Column Name

Title

The name Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947) is inextricably linked with that of Igor Stravinsky. Although legend has had it that the vision for The Rite of Spring came to Stravinsky in a dream, history shows that it was actually Roerich’s idea. When the impresario Serge Diaghilev asked the set and costume designer Roerich to collaborate with Stravinsky in 1910, the artist agreed, suggesting to the composer two possible ballets: A Game of Chess and The Great Sacrifice. It was the second scenario, later to be immortalized as Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring), that Stravinsky chose. Groundbreaking and infamous, this work was to transform the history of music. Initially received with hostility and outrage, it soon became the icon of modernity.

Body

A documentary film shown on public television in 1989 (The Search for Nijinsky’s Rite of Spring) explores the research of an art historian, Kenneth Archer, and a dance historian, Millicent Hodson, that led to the restaging and reinvention of The Rite of Spring by the Joffrey Ballet. It is this film, seen by generations of Juilliard students, that inspired me to seek out the museum dedicated to the work of Nicholas Roerich. This small museum, located on 107th Street just off Riverside Drive, houses about 150 paintings dating from various periods of the artist’s life. It feels something like a shrine, containing artifacts of Asian art and antiquities as well as books and furniture that once belonged to the peripatetic artist.

Born in Russia, Roerich grew up in a well-to-do household, surrounded by music, literature, and the performing arts. His preferred art form from an early age was opera. Among the composers who inspired him were Borodin, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Wagner, Scriabin, Prokofiev, and Stravinsky. Although he never officially became a member of any group, he had deep affinities with the Russian avant-garde and Symbolist artists during the end of the 19th century, participating in many of the artistic and musical salons in St. Petersburg.

In 1906 Diaghilev arranged an exhibition of Russian paintings in Paris that included 16 by Roerich. By then, the artist had traveled a little in Europe, especially Paris. He took in only a few influences; we see some from Gauguin, some from Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and a couple of his paintings made between 1902 and 1906 seem related to Fauve painters such as André Derain and Henri Matisse.

Russia really took Paris by storm in 1909 (artistically, that is). On May 19, Diaghilev introduced the Ballets Russes to Paris’s Théâtre du Châtelet, with a spectacular performance of the “Polovtsian Dances” from Borodin’s Prince Igor, and two other dance suites. The combination of the virtuosity of Vaslav Nijinsky and Tamara Karsavina, the choreography of Michel Fokine, the wild exoticism of Borodin’s music, and Roerich’s splendid costumes and sets dazzled Parisian audiences. Five days later, the premiere of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Ivan the Terriblealso featured costumes and sets by Roerich. Of course, Roerich’s collaboration with Nijinsky and Stravinsky culminated in the extraordinary sets and costumes for The Rite of Spring. Indeed, he is sometimes referred to as the first artist auteur. Later it was Roerich who chose Martha Graham for the lead in the “Sacred Dance” in Leonide Massine’s 1930 production.

Roerich has been quoted (by Jacqueline Decter, in her book Messenger of Beauty: The Life and Visionary Art of Nicholas Roerich) as saying that he never painted scenery for an opera or ballet without first having a familiarity with the music. As he explained, “just as a composer … chooses a certain key to write in, so I paint in a certain key, a key of colour, or perhaps I might say a leitmotiv of colour, on which I base my entire scheme.”

In the entrance hall of the museum we see half a dozen small studies from 1944 for The Rite of Spring, commissioned by Massine for a later production that was produced posthumously at La Scala in Milan in 1948. The colorful, mystical, Russian-flavored studies share an affinity with early Kandinsky, without resembling them in the least. The essentialist view of nature in these paintings is expressed by the “keys” of green and blue, embellished with bits of red and yellows. Together with a number of other works, made in tempera on cardboard for the “Polovtsian Dances,” the small paintings in the entrance hall provide a kind of mini-retrospective. Roerich changed his original sketches a little after traveling extensively in central Asia, but the essence is the same as the earlier ones.

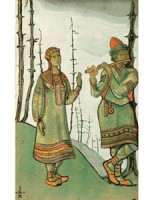

Upstairs there is a backdrop for the 1930 Rite of Spring; Yaroslava’s Tower Room (1914) for Prince Igor; and Snegurochka and Lel (1921) for Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Snow Maiden. The iconic maiden, Snegurochka, looks much like those in Le Sacre, with long braids, tilted head, decorated headband, and embroidery-edged dress. Standing somewhat awkwardly with her left hand raised, she listens to her beloved Lel’s flute playing. In the Russian story, she is an ice princess, daughter of King Winter and Fairy Spring. Yearning to be mortal in order to be with her shepherd lover, she melts into the streams of springtime. Behind the two stand bare trees and a hilly landscape. In a nod to classical antiquity, Lel resembles a Russian Orpheus; she might be Eurydice. All of these paintings depict Russian folktale fantasy with simplicity, geometry, and color.

Many other works Roerich did for the theater hang in the museum, including studies for Rimsky-Korsakov’s Maid of Pskov, Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, and plays by the Belgian symbolist Maurice Maeterlinck.

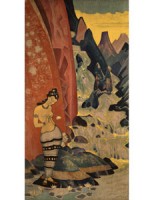

The 150 or so works in the museum represent only a fragment of the more than 7,000 paintings the artist produced. Of these, only a small number are direct studies for opera and ballet productions, but everything Roerich made has a dramatic presence. One especially evocative painting is a set of decorative panels created in 1920 for a private residence in London, but never installed there. Titled “Song of the Morning” and “Song of the Waterfall,” they stand 92 inches high and are part of a larger work the artist envisioned, called Dreams of Wisdom. The two exquisite paintings combine Gauguin-like simple maidens, but now Eastern (Indian) instead of Tahitian, with his own colors, wave-like mountainous backgrounds, clouds, and mystery.

One cannot speak of Nicholas Roerich without mentioning his extensive travels—first to Finland, then to the Himalayas and Mongolia. His quest was for spiritual enlightenment. Both he and his wife, Helena, wrote and taught about their own form of Theosophy. Many artists were drawn to the metaphysical philosophy popularized by Helena Blavatsky (1831-91) that sought a spiritual unity between human beings, nature, and all religions. The Roerichs particularly believed in the synthesis of the arts, science, and life. Indeed, in 1921 he founded a school in New York City called the Master Institute of United Arts, based on the same principle—all the arts united under one roof—as a school he had directed earlier in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1906-7 called the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts.

Although the Nicholas Roerich Museum is not well known, its following, as its director told me, is a fervent one. As well as receiving world respect for his art, Roerich earned the admiration of world leaders such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jawaharlal Nehru, and the famed poet Rabindranath Tagore.

The museum, located at 319 West 107th Street, is open Tuesday through Sunday from 2 to 5 p.m. and maintains an active schedule of concerts and poetry readings.

Images, from top: Maidens (1944) for Massine's production of The Rite of Spring; tempera on cardboard. "Song of the Waterfall" (1920) fromDreams of Wisdom; tempera on canvas. Snegurochka and Lel (1921) for Chicago Opera; tempera on cardboard. Old Pskov (1922) for Rimsky-Korsakov's opera The Maid of Pskov; oil tempera on canvas. Courtesy of Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York.