is almost tailor-made for Juilliard performers and composers, as well as those of us in the liberal arts. It unites painting, drawing, and sculpture with music, dance, theater, and poetry, illuminating the myriad ways in which the performing and visual arts developed simultaneously during the formative years of Modernism.

Wassily Kandinsky, Impression III (Konzert) [Impression III (Concert)] (1911), oil on canvas, 30 7/8 x 39 9/16 inches.

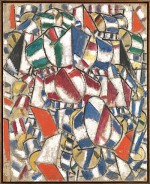

(Photo by Städtische Galerie, Lenbachhaus, Munich)Fernand Léger, Contraste de formes (Contrast of forms) (1913), oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 32 inches

(Photo by Museum of Modern Art)Body

That being said, no exhibition covering the vast territory that the Museum of Modern Art sets out to cover could possibly be complete. There are certain gaps—I’d like to see much more material about the effects of World War I as well as additional examples of music, dance, and theater. Paul Klee, that most musical of painters, is missing. And so is Joan Miró.

The curators, emphasizing that abstract art was not the creation of any one individual, reveal a complex network of interconnections. In the entrance to the galleries, a chart mapping some of these interrelationships resembles a century-old Facebook in which there are rarely as many as six degrees of separation. It’s fascinating to see who knew whom: Pablo Picasso, Wassily Kandinsky, Jean Arp, and Alfred Stieglitz are the unsurprising centers of social relationships, but a few unexpected artists such as Sonia Delaunay Terk (married to Robert Delaunay), Theo Van Doesburg of the Netherlands, and Russia’s Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova appear nearly as connected as the more familiar figures.

Upon entering the galleries, the first work one sees is Picasso’s Woman With Mandolin (1910). While Picasso never totally abandoned representation, here he went about as far as ever in the direction of pure abstraction. It’s almost impossible to discern the figure and instrument in this hermetic painting. Next you see Kandinsky’s Impression III (Concert) (1911), which he painted upon attending a performance of Schoenberg’s Second String Quartet, Op. 10, and you can hear a recording of the piece while you look at the painting. There’s also a case containing various stages of Schoenberg’s scores for the music. While Picasso never went further into abstraction, Kandinsky did. The large, Wagner-inspired Composition V—painted in December 1911, and shown in Munich in the Blaue Reiter Exhibition later that month—is considered a watershed work. From then on, Kandinsky never turned back to representation. These two paintings and his treatiseConcerning the Spiritual in Art influenced generations of artists to come.

One notable thread in the exhibition is that of “process” in the works of artists. For example, we are shown the sketches Kandinsky made that led to his Concert; these illustrate his progress from representation to abstraction. Likewise we get to see some steps Picasso took to arrive at his Woman With Mandolin. Further on in the exhibition, there is the instructive series of stages Van Doesburg underwent in order to get from a representational drawing of a cow to a painting inhabited by geometric forms no longer recognizable except as abstraction.

Another thread is the presence of the spiritual, mysterious, or ecstatic. Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, the Czech painter Frantisek Kupka, and others espoused theosophy and various metaphysical beliefs. This theme spills over to the other arts, such as modern dance. Mary Wigman, an innovator of modern dance, was excited by mystical and ecstatic ideas, as evidenced by her 1926 Hexentanz (Witch Dance). Wigman and her teacher and collaborator Rudolf von Laban are represented in the show by diagrams, sketches, and notations, as well as two early video performances. These appear toward the end of the exhibit, and seem to incorporate many of the techniques and threads of abstraction we’ve seen in previous galleries. Also of special interest to dancers and dance historians are five small drawings by the great ballet dancer Vaslav Nijinsky.

A third motif is the perpetual influence and inspiration from music, and the ways in which this most abstract of art forms steered visual artists towards pure abstraction. Although music plays at various points in the show, I found even more informative the numbers of artworks with music-related titles or that approximated music, including several paintings by Georgia O’Keeffe, photos by Stieglitz, and musical “equivalents” (works of visual art that use musical techniques such as counterpoint in color, lines, and shapes). These were by Kupka and also by artists in such post-Cubist styles as Italian Futurism, American Synchromism, and French Orphism.

Although there is not much in the way of theater in the exhibit, the works that are shown are quietly powerful. Mondrian’s painted wood Stage Set Model for Michael Seuphor’s “L’éphémère est éternel” (1926), struck me as incredibly modern and closely allied with his painting. Some Russian artists’ stage designs also demonstrate avant-garde ideas.

Film, a new art form during the period of this exhibit, is shown in the final galleries. Allied to the Dadaist and Surrealist movements, Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling limited themselves to abstract shapes, abandoning figuration in their moving pictures. Friedrich Kiesler (who was a production manager and scenic director at Juilliard from 1934 to 1957) was quoted in wall text as praising Eggeling’s totally nonobjective film Symphonie Diagonale.

Two strengths of the exhibit are that it is international in scope—the works are from Germany, France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Poland, England, Holland, Hungary, and the United States—and that it alternates the work of well-known and little-known artists. Comprising entire walls of Mondrian, Fernand Léger, Malevich, and Italian Futurists, it demonstrates clearly what ties these artists together, as well as relating them to American Synchromism, British Vorticism (another post-Cubist movement of this era, one which got its name from the poet Ezra Pound) and Russian Suprematism (a post-1915 movement that incorporated mysticism and grew increasingly geometric and minimalistic, culminating in Malevich’s famed White on White).

Sketches and studies accompany finished paintings while notebooks and journals of writers and painters fill cases throughout the exhibition. Among the most moving items is a notebook that French poet Guillaume Apollinaire made in an artillery-carriage compartment as a soldier during World War I. Here we see what he called calligrammes—poems written in the shape of the subject. In Pleut (Rain) the sentences literally rain down; in another, Lettre Ocean, the words form circles. These reminded me of Carlo Carra’s Patriotic Celebration, Free Word Painting (1914); in the show there is a study for Carra’s work, a painting/collage in which real and nonsense words spin out from an axis, evoking sounds of war, street signs, and cries. There was also a similar word circle by an Italian artist I had never heard of, Fortunato Depero. Wondering whether these artists knew each other, I returned to the wall chart at the entrance; they did. I found it equally fascinating to see who did not know each other. Mondrian, surprisingly, chose not to meet Picasso, according to the wall text, and developed his geometric forms independently of the master.

At the end of the exhibit there’s a separate gallery with a continuous playlist by Stravinsky, Varèse, Schoenberg, Ives, Webern, and Debussy that was compiled by the radio station WQXR. But it’s too little music for me—and not what I would have chosen. Plus, unless you already know the music, it’s hard to figure out what’s playing when. The curators point out that this may be the first time many museumgoers will be exposed to this “contemporary” music—I found it astounding that they referred to it as such since most of the music, like the art, is a century or so old!

It’s great fun to see the interconnections, influences, and processes of all these famous and nearly unknown artists. In this visual and intellectual feast that MoMA has served up, I’m sure you will make many discoveries of your own.