Column Name

Title

Subhead

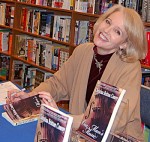

Christina Britton Conroy (Pre-College ’67) didn’t plan to be an entrepreneur. “I just set out to make a living as a singer—like every other Juilliard student, you think people are going to pay you to do your art for the rest of your life, but it doesn’t always work out that way,” the singer/

actress/novelist/music therapist told The Journal. Despite having run a successful nonprofit for almost a decade, Conroy doesn’t think that being an entrepreneur and a musician are complementary. “I don’t think creative artists are generally good at doing business. I happened to have learned to be good at it, but I would much rather have someone I trust do the business end and I would be creative and do art.”

Body

That said, Conroy—perky, professional, and enthusiastic—is every inch a show person, and that comes out in all her work. In 2004, after working as a music therapist in various social service organizations and schools for a decade and a half, Conroy founded Music Gives Life, the organizational home for ShowStoppers, a group of seniors who perform in nursing homes, houses of worship, and schools—wherever they’re invited—all over the city.

Prior to ShowStoppers, “I’d been doing all the musical therapy things—musical improvisation groups, chorusing along,” Conroy said. “But then some of the seniors I was working with said, ‘You know, this improv stuff is really fun, but we’d really like to play real music. We’d like to start a band,’” she recalled. “And I swallowed real hard, because these people were not terribly musical. They were all over 60 and many were in their 70s and 80s, and they’d never played a musical instrument—but they wanted it, so we did it.” The first thing she found was that there were no off-the-shelf arrangements she could use—“I needed very simple arrangements,” she said. So she started transcribing. The next step was instruments. “I discovered a Casio keyboard that I could set to play the entire C-major chord with drums and trombone with just one finger, so we had some of those. We had xylophones and recorders. Some people could learn a few chords on guitar. Whatever it was. But you put all that together, and it sounds darn good.”

And it’s kind of ironic, but Conroy, 61, has found that in teaching people with no musical background, she has drawn on “everything I ever learned in music school. If I didn’t have a super music theory background, I couldn’t be making these incredibly simple arrangements.”

The daughter of a psychoanalyst who had worked his way through college and med school tuning pianos, and film, stage, and TV actress Barbara Britton, Conroy grew up “surrounded by show people.” She got her Equity card at 7, performing in plays and occasional commercials with her mom. “I loved it,” she recalls, “but she didn’t want her kid to be a theater brat, so she didn’t let me do as much as I would have liked.”

The show-biz bug didn’t go away, though. When Conroy was 14, she recalls, “My parents were tootling me around to voice teachers, and one said, ‘Take her to Juilliard, and she’ll get the voice, the piano, and the theory all in one place.’” So Conroy auditioned for what is now called Pre-College. “It was the scariest day of my life. I knew from musical comedy and Peter, Paul, and Mary—but not classical music. They asked for English folk songs, but the only ones I knew were the child ballads that Joan Baez sang, so I typed up the information and handed it in, and the people behind the desk were saying to each other, ‘Do you know these songs? I don’t know these songs.’ And I felt like, Oh no! But I guess whatever they heard they figured I was worthy, so I studied with Ilse Sass [faculty 1964-69], who was adorable—so sweet.”

After studying voice at the University of Toronto, Conroy worked for the state theater of Heidelberg, Germany. “We had a ballet company, a theater company, and an opera company all under one roof. For me it was total delight. When I had a morning off, the ballet company let me do ballet barre. And sometimes singers were needed to do incidental music in the plays. It was a wonderful apprenticeship—I was on stage four to five nights a week; I learned to do my hair and makeup and just to be on stage. Had I been in a larger house, I wouldn’t have had that experience.”

Back home in New York a few years later, Conroy dusted off her Equity card (her father had been paying the dues), landed some dinner theater jobs and, before long, was soloing at Radio City Music Hall—as well as doing operettas and theater “and whatever to make a living.” The “crazy, crazy fun” of life in post-sexual revolution, pre-AIDS New York City arts world was the backdrop to her first novel, One Man’s Music (Black Lyon Music, 2008), the coming-of-age tale of a soprano trying to find love and establish a career. Conroy is hoping her second book, a historical novel called His Majesty’s Theater that’s set in London in 1903, will come out this year.

While she was freelancing anywhere and everywhere, Conroy’s long-term fascination with the Irish harp eventually led to what is now the bulk of her career. After buying—and teaching herself—the Celtic harp (22 strings, no accidentals), she became a regular on the wedding, Renaissance festival, and cocktail party circuits. “One Christmas, someone who’d heard me asked if I would play at a nursing home,” she said. “So I walked into this harshly lit linoleum room with 10 people drooping in wheelchairs. But when I started playing “Hark the Herald Angels Sing’ or whatever it was, suddenly these people are sitting up and smiling and signing—and that was the ta-da moment that slowly led to my becoming a music therapist.”

A quarter century later, “miraculous” is how Conroy describes the effect that music can have on people with dementia or who are comatose or who are developmentally delayed children. She frequently gets calls from people asking if they can audition for Showstoppers, Conroy said, “And I tell them, ‘No, you audition us: I need people who really, really love working with people. If you happen to be talented, I’ll be thrilled, and if you don’t have musical talent, I will use you anyway,’” she said. “My seniors live to perform. It’s a real win-win.”