Column Name

Title

The Julia Margaret Cameron exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art has only 35 photographs, but it evokes a world abundant in Romantic poetry, high drama, Madonnas, nymphs, and witches. What makes this so remarkable is that Cameron, who lived from 1815 to 1879, used real models to depict fantastical scenes, and an unwieldy box camera rather than a paintbrush. Moreover, she processed her own photos, which was time-consuming, arduous, and often dangerous. Some have criticized her “sloppy technique,” but it is clear that she aspired to create painterly and sculptural effects in her work.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 5. For more information, go to metmuseum.org or call (212) 923-3700.

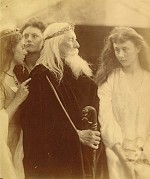

The Parting of Lancelot and Guinevere (1874); albumen silver print from glass negative

(Photo by Metropolitan Museum of Art)King Lear Allotting His Kingdom to His Three Daughters (1872); albumen silver print from glass negative

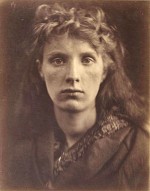

(Photo by Metropolitan Museum of Art)The Mountain Nymph Sweet Liberty (1866); albumen silver print from glass negative

(Photo by Metropolitan Museum of Art)Body

The artist only began taking pictures in 1863, when, at the mature age of 48, she received a camera as a gift from one of her six children. While that daughter had presented her mother with the camera as an antidote to boredom, Cameron never considered photography a mere hobby. “My aspirations,” she wrote in a statement quoted in the catalog, “are to ennoble Photography, and to secure for it the character and uses of High Art by combining the real and ideal and sacrificing nothing of the Truth by all possible devotion to Poetry and beauty.”

At the Met show, the curators have divided Cameron’s work into portraits of great men and women plus staged groupings. Among the men included are her close friend and sometime neighbor Alfred, Lord Tennyson, the scientist John Herschel, and the philosopher Thomas Carlyle. Among the women are relatives, neighbors, and models she hired—she often portrayed them in literary, historical, or biblical roles.

One of my favorite photos in the Great Men section is of Joseph Joachim (1831–1907), the famed Hungarian-born violinist, who was a close friend of Brahms, Liszt, and Robert and Clara Schumann. Cameron asked him to sit for her and in the photo, just his face and large hands are lit; his body was immersed in dark shadows. Shot in profile, Joachim looks off-camera, and the triangular composition reflects Cameron’s knowledge of classical Italian Renaissance composition.

In the Women section, The Mountain Nymph, Sweet Liberty (1866), contrasts strongly with the noble, carefully coiffed Joachim. This model, a Miss Keene (her first name has been lost), stares directly at us. Cameron’s title comes from a verse in John Milton’s poem “L’Allegro”:

Come, and trip it as you go

On the light fantastic toe;

And in thy right hand lead with thee

The mountain nymph, sweet Liberty

The model’s tousled hair and somewhat wild look suggest a mountain nymph, but for me Cameron’s Nymph seems almost too real and fraught. It is interesting to contrast it with the totally different, lighter spirit of George Frideric Handel’s 1740 musical setting of the same Milton poem.

One of the most striking of her staged groupings features her patient, white-haired, white-bearded husband (who was 20 years her senior) as King Lear, and three sisters—Lorina, Elizabeth, and Alice Liddell—acting out this tableau vivant. Cameron has dressed the two evil and deceptive sisters, Regan and Goneril, gorgeously. Lear trusts these duplicitous daughters but disinherits and casts aside Cordelia—the only one of the three who turns out to be honest and loving. Alice Liddell, dressed simply in white, takes this role, representing Cordelia as the epitome of Pre-Raphaelite innocence. (Seven years earlier, a professor named Charles Dodgson—pen name Lewis Carroll—told the Liddell sisters a story that he later wrote into a book called Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and his numerous, sometimes suggestive, photos of Alice and her sisters have been the source of much speculation for years.)

This third section of the exhibition includes Cameron’s illustrations for Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, including a photo of the lovers Lancelot and Guinevere. Also in this section are depictions of Circe and Sappho; there’s also an Annunciation influenced by Italian Renaissance painter Pietro Perugino (1469-1523).

This exhibition shows the early stages of photography, and the many ways in which it imitated painting and sculpture. In some senses, photography has come full circle in the 21st century. Art galleries today are as likely to feature staged, often melodramatic photos and photo installations as paintings.

Most of us now take it for granted that photography can be high art. However during its formative years—and even up until the 1960s—it was generally denigrated by the art history establishment as merely a mechanical means rather than an art form even though Cameron and others had elevated photography into the art form we recognize today.