Title

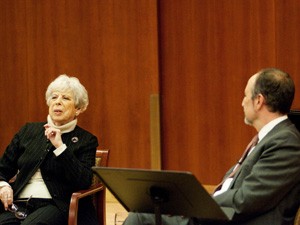

Music faculty member Pia Gilbert spoke about her career and personal history with Dean Ara Guzelimian in a recent doctoral forum.

(Photo by Chris Downes)On January 19, the Juilliard community was afforded a unique opportunity to hear a firsthand account of history at the third doctoral forum of the academic year. The topic of the evening was “Pia Gilbert and Her World of Fellow European Émigrés in Los Angeles,” structured as an interview between Gilbert, a longtime music faculty member, and Provost and Dean Ara Guzelimian.

Body

Born Pia Wertheimer to a Jewish family in 1921 in Kippenheim, Germany, Gilbert described an early “addiction” to music that has prevailed throughout her life. She sharply contrasted the accessibility of music and media today with the days of her childhood, when recordings and radios were not readily available. She remarked tellingly, “I never heard an orchestra play Beethoven symphonies until after I played them [piano] four-hands with my mother.”

Only 12 years old when the Nazi regime came to power, Gilbert said the whole system seemed to change overnight. One day, she said, “We went from first- to second-class citizens and then to no-class citizens. We had zero rights. We were just lucky to be alive and hope to get out.”

With an affidavit from her mother’s aunt, she and her family emigrated from Germany to New York in 1937. She attended George Washington High School, in the Washinton Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, receiving a medal in music. Because of the concentration of refugees living there, she said people referred to that area as the “Fourth Reich.” Eventually, Gilbert attended the New-York College of Music and was conferred an Artist Diploma in piano.

Despite her training as a pianist, her entry into a life in music was not conventional; instead, she launched her career through the world of dance. By working with artists such as Martha Graham, Lotte Goslar, Doris Humphrey, and Louis Horst, to name a few, Gilbert became a respected accompanist for dancers and choreographers. As she grew increasingly involved in both the ballet and modern dance scenes, she said she not only “began to be able to distinguish between the two dance forms, but also between the people, even while simply riding on the subway.”

Eventually, her marriage brought her to settle in Los Angeles, where she resided from 1946 to 1985. Her renown as a pianist led to an offer from the University of California, Los Angeles to be an accompanist for dance classes and ultimately, to develop a course for teaching music to dancers. There, she created “The Gilbert Method,” which taught dancers how to become musically literate—how to read a score and how to analyze music.

During the forum, Gilbert described 1950s Los Angeles in the aftermath of World War II. With an astounding collection of artist émigrés, the city became home to many musicians and writers. Described by Dean Guzelimian as a “world removed,” Los Angeles seemed to represent a “utopian dream” for these artists because of the promise of Hollywood, and also because of the beautiful weather, ocean, and palm trees. Though some enjoyed the challenge of the “frontier,” that is, the scarcely established cultural scene and the difficulty of generating concert series and programs, Gilbert said that the musicians seemed to have an easier time assimilating than writers. While writers faced the barrier of English, “Musicians and composers could speak music in any language.” She also recounted how the émigrés built their own ghetto in Los Angeles and joked that she learned better German there than in Germany.

In California, Gilbert was directly associated with many prominent artists, perhaps most notably with the Schoenberg family. Despite the feud between Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky, she was also close to the Stravinsky family.

Gilbert’s interview was filled with anecdotes of her personal experiences with the artists she said became like her “extended family,” such as the Schoenbergs and Stravinskys, Bruno Walter, Alma Mahler-Werfel, Nicolas Slonimsky, Ernst Toch, Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger, and Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, among others. Her stories were at once charming, humorous, and poignant, painting a detailed portrait of the richness of personality and culture of this historic place and time.

Observing how linked all of these artists were to one another, Dean Guzelimian commented, “You can begin to see how this entire community became populated by these deeply interconnected, deeply cultured histories and artistic families.”

In the final segment of Gilbert’s interview, she discussed her lifelong and “profound friendship” with composer John Cage and his partner, choreographer Merce Cunningham. In her friendship with “those two giants,” her two lives of music and dance were truly intersected.

Gilbert, who is also a composer, said that throughout her career, she learned “a lesson of openness and curiosity.” Taking the best experiences from her life in music, dance, and theater, she not only developed her own musical individuality, but also experienced an ease traveling among all of these worlds without having to be partisan to a particular concept or style.

Though her courses are not being offered this year, fortunately for Juilliard students, Gilbert will teach again next semester. As Dean Guzelimian—who has known Gilbert since his days as an undergraduate at U.C.L.A.— told The Journal in a recent interview, “When she teaches these topics, it is not out of library research. She is talking about it from her own life experiences.”