Title

In January 2012, the Focus! festival celebrates the centennial of John Cage, which is a sign of the tremendous changes that have taken place at Juilliard in the past 40 years. Whereas any celebration of Cage was unthinkable when I started teaching here, in 1970, my first mention of this idea last spring brought an immediate and enthusiastic response from President Joseph W. Polisi and Dean Ara Guzelimian. As the word got out, students in large numbers asked to be part of it. Cage would have been pleased. He wanted his ideas to be understood, and he loved to teach open-mindedness to anyone who cared to listen. Whatever one thinks of his compositions—opinions are widely divergent—he earned the worldwide attention that he received. His magnetic personality, intellectual brilliance, adventurousness, articulateness, incredible mischievousness, and gentleness of spirit are unforgettable to those who knew him. One of the few things that made him unhappy, however, was having to deal with performers who played his music without attempting to understand his aims and without putting their best energy into the performance. His music is very easy to ruin if played in an inappropriate spirit.

John Cage is the subject of Juilliard’s 28th annual Focus! festival, which opens on January 27, 2012.

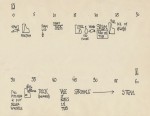

(Photo by Rhoda Nathans)A page from Cage’s Water Walk for Solo Television Performer, which is scored for, among many others (with Cage’s punctuation), “3 tables, 1 Bath tub (3/4 filled), 1 Toy Fish, 1 Grand Piano with lid removed, 1 Explosive Paper Bottle (exploded by pulling a strong) which ejects confetti (not bits of paper, but streamers), 1 Electric Hot Plate, 1 Pressure Cooker with hot water, 1 Toy Rubber Duck which sounds when squeezed, 1 Dozen Red Roses (fresh or artificial),

1 Electric Mixer (with ice cubes in it), 1 Turkish cymbal, 5 Portable radios of inferior quality, and 1 Goose Whistle.

Body

My own acquaintance with Cage illustrates his multifaceted personality. Our first encounter took place in 1972, in preparation for a retrospective of his work by Continuum, the new-music ensemble I co-direct with Cheryl Seltzer. At a rehearsal of Amores (for percussion and prepared piano), I was very impressed by his superb ear for detail, and pleasantly surprised when he advised me to play the prepared-piano solos “like Chopin”—especially by using rubato as needed. It became clear to me that anyone who claimed Cage knew nothing about composing probably had not heard much of his music.

Our second encounter, shortly thereafter, was my earliest exposure to Cage’s incredible mischievousness. I was conducting Continuum in a piece that could not have been more different from Amores, or from anything else, for that matter: Imaginary Landscapes No. 4, for 12 radios, 24 performers, and conductor, a composition whose sound is absolutely random. During a lunch break, Cage suddenly said to me, “That’s a really funny piece, isn’t it?” I replied that he surprised me, because I always thought of it as a serious study of the beauty of unrelated sounds. He agreed, but added, with his infectious smile, that it was really funny to watch the conductor leading all the ritardandi, accelerandi, and tempo changes, while the sounds coming out of the radios bore no resemblance to the conducting. Of course, the piece is hilarious, and keeping the players’ demeanor serious is always a challenge for the conductor. In this case, the players were doing their best, but, unable to suppress their giggles, they risked ruining the piece like mediocre comedians who laugh at their own jokes. When the rehearsal resumed, I asked Cage to say something about the piece. After emphasizing its seriousness, he broke into a loud guffaw. From then on, there was no problem with random smiles or chuckles from the players, even at the concert, when the audience was roaring.

Cage’s fusion of serious musician, philosopher, and prankster came back to me as I went through virtually all of his compositions to try to grasp what a Cage festival ought to contain. It became clear that he had more-or-less three distinctive creative phases. In the first period, from the early 1930s to the late 1940s, he produced a large number of extremely beautiful, fully composed compositions, largely using piano, prepared piano, voice, and percussion ensembles, with a handful of pieces for other instruments, climaxing with the monumental Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano. This early music is, in general, extremely gentle and lyric, reflecting his dual loves, Satie and Webern. His astonishing, trancelike solo piano piece In a Landscape (1948) has proved over and again to make a bigger impression than the big, virtuosic, piano solos that are staples of recitals. Many of Cage’s early works manifest his interest in a core belief, imparted to him by his teacher Henry Cowell, that if one wants to compose systematically, one should invent one’s own systems, not simply adopt those of others (such as the 12-tone method). Cage did just that, exploring systems as diverse as his personal adaptation of Schoenberg’s method, and rhythmic systems derived from Indian music, one of the many non-Western cultures to which Cowell had introduced his students.

After the late 1940s, stimulated by his studies of Zen Buddhism, Cowell’s teaching, and his own boundless curiosity, Cage began his search for a way to compose that was entirely detached from what he considered the contamination of personal taste. To do it, he worked systematically at randomizing materials, apparently an oxymoron but actually quite logical, since a tightly controlled system would resist distortion based on taste. His methods became more and more determined and extreme; “compositions” were sometimes no more than instructions, some detailed, sometimes vague, that were to be used to create a piece. Many of them resulted in music that sounded so similar to the predominant disjunct style of the 1950s through 1970s that it almost seemed irrelevant whether such music was truly composed or truly random. Of course, there was a big difference, but the untrained listener sometimes could not tell the difference. The works of that middle period are often straddle the border of music and theater, climaxing with Cage’s amazing operas, Europeras 1-5 (1988-92), which summarize his ideas up to that time.

By the time he wrote the operas, Cage was already moving toward his late period, in which his music is often fully written-out even though he may have used randomizing methods to generate it. The gentleness, lyricism, and sonorousness of the late works, which he wrote during the 1980s up to his sudden death in 1992, gives them an almost “normal” feeling because of the sheer beauty of composed sound, and they certainly reflect a return to his earlier years.

This year’s six Focus! concerts attempt to represent Cage’s multifaceted musical personality as fully as possible. The challenge is great, to be sure. Some compositions, such as those involving entire cities, “prepared train,” or other site-specific needs, are beyond our means. Many middle-years compositions require a lot of technical support or outmoded technology (obsolete electronics, wind-up Victrolas). Even finding radios to perform Imaginary Landscapes No. 4 has been challenging as audio control systems have changed so much as to make the piece almost impossible. Problems of obsolescence aren’t new—and they certainly amused Cage. In the 1950s, when the historical performance movement was gaining steam, he wrote Cowell that the recent discontinuation of certain types of screws made it impossible to perform his prepared piano music as he had originally intended! Reading the letter decades later, I could imagine him laughing as he wrote.

The festival’s six concerts will take place in the Sharp Theater, Paul Hall, and Alice Tully Hall. In contrast to many Cage festivals, which seem to favor music by Cage’s friends and followers, Focus! 2012 will be devoted almost entirely to him. The two exceptions will be heard on the January 30 concert by the Juilliard Percussion Ensemble. Its director, Daniel Druckman, argued persuasively in favor of celebrating Cage’s place in the percussion revolution by including one piece by Cowell (Ostinato pianissimo) and one by Cage’s friend and fellow Cowell pupil, Lou Harrison, the Concerto for Organ and Percussion. The final concert in the festival, by the New Juilliard Ensemble, includes the rarely heard score for the ballet 1947 The Seasons, the Concerto for Prepared Piano and Orchestra (1950-51), and Concert for piano and ensemble (1957-58), in which the members of the ensemble play their own parts (or parts of their parts) without any mutual interaction or coordination. The other four concerts will include a mixture of chamber, solo, vocal, and theatrical compositions. A symposium will precede the concert on January 31.

Focus! 2012 should be an excellent opportunity for both those who have heard of Cage but never heard his music, and those who are fascinated by him and want to hear more.