Column Name

Title

This spring would be a good time to visit the Brooklyn Museum. You could see both the gorgeous botanical gardens next door and the marvelous exhibition “Gustave Caillebotte: Impressionist Paintings From Paris to the Sea.” (Just hop onto the No. 2 train, and you come directly to the Eastern Parkway/Brooklyn Museum stop in less than 45 minutes from Lincoln Center.)

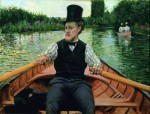

Gustave Caillebotte (1848–94): Oarsman in a Top Hat, 1877–78, oil on canvas

(Photo by Image courtesy The Brooklyn Museum)Gustave Caillebotte (1848–94): The Seine and the Railroad Bridge at Argenteuil, 1885 or 1887, oil on canvas

(Photo by Image courtesy The Brooklyn Museum)Gustave Caillebotte (1848–94): Oarsmen Rowing on the Yerres, 1877, oil on canvas

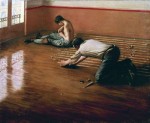

(Photo by Image courtesy The Brooklyn Museum)Gustave Caillebotte (1848–94): The Floor Scrapers, 1876, oil on canvas

(Photo by Image courtesy The Brooklyn Museum)Body

If you’ve never heard of Caillebotte, you are not alone. He is probably the least known of the French Impressionist painters. It’s even hard to pronounce his name (kai a buht, with an accent on the last syllable). His lack of renown is often attributed to the ironic fact that he was born into considerable wealth. Therefore, he has been considered a “gentleman painter,” and not taken seriously. Indeed, he became much better known as a collector of his fellow Impressionists’ paintings, which he donated to Paris museums. He also turned to boating and designing his own boats (models of some of which are in the exhibit, looking like modern wooden sculpture).

Once you have seen his work, however, you are not likely to forget it. I first learned of him in 1977 when the late Kirk Varnedoe (who became director of the department of painting and sculpture in 1989 at the Museum of Modern Art) introduced him to the public at a retrospective of his paintings at the Brooklyn Museum. Varnedoe was known for discovering and presenting lesser known artists and subjects. He had the most amazing eye around, and the brilliance to go with it. The 1977 Caillebotte exhibit was one of the most memorable I have ever seen.

Unfortunately, the most famous painting from that show—Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877), from the Art Institute of Chicago—is not in the current Brooklyn exhibition, but this lack is more than made up for by the vast number of dazzling paintings that are.

Caillebotte stresses “modern” life in Paris and its suburbs during the late 19th century. The show includes several paintings of men looking down at Paris streets from balconies, people on bridges, or simply the bridges themselves, and workers such as house painters and floor scrapers. All feature the master’s trademark dizzying perspectives, as well as his often sharp delineations between spaces. The close view can be clear and concrete, showing what’s happening at the moment, while what is beyond is often transformed into a dreamlike, softened blur.

His exquisite paintings of nature seem at first glance similar to those by other Impressionists, but they have a distinctly different appeal. Looking, for example, at the bold circles he drew in The Yerres, Effect of Rain (1875) was revelatory for me. Nobody—not even Cézanne—made such tangible geometric shapes. And they work; you hear, see, and smell those raindrops plopping into the river.

There’s a painting called The Pontoon of Argenteuil (1883), that is simply delicious, the houseboat-building with rowboats for rent, looking for all the world like a cake with pink icing, the pink picked up in nearby boats and far-off rooftops.

Oarsmen Rowing on the Yerres (1877), used for the cover of the catalog and reproduced in color in a recent New York Times review, is extraordinary in the way it takes the viewer inside the boat with the rowers. It is reminiscent of the Met’s 1874 Boating by Manet, as well as the Japanese prints that influenced them both. But with Caillebotte, we become more part of the boat, pulling the oars together with the strong rowers. (Manet’s man and woman are relaxing and looking pretty in the sailboat.) In other paintings of rowers, the artist makes them look almost like robots, skimming their skiffs along the Yerres River.

One painting, a close-up of an Oarsman in a Top Hat (1877-78), depicts an upper-class gentleman who has taken off his suit jacket and laid it beside him on the seat; no doubt he has worked up a sweat in the effort of rowing. His triangular form in the boat dominates the picture plane, dwarfing everything in its wake. I always think of this as a self-portrait, though it’s not labeled as such.

Other scenes show alienation caused by modern industrialism, like the small square with cut-off figures of people in A Traffic Island, Boulevard Haussmann (1880). This reminds one of Degas’s Place de la Concorde (1875), but whereas Degas accents human beings, Caillebotte makes the tiny figures seem so far off, the whole thing is almost like a dream.

Interior, Woman Reading (1880) shows a close-up of a seated woman reading a newspaper; her husband, lying down on a sofa far behind her, also reads a paper. At first the picture looks innocuous—just a relaxing bourgeois day—but the work became known as “Woman With the Little Husband.” The perspective made him appear so tiny that he could almost be held in the palm of her hand. It looks a bit like Mabou Mines’ recent production of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House in which the men are midgets and the women nearly six feet tall. This was not lost on contemporaries who condemned it—or admired it (J.K. Huysmans, author of the vastly popular Against the Grain, was an admirer). A Doll’s House was published in 1879, the year before this picture was painted—probably a coincidence, but certainly a symptom ofZeitgeist.

Reviewers in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and elsewhere have disparaged Caillebotte’s later paintings, but I thought that his apple trees look like Van Gogh before Van Gogh did them. His seascapes are reminiscent of Whistler. And I don’t think that the riot of colors and brushstrokes in his garden paintings (in the last room of the exhibition) has been outdone by anyone.

The artist’s pure joy in paint, color, brushstroke, and perspective; in Paris, the river, the boats, the weather, and humanity, is all there—everything that has made Impressionism the best loved and most accessible art movement worldwide. But there is something else, too. Is it the immediacy? The unusual angles? The freshness? The variety? Perhaps it is just the newness—to me. I am frankly tired of the same old Monets, Renoirs, Pissarros, Sisleys, even Degas and Whistlers, no matter how beautiful they are. But Caillebotte’s paintings provide new and different ways to view these familiar scenes. They are at the same time more solid, more rooted in naturalism, but more avant-garde, in pointing the way towards photography and abstraction. They are so strong they even look beautiful in reproductions.

The show continues at the Brooklyn Museum through July 5. The museum is open Wednesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday from 11 a.m. to 6 p.m.; it is closed on Monday and Tuesday.