Title

Subhead

As he begins the second year of his two-season residency at The Juilliard School, Maestro James Conlon is slated to conduct a newly conceived trilogy of rarely performed one-act operas by Modest Mussorgsky, Ernst Krenek, and Benjamin Fleischmann. Directed by James Marvel in his Lincoln Center debut, the venture combines Conlon’s Recovered Voices project with his desire for innovation in opera programming, as well as with an exploration of the art of the miniature, in what Conlon calls an “experiment in opera theater.”

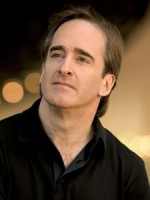

James Conlon will conduct Trilogy, an evening of three one-act operas about marriage.

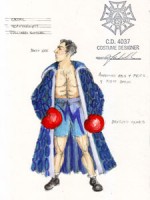

(Photo by Ravinia Festival/Todd Rosenberg)James Marvel will direct singers from the Juilliard Opera Center in Trilogy.

(Photo by James Marvel)Body

Inspired by the model of the instrumental recital, Maestro Conlon says that he structured the trilogy on the concept of coherence and variation—that works performed together can present not only contrasting styles but also unifying ideas. While opera productions usually present a single work in an evening, Conlon enthusiastically challenges this routine and, as he said in a recent e-mail interview, feels that “there is much exploration to be done in presenting short operas in interesting combinations. This approach would bring attention to works that otherwise might not see the light of day.”

According to Conlon, the amalgamation of the particular works that make up Trilogy evolved out of his own lifelong desire to see Mussorgsky’s uncompleted opera, The Marriage, on stage. Having discovered a recording of the piece during his high school years, he says he fell in love with the work immediately despite not being able to locate a score. When he finally uncovered one in 1988 while performing Khovanschina, another Mussorgsky work, at the Metropolitan Opera, Conlon vowed to bring it to life.

“My many years spent conducting and studying Mussorgky’s other large-scale works” as well as those of other Russian composers, explains Conlon, “made something quite clear to me. Mussorgsky’s theories proposing the spoken Russian language as the cornerstone to a new musical language not only transformed Russian music, but they deeply affected Western European music as well. The Marriage became apparent to me as Mussorgsky’s seminal work.”

However, due to its brevity, Conlon had to find the ideal complementary work or works in order to make The Marriage a staged reality. Benjamin Fleischmann’s opera Rothschild’s Violin came next to the grouping. While Fleischmann could be connected “as a spiritual grandson of Mussorgsky through his teacher, Shostakovich,” explains Conlon, “I was also drawn to him as a victim of the Nazi regime. He was killed in 1941 in the siege of Leningrad at age 25 before he could even finish the work.” In a tribute to his pupil, Shostakovich finished the opera in 1943, though it was banned after its first performance due to the opera’s setting in a Jewish shtetl.

Even with this pairing, Conlon was still unsettled. “Something was not right,” he says. “I wanted a concise, tautly constructed, 90-minute program. The bookends were there, but I needed a centerpiece.” Through his search, Conlon gravitated to the works of Ernst Krenek, who was also a target of Nazi oppression.

In order to select the most appropriate Krenek work, Conlon mused over the already existing musical connections (Mussorgsky and Fleischmann) and historical ones (Third Reich despotism). In addition, there were Russian literary links: Mussorgsky’s satirical libretto draws its inspiration from Gogol, and Fleischman’s Rothschild’s Violin presents a realistic and heartrending depiction of the poor derived from Chekov’s play of the same name. What was missing, explains Conlon, was the bridge in the three-part architecture, between “a humorous first movement and an expansive apotheosis for the finale.” The work Conlon finally chose is Krenek’s Heavyweight, or The Pride of the Nation. His trilogy complete, Conlon combines the humorous, the lighthearted, and the tragic in a continuous, three-part social commentary unified by what he calls a “dramaturgical link.”

Thematically, all three operas address marriage in its various stages, “before, during, and at its end—the preparation, the early years, and then the last,” as Conlon clarifies. The plot of the Mussorgsky-Gogol satire depicts the humorous musings of a minor member of the Russian bourgeoisie as he plans, and then flees from, marital bliss. Krenek’s burlesque and satirical operetta portrays, through a commentary on the nouveau riche, the conflict between a cuckolded husband—the boxing champion Adam Oxtail—and his cheating wife. Finally, Fleischmann’s sad tale tells the story of bittersweet transformation in a poor coffin maker whose wife dies.

But while the operas all address marriage, as director James Marvel explains, “the important thing with this grouping of shows was to identify the deeper connections and themes—the themes that go beyond the most obvious aspect of them all being about marriage. Once I had realized, for example, that Shostakovich, a longtime admirer of Mussorgsky, had also been exposed to the music of Krenek and that Krenek’s music had influenced Shostakovich’s own style of composition, I was intrigued and exhilarated. All of a sudden, I began viewing the pieces as a sort of conversation or ‘trialogue’ amongst three great composers, rather than as three separate entities that happened to address a similar theme.”

Also a fond proponent of thinking outside the box, Marvel, in his approach to conceiving stage works, displays an alchemy of the traditional and psychological that will be evident in this production. In his opinion, the physical set designs should not just reflect the music but be “an outward manifestation of it. When done to perfection, the two should be indistinguishable from each another.”

About the upcoming production, Marvel, a violinist as well as an actor and director, writes, “In Trilogy, we move from the ambivalent bachelor of The Marriage to the marital infidelity of The Heavyweight and end withRothschild’s Violin, in which an aging widower measures his life in losses. Essentially, Trilogy depicts three households in an ever-expanding universe.” He has tangibly represented this world expansion in the set with a house-shaped portal that increases in size with each work, symbolizing the audience’s own expanding historical and thematic understanding. Marvel added, “Also, it would have been irresponsible not to consider the political climates in which these pieces were written. It would have been irresponsible not to consider the art and architecture prevalent during that time because art and architecture are inherently political. I believe that you should be able to see the composer, his music, and his politics when you look at a set, and I believe we have been successful in capturing all three.”

Brian Zeger, artistic director of Juilliard’s Vocal Arts Department, says it is the broad spectrum of styles that makesTrilogy such a great opportunity for young singers. “Many of our performers are encountering these styles—not to mention the Russian language—for the first time,” he explains, “so the possibilities for learning are tremendous.”