Column Name

Title

Subhead

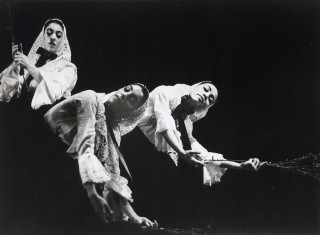

Martha Clarke (left) in the Juilliard Dance Ensemble’s performance of Doris Humphrey’s Ritmo Jondo in Februrary 1965. She’s shown with Ze’eva Cohen (center) and Lourdes Puerollano.

(Photo by Milton Oleaga; Juilliard Archives)In Angel Reapers, the bizarre utopia of the Shaker community is conveyed through rhythm, a cappella singing, and movement sequences. A collaboration that blurs the lines between drama, musical theater, and dance, Angel Reapers was created by playwright Alfred Uhry and Martha Clarke (BFA ’65, dance) more than a decade ago and first seen in New York City in 2011; a reworking of it was at the Signature Theatre this winter.

Body

Clarke, the recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant, N.E.A. and Guggenheim fellowships, a Drama Desk Award, two Obies, and many other industry plaudits, is known for her collaborations with artists from a variety of disciplines as well as her interpretations of a vast range of subjects. Before turning to choreography, she was a founding member of and danced with Pilobolus and Crowsnest.

After attending a performance of Angel Reapers, first-year dancer Moscelyne ParkeHarrison interviewed Clarke about her collaborative efforts, her influences, and the artistic foundation that she began to establish at Juilliard.

What intrigued you about the Shakers?

When Alfred Uhry approached me with this idea [about a decade ago], I had never worked with an American subject though I live in an old house in northwestern Connecticut [near where the Shakers were based]. I find the Shaker aesthetic both in music and architecture very beautiful and moving. The life of Mother Ann Lee, the founder of the Shaker movement, seemed a rich subject to investigate in song, dance, and text. It was a utopian society founded by a woman!

How do you balance your vision in a process with another artist?

I choose a collaborator mostly by instinct. I like to work with people whose company is enjoyable and stimulating, and I look for challenge, generosity, and mutual respect. It’s important to feel any collaboration will enhance the work, not diminish it. Process is often the most rewarding time in creating new work. There are surely difficult days, but wonderful epiphanies as well. It’s always an adventure.

What do you look for in a collaborator?

I work with people I admire, trust, and share a sense of adventure. I also like to have fun!

What do you look for in a dancer?

I go on instinct, but facility, charisma, intelligence, and a general openness are important elements when casting a role or developing a company. My work is kind of hybrid; it’s generally cross-disciplinary with combinations of dancers, actors, singers and musicians.

How has your creative process changed in your years of choreographing and directing?

I’m now more interested in character than in steps, and I emphasize clarity of subtext more than invention of movement. I’m an ardent fan of film, and I think my stage work has been deeply affected by years of looking at great screen acting and directing and the use of space and light.

What intrigues you about making dances influenced by historically charged subjects or works of art?

I choose subjects that fascinate and challenge me, and I like creating work that has a strong sense of atmosphere. I love the research actually. Some subjects that have captivated me have been Vienna at the turn of the 20th century, The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymous Bosch, Kafka, Chekhov, Pirandello, German lieder, and Colette’s Chéri. [Clarke’s multidisciplinary work based on Colette’s novella played at the Signature in 2013.]

How did Juilliard influence your collaborations with artists of other mediums?

I had a few very influential teachers. Louis Horst (faculty 1951–64) taught choreography, and he introduced very basic ideas: how to look at art, listen to music, and be open to influences from history. He taught structure and style. I also had an invaluable education in music history, which has supported every piece I have done. Many of the skills I learned at Juilliard of course, are now integrated in much of my work.

What was it like to work with such dance giants as Anna Sokolow and Antony Tudor?

Anna was severe and critical. I learned a lot from her, but I left her company after a few years as there was no sense of play or fun. I worked with Tudor at Juilliard, and he too could be caustic and hard, but he was brilliant, ironic, and very funny. I worshipped him. Both Tudor (faculty 1951–71) and Sokolow (faculty 1957–93) have had a very strong impact on my work. Sokolow opened my eyes to heightened theatricality and a less-is- more aesthetic. I was fortunate to study ballet with Tudor, and his work inspires me to this day. He was a great storyteller, and my interest in character and emotional subtext was definitely informed by love for his ballets. His musicality, romanticism, and sense of psychological motivation has always been important to me.

What projects are on the horizon for you?

I am beginning research and work on a new piece based on the life of St. Francis. I loved studying medieval and early liturgical music at Juilliard, so I have come full circle! The other new work is a song cycle for Michael Stuhlbarg (Group 21) based on the outsider artist Henry Darger. Composer Stewart Wallace, playwright David Grimm, and designer Julian Crouch are my collaborators. I also have two older works I hope to remount: a play I created with Christopher Hampton based on the relationship of Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddell that was performed at London’s Royal National Theatre more than 20 years ago, and Charles Mee and I are also looking for an opportunity to restage Vienna: Lusthaus. No slowing down!